To my parents, Phil and Elaine

First published 2014

Amberley Publishing

The Hill, Stroud

Gloucestershire, GL5 4EP

www.amberley-books.com

Copyright Kathryn Warner, 2014

The right of Kathryn Warner to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyrights, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without the permission in writing from the Publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 9781445641201 (PRINT)

ISBN 9781445641324 (eBOOK)

Typeset by Fakenham Prepress Solutions, Fakenham, Norfolk NR21 8NN

Printed in the UK.

Contents

Acknowledgements

I am very grateful to Ian Mortimer, who suggested that I should write a biography of Edward in the first place, for his support, kindness and help over the years.

Thank you to Nicola Gale and everyone at Amberley.

Thank you to Susan Higginbotham for kindly providing me with helpful documents and for our many fascinating conversations about Edward.

Thank you to the staff of the National Archives, the Society of Antiquaries, Corpus Christi College Cambridge, Warwickshire County Record Office, Gloucester Cathedral, Berkeley Castle and Tewkesbury Abbey for their help.

Thank you to Folko Boermans, Sarah Butterfield, Lisa May Davidson, Jules Frusher, Vishnu Nair, Joe Oliver, Jennifer Parcell, Sami Parkkonen, Sharon Penman, Mary Pollock, Jamie Staley, Gillian Thomson and Kate Wingrove, for all your help.

Everyone who comments on my Edward site, all my history friends in real life and via email, on Facebook and Twitter, all over the world, unfortunately you are far too numerous to name individually, but I thank you all.

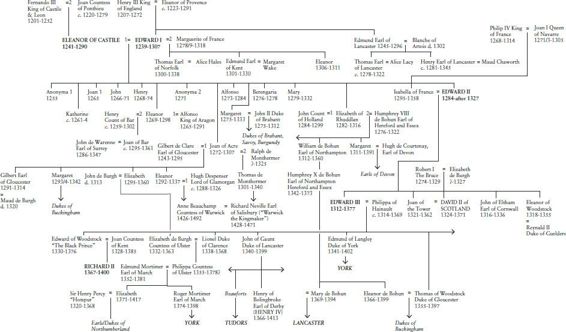

Foreword by Ian Mortimer

Primogeniture was a cruel method of selecting a king. The very idea that a man should be given absolute power simply on account of his paternity with no reference to his fathers or mothers qualities, or even his own ability seems a recipe for disaster. The added notion that his selection was a divine appointment made it impossible for him to refuse, even if he was exceedingly unsuited for political responsibility. At the same time, the dire penalties for failure meant that the throne cast a dark shadow across the consciences of its occupants. Even the most successful English kings had their daunting moments one thinks of Henry IIs war with his sons, the rebellions against Edward I in the 1290s, the parliamentary challenges to Edward III in 1341 and 1376, the attempts on Henry IVs life, and Edward IVs period of exile in the middle of his reign. All in all, it is surprising that so many English princes rose to the challenge of positive kingship: of the nineteen monarchs crowned between the Conquest and the Reformation, perhaps ten emerge with a reputation for successful leadership. As is well known, Edward II was not one of them.

Edward is rather a member of a more select group: a king whose failings were more important than his successes in the history of the realm. This does not make his reign any less significant than those of his predecessors; indeed, Englands great traditions of legal freedom and parliamentary representation owe far more to disastrous reigns than magnificent ones. We may look to William II, whose tyranny and accidental assassination paved the way for Henry Is charter of liberties the first time a king of England was formally bound to the law. There is the even more notable example of King John, without whose ineptitude there would have been no Magna Carta. The divisive rule of his son, Henry III, led to the establishment of the English parliament. And it was the reign of Edward II that brought to the fore the radical notion that Englishmen owed their loyalty to the Crown itself, not its wearer. Even more importantly, Edward IIs enforced abdication demonstrated that there were limits to the inviolable status of an anointed, hereditary monarch. From 1327, if a king of England broke his coronation oaths, he could be dethroned by his subjects acting in parliament.

There can be no doubt therefore that Edward II occupies a seminal place in the history of England and, indeed, of the whole of Europe. Moreover, it was not just his reign or a particular series of bad decisions that were important; it was his very personality that was the critical factor. When government was vested in a single individual, its failings were almost entirely personal. As Kathryn Warner makes clear in this book, Edward IIs short temper, his overbearing pride, and his refusal to compromise or make allowance for similarly brittle qualities in others, led to a violent clash with his most powerful cousin, Thomas of Lancaster, resulting in the latters downfall one of Edwards few triumphs. His personal vindictiveness towards Lancaster and his adherents led to many executions and accusations of tyranny, which ultimately led to Edwards own downfall. Trust Edward to snatch an utter calamity from the jaws of success! Overall, his internal battle to understand his own complex nature meant that he was always trying to have things both ways: to have the dignity and power of a king and yet at the same time the freedom of the common man to dig ditches, go swimming and give lavish gifts to his friends, if he felt like doing so. The result was the almost inevitable alienation of the nobility, who expected a man to be one thing or the other: either a properly regal king or a plain commoner. And Edward himself could not come to terms with their requirement for him to be both something he was and something he was not. Despite his piety, he was never truly able to resolve the great accident of his own birth that he, with all his faults and doubts in himself, had been chosen by God to be king.

A new biography of Edward II is thus an important publication. This is all the more the case as Edward II studies in the past have in many respects been lacking. Even at the sharper end of the historiography, academics adopted a sort of Edward II routine in which certain difficult questions were not asked, let alone answered in full. Nowhere is this more in evidence than with regard to his death the information underpinning which has been shown to be a deliberate lie, carefully designed to conceal the location of his new prison in late 1327. But it also applies to Edward as a man and thus to the entire understanding of precisely why his reign foundered. Scholarly medievalists who, in the twentieth century, favoured objectivity over a sympathetic portrait of the man, simply sat in judgement on him and did not seek to understand why he acted as he did. Thus they missed much of the mans character and failed to understand the reasons for his nobles actions. Only relatively recently with the publication of Seymour Phillipss Edward II has this generally parlous state of affairs been remedied but even that book demonstrates its authors inability completely to break away from the Edward II routine in respect of the mans death and possible later life.