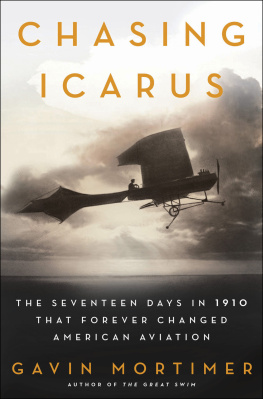

CHASING ICARUS

The Great Swim

CHASING

ICARUS

The Seventeen Days in 1910 That Forever

Changed American Aviation

GAVIN MORTIMER

Copyright 2009 by Gavin Mortimer

All rights reserved.

You may not copy, distribute, transmit, reproduce, or otherwise make available this publication (or any part of it) in any form, or by any means (including without limitation electronic, digital, optical, mechanical, photocopying, printing, recording, or otherwise), without the prior written permission of the publisher. Any person who does any unauthorized act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages. For information address Bloomsbury USA, 1385 Broadway, New York, NY 10018.

Published by Bloomsbury USA, New York

Bloomsbury is a trademark of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA HAS BEEN APPLIED FOR.

eISBN: 978-0-80271-960-7

First U.S. edition 2009

To find out more about our authors and books visit www.bloomsbury.com. Here you will find extracts, author interviews, details of forthcoming events and the option to sign up for our newsletters.

For Margot

CONTENTS

In the fall of 1910 no one could agree on what to call this daring new breed of men in the heavier-than-air flying machine. Aviators and fliers were the most popular (and prosaic) monikers, but journalists trawled their imaginations to come up with more colorful descriptions. Browsing through the newspapers on any given day, one might read of birdmen or man birds, dragon fliers or flierlings. Those reporters with a more lyrical bent opted for wizards of the sky or flying gladiators. Those less predisposed to melodrama simply called the men at the controls jockeys, riders, chauffeurs, or navigators of the upper regions. Just about the only word not deemed appropriate was pilot. Therefore, in keeping with the times, I refer to the men throughout the book either as fliers or aviators, and never as pilots. Similarly, aeroplane was as common as airplane, but for expediency I stick with the latter.

In addition, the International Aviation Cup, or the Coupe Internationale dAviation as the French called it, was sponsored by Gordon Bennett, publisher of the New York Herald newspaper. He also put his name to the International Balloon Cup. The trophies were often described by newspapers as the Gordon Bennett Aviation Cup and the Gordon Bennett Balloon Cup. To prevent confusion, I refer at all times to the International Aviation Cup and the International Balloon Cup.

The value of life lies not in the length of days, but in the use we make of them.

MICHEL DE MONTAIGNE, 1580

All of America was excited. The first Aviation Meet was about to take place on American soil, and the nations newspapers were in no doubt that a new chapter had begun. It was front-page news across the country on Sunday, January 9, 1910, from the Billings Daily Gazette to the Nevada State Journal to the Indianapolis Star. Monday in Los Angeles dawned with a clear blue sky and what one newspaper described as a mere zephyr of breeze that floated rather than blew up from the sea, and over the valley between the snow-capped mountains. Across the city thousands of people wolfed down their breakfast before riding the Pacific Electric trains fifteen miles south to what had once been called Dominguez Junction, but was now named Aviation Field. As they poured out of the cars onto the platform, children tugged at their fathers sleeves and asked what was that strange noise. Their fathers werent sure. Automobiles, most probably, belonging to the rich who had motored out from the city. To some dads, those who had fought in the Spanish-American War, the noise brought back memories of heavy machine guns in action.

None had ever before seen a heavier-than-air flying machine, and they had only read about them in newspaper articles illustrated not by photographs but by sketches of these newfangled inventions that seemed not much more than muslin, wood, and wire. In one such report, published in the Chicago Daily Tribune the previous fall, under the heading WHY AN AEROPLANE FLIES, the paper had explained to its readers, An understanding of what holds an airplane in the air can best be reached by going back to the old familiar kite. A kite is kept elevated by running with it against the wind, or by allowing the wind to blow against it. When the kite flies two forces work against each other; one, the force of the wind, the other, the weight of the kite. It is exactly the same with an airplane, with the exception that instead of waiting for the wind to blow against it, the airplane drives itself against the wind. This was done, continued the paper, by a propeller driven by a motor engine, which, for all the thrilling potential of the airplane, held the key to its development. If the propellers could whirl rapidly enough they could create an absolute vacuum in front and have thirty pounds per square inch on every inch of their back surface. If this condition were possible, or if engines powerful enough and propellers strong enough to withstand that pressure could be made, an aeroplane, according to such experts as the Wrights, could be sent through the air at a rate of 500 miles an hour. The principles of flight were lost on many among the crowd scurrying toward Aviation Field, but they didnt care. It wasnt the mechanics that mattered, it was the fact that man could fly. They all gasped when they saw the grandstand with its tiers of boxes already filling up quickly. It was fifty feet high and ran for seven hundred feet along one side of the field, its flags gently fluttering in the zephyr. On the opposite side were a row of giant white tents and a huddle of smaller tents at the far end of the field.

The crowd queued patiently to get onto the field, shuffling ever closer to the sign that hung at the entrance and boldly proclaimed in chalk letters a foot high THE BIGGEST EVENTS ARE YET TO COME. They handed over their $1 admission fee (approximately $16 today), clicked through the turnstiles, then rushed to seek out the best vantage points. Once they were happy with their spot, they sat on the grass and waited for the meet to start at one P.M. They shaded their eyes from the sun with their hands and looked toward the large tents, from inside which came the gentle whir of dirigible engines being tested. Farther down the field, nearly a mile away, were the smaller tents, and from inside came that strange noise again. The crowd could see men scurrying in and out of the tents, like rabbits in their warrens, and once or twice, just for a fleeting moment, they caught a glimpse of some strange contraption.

All through the morning Aviation Field filled with Americans come to witness with their own eyes the miracle of what some people called the heavier-than-air flying machine, and others the airplane. Between eleven oclock and noon three-car trains left the city every two minutes, and the thousands of people that they disgorged were corralled from the station to Aviation Field by three hundred deputy sheriffs, many of them on horseback.

Governor Gillett of California took his place in the grandstand, in among the elite of Californian society, who had arrived in the hundreds of automobiles that twinkled under the midday sun. The governor was publicly welcomed to the field by Dick Ferris, the master of ceremonies, who then declared the meet officially open. Few people in the crowd of fifty thousand were looking at Ferris as he spoke. Instead their attention was riveted on the monoplane that had been wheeled out from one of the tents onto the elliptical racetrack. A lean man, a mustache the only extravagance on a serious face, climbed up onto the seat. Ferris turned and introduced Americas own Glenn Curtiss, the greatest flier in the world, so he declared, who had gone to France the previous year and stunned Europe by winning the prestigious International Aviation Cup. The vast throng clapped and whistled, then rose to their feet in wonder as Curtisss airplane bounced along the racetrack and climbed slowly into the air. Around the racetrack flew the thirty-one-year-old, at a height nearly as great as the flags on top of the grandstand, before landing with a bump and a jolt twenty-eight seconds later. After a moments pause as the crowd struggled to absorb what they had seen, they shouted their approval. A watching reporter for Utahs