ISABELLA OF CASTILE

BY THE SAME AUTHOR

Ghosts of Spain

Catherine of Aragon

ISABELLA OF CASTILE

Europes First Great Queen

Giles Tremlett

Bloomsbury Publishing

An imprint of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc

50 Bedford Square London WC1B 3DP UK

1385 Broadway New York NY 10018 USA

www.bloomsbury.com

BLOOMSBURY and the Diana logo are trademarks of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc

First published in Great Britain 2017

Giles Tremlett, 2017

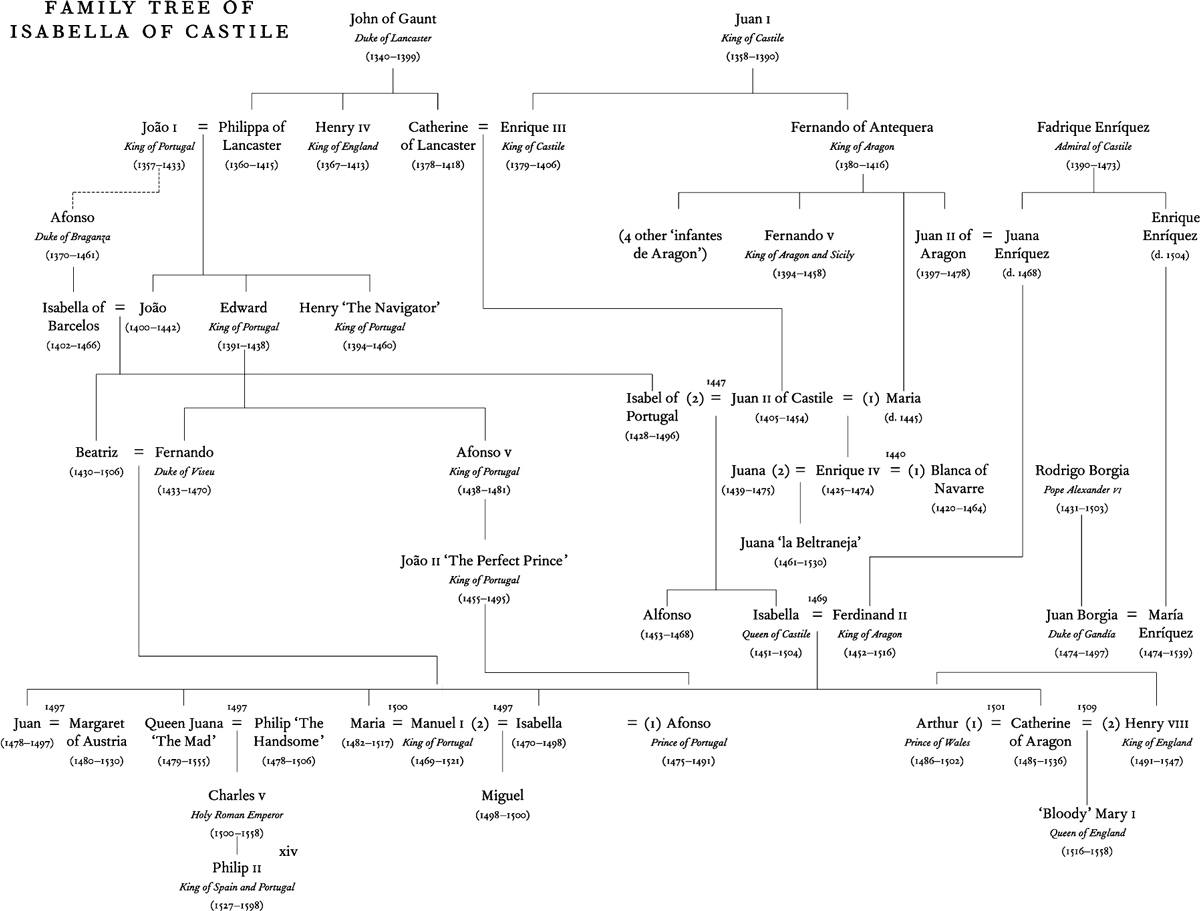

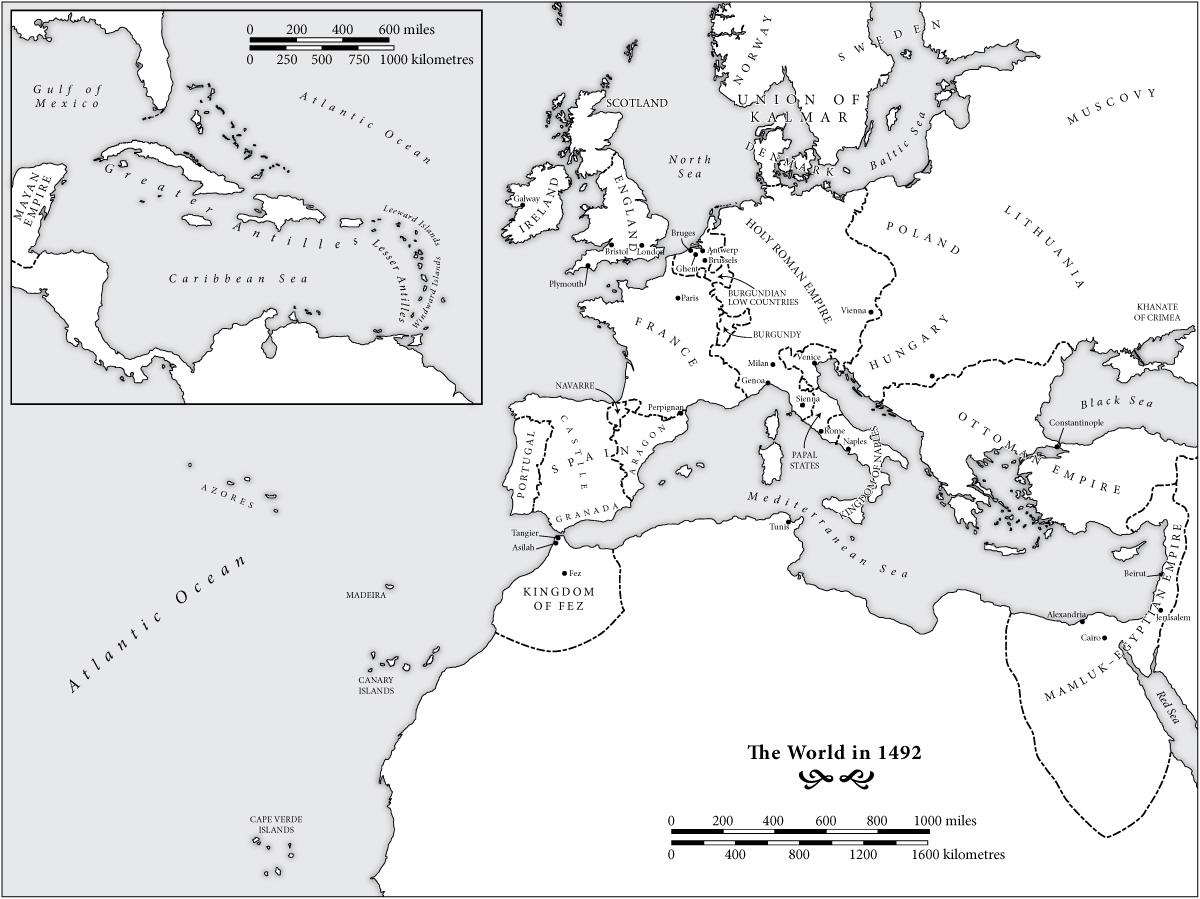

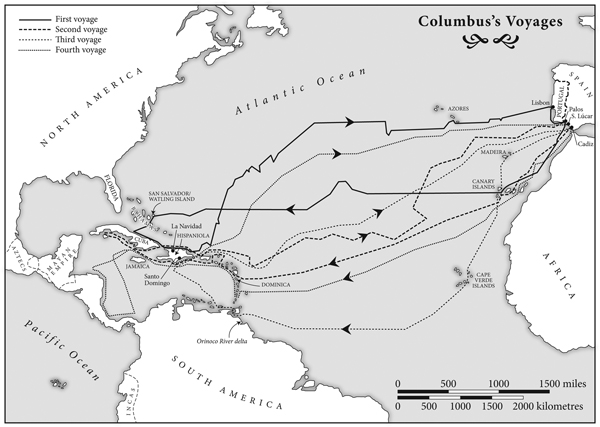

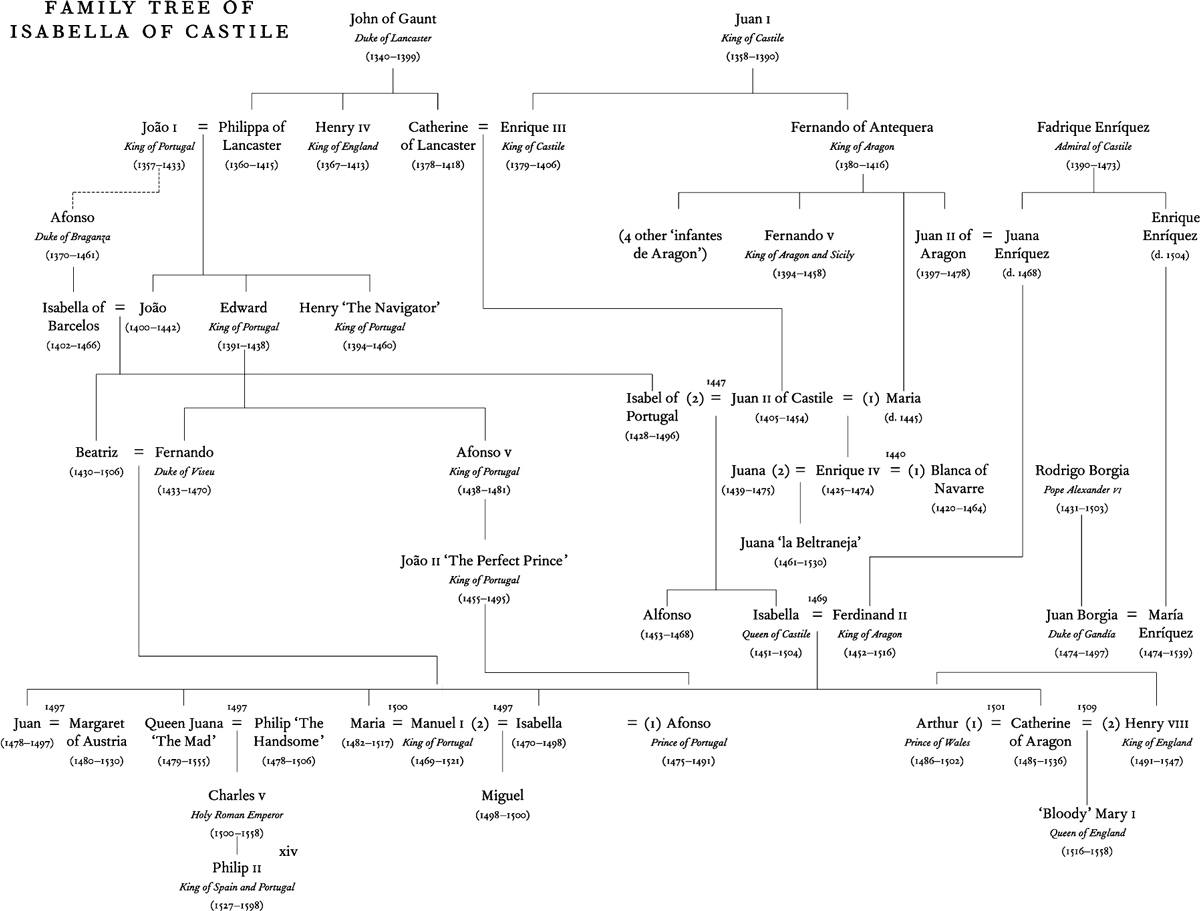

Map by ML Design. Family tree by Phillip Beresford.

Giles Tremlett has asserted his right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988, to be identified as the Author of this work.

Every reasonable effort has been made to trace copyright holders of material reproduced in this book, but if any have been inadvertently overlooked the publishers would be glad to hear from them. For legal purposes the Acknowledgements on constitute an extension of this copyright page.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publishers.

No responsibility for loss caused to any individual or organization acting on or refraining from action as a result of the material in this publication can be accepted by Bloomsbury or the author.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN: HB: 978-1-4088-5395-5

ePub: 978-1-4088-5396-2

To find out more about our authors and books visit www.bloomsbury.com. Here you will find extracts, author interviews, details of forthcoming events and the option to sign up for our newsletters.

No woman in history has exceeded her achievement.

Hugh Thomas, Rivers of Gold: The Rise of the Spanish Empire

Probably the most important person in our history.

Manuel Fernndez lvarez, Isabel la Catlica

To Katharine Blanca Scott, for all we have done and made.

CONTENTS

Segovia, 13 December 1474

The sight was shocking. Gutierre de Crdenas walked solemnly down the chilly, windswept streets of Segovia, the royal sword held firmly in front of him with its point towards the ground. Behind him came a new monarch, a twenty-three-year-old woman of short-to-middling height with light auburn hair and green-blue eyes whose air of authority was accentuated by the menace of Crdenass weapon. This was a symbol of royal power as potent as any crown or sceptre. Those who braved the thin, wintry air of Segovia to watch the procession knew that it signified the young womans determination to impart justice, and impose her will, through force. Isabella of Castiles glittering jewels spoke of regal magnificence, while Crdenass sword threatened violence. Both indicated power and a willingness to exercise it.

Onlookers were amazed. Isabellas

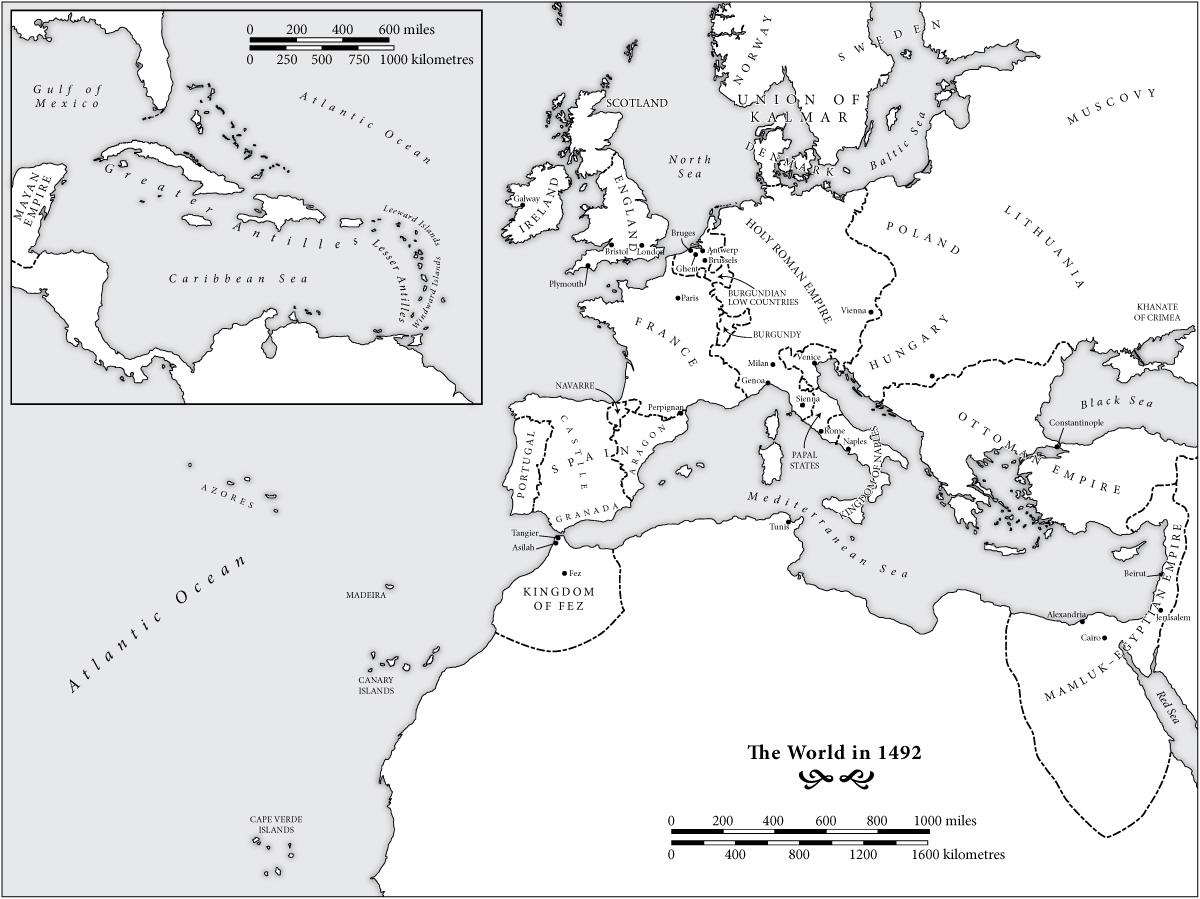

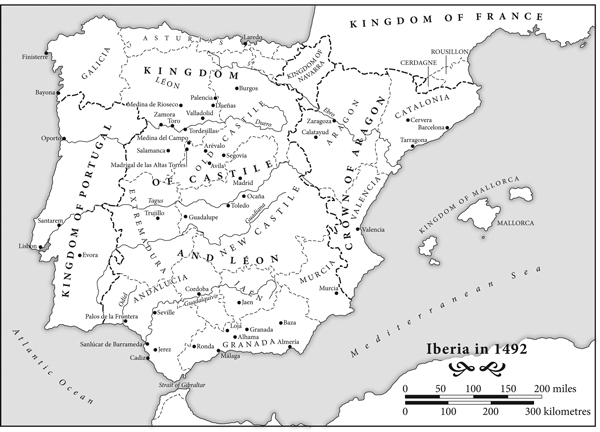

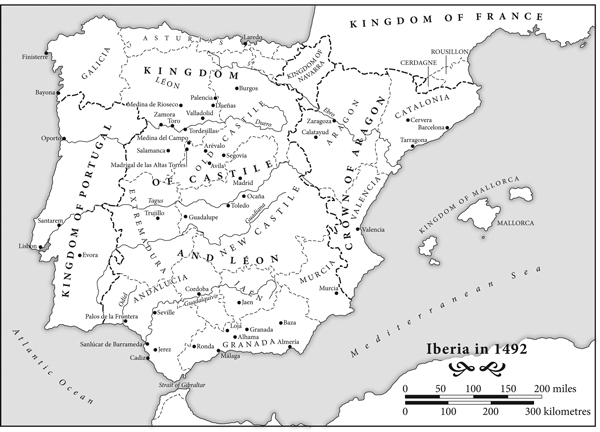

Castile was the largest, strongest and most populous kingdom in what the Romans (and their Visigoth heirs) had called Hispania and which today is divided between the two countries of the Iberian peninsula, Spain and Portugal. With upwards of4 million inhabitants it was significantly more populous thanEngland and one of the larger countries in western Europe. The kingdom that Isabella claimed was the result of a slow, six-centuries-long conquest of land occupied by the Muslims known to Christians as moros, or Moors who had crossed the nine miles of water that separate Spain from north Africa at the Strait of Gibraltar and swept through Iberia early in the eighth century. Castiles recent history of Lancaster, an English grandmother. To the north, France remained a far more potent power one that Castile was careful not to upset.

This author agrees, at least as far as female European monarchs and their impact on the world is concerned.

Isabellas achievements are not just remarkable because of her sex, merely more so. Isabella appeared after more than a century of crisis in Europe. In 1346, a force of besieging Tartars, they needed such a leader even more urgently.

Castilians hoped that the great saviour of Christianity would be one of their own monarchs, but weak kings brought constant disappointment. Foreigners saw squabbling Spain as shrouded in natural darkness, In Rome, the spiritual capital of Europe, the pope was only too aware of the importance of this wealth since Iberia provided a third of the papacys income.

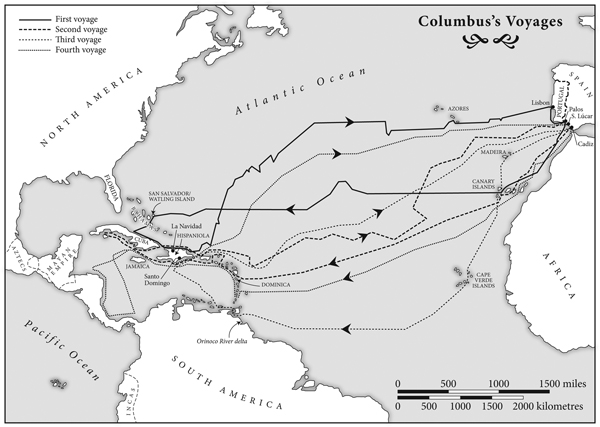

No one had ever imagined that the Last World Emperor would be a woman, but Isabella, in alliance with her husband King Ferdinand of Aragon, did more than any other monarch of her time to reverse Christendoms decline. Despite this, appreciation of Isabella has remained a largely Spanish thing. There are many reasons why. One is her use of violence. This is a legitimate and necessary tool for exercising power, but is often deemed disturbing when used by queens as if those who usurp the male role of leadership are driven by dark and vicious forces that annul a supposedly natural, gentle femininity. Isabella had no qualms about employing violence, feeling the hand of God behind every blow delivered in her name. Nowhere was this more so than in her attempt to finish off the so-called Reconquista by defeating the ancient Muslim kingdom of Granada. Isabella admired Joan of Arc, but made no attempt to imitate her by leading troops into battle. That was mans work, and she believed firmly in the division of the sexes (and classes, faiths and ethnic groups). In that, and many other things, she was not just a woman of her time, but a ferociously conservative one. Nor did she feel it necessary to feign any form of masculinity, though men often found they could explain her extraordinary success only by attributing to her some of their own, male qualities. Where Elizabeth I would later proclaim herself to have the heart and stomach of a king, Isabella preferred to express angry astonishment that as a weak woman she was so much more audacious and belligerent than the men who served her.

The Castile she claimed the right to rule owed its name to the castles, or castillos, that dotted a kingdom carved out over centuries of warfare and conquest of Muslim lands. Her countrys self-identity was shaped around its role as a crusading nation and defender of Christianitys southern frontier. The distinct regions of Castile owed their existence, too, to the different stages of a Reconquista which had started in the mountains that loomed over the Cantabrian coast in the north, and spread slowly into the wider area known as Old Castile. This lay north of a central chain of snow-capped mountains and sierras that included both the Guadarrama and Gredos ranges. Old Castile (together with the lands where the Reconquista was launched and had its first successes, in Asturias, the Basque country and Galicia) was fringed to the north and west by a wild, dangerous coastline. It included Spains own Lands End, or Finisterre, where wonderstruck Romans had come to marvel at the sun sinking below the western edge of the known world. This most ancient section of her realms was structured around a network of handsome, walled cities like Segovia, Avila, Burgos and Valladolid that had grown wealthy on the back of the wool trade. Every autumn the flocks of sheep traipsed south across the mountains or over the passes as Isabella herself put it to their winter pastures in the area that had become known as New Castile. This was presided over by ancient Toledo, with its magnificent churches, converted mosques and synagogues that jointly symbolised centuries of religious coexistence in Spain. Further to the south and west lay booming Andalusia, with its fertile plains, Atlantic ports and the countrys biggest city Seville as its thriving capital. Far off to the east lay the thinly populated frontier land of Murcia, which provided Castile with ports on the Mediterranean. Extremadura, on Castiles western border with Portugal, also owed much of its character to its own frontier status.

Next page