Pagebreaks of the print version

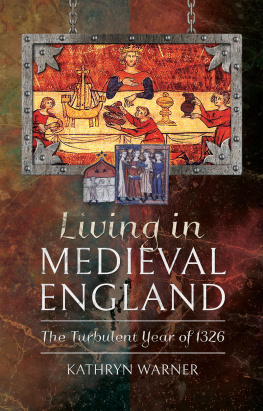

Living in Medieval England

Living in Medieval England

The Turbulent Year of 1326

Kathryn Warner

First published in Great Britain in 2020 by

Pen & Sword History

An imprint of

Pen & Sword Books Ltd

Yorkshire Philadelphia

Copyright Kathryn Warner 2020

ISBN 978 1 52675 405 9

eISBN 978 1 52675 406 6

Mobi ISBN 978 1 52675 407 3

The right of Kathryn Warner to be identified as Author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the Publisher in writing.

Pen & Sword Books Limited incorporates the imprints of Atlas, Archaeology, Aviation, Discovery, Family History, Fiction, History, Maritime, Military, Military Classics, Politics, Select, Transport, True Crime, Air World, Frontline Publishing, Leo Cooper, Remember When, Seaforth Publishing, The Praetorian Press, Wharncliffe Local History, Wharncliffe Transport, Wharncliffe True Crime and White Owl.

For a complete list of Pen & Sword titles please contact

PEN & SWORD BOOKS LIMITED

47 Church Street, Barnsley, South Yorkshire, S70 2AS, England

E-mail:

Website: www.pen-and-sword.co.uk

Or

PEN AND SWORD BOOKS

1950 Lawrence Rd, Havertown, PA 19083, USA

E-mail:

Website: www.penandswordbooks.com

Introduction

1326 was the year when the queen of England invaded her husbands kingdom with an army, grotesquely executed his powerful chamberlain who was perhaps also his lover, and brought about the forced abdication of a king for the first time in English history. It was also the year of the great drought, one of the hottest and driest summers of the English Middle Ages, and the year when the majority of English people carried on living their normal, ordinary lives: Eleyne Glaswreghte ran a successful glass-making business in London, Jack Cressing the master carpenter repaired the beams in a tower of Kenilworth Castle, Alis Coleman sold her best ale at a penny and a half per gallon in Byfleet, Wille Muleward made the king laugh when he spent time with him at a wedding in Marlborough, and the unfortunate John Toly died when he relieved himself out of the window of his London home during the night and lost his balance. Living in Medieval England: The Turbulent Year of 1326 tells the story of a country and its people throughout a single year, from January to December as per the modern calendar (in the fourteenth century, the new year began on 25 March, the feast of the Annunciation).

My main source has been the account book of Edward IIs chamber (one of the divisions of his enormous household), now kept in a library in London. I have long thought that this wonderful document, written daily in medieval French by the kings clerks, opens a window into England in 1326, and am delighted to have been able to make use of it as such. With a few exceptions I have not made generalisations about the era but have focused specifically on this one year, almost exclusively using sources which date from 1326. Although I have of necessity written much about King Edward and the invasion of his kingdom which his queen Isabella of France led, I wanted chiefly to shine a spotlight on the common people of England: the carpenters, the fishermen and fisherwomen, the shipwrights, the brewsters, the royal chamber valets, the archers, the carters, the wheelwrights, the sailors.

January

In the middle of the night between Tuesday, 31 December 1325 and Wednesday, 1 January 1326, an 80-year-old woman called Alis Pursere passed away a day and a half after falling down the stairs in her home in the London parish of St Mary Colechurch. Alis received the last rites before she died, and was survived by her husband Richard. In cases of death by misadventure, the value of the inanimate object which caused the accident had to be paid as a fine to the king and was called deodand , gift to God. The staircase down which Alis slipped was valued at 4 d by the jurors who investigated her death. A few hours after Aliss death and 75 miles away, two men called Richard Grene and Wauter Somery, who was known by the nickname Watte, approached the village of Haughley, 2 miles from Stowmarket in Suffolk. They were leading an expensive dapple-grey palfrey horse and carrying its saddle on a cart. The men had set off from the royal manor-house of Sheen on the River Thames west of London a few days before, and had now, after almost 90 miles, reached the end of their journey. John of Dunchurch (Warwickshire) and Thomas Wheler, known as Thomme or Tom in modern spelling, both carters, also approached Haughley on 1 January 1326. For the last three days, each man had driven a cart pulled by five horses and full of military equipment: a hundred aketons (padded jerkins often worn under armour), a hundred basinets (a kind of helmet), and a hundred pairs of gauntlets, all of which they were taking to the king.

Anneis May Anneis or Anneys was the fourteenth-century spelling of the name Agnes was already in the village of Haughley with her husband Roger. The couple came from the area of Lindsey in Lincolnshire, and their friends called them Annote and Hogge. Anneis was a talented seamstress who in January 1325 had stitched shirts for the two most powerful men in the country, the king and his chamberlain. On 1 January 1326, Anneis May received the wages of 7 s (84 d ) she was owed for the first twenty-eight days of her employment, and with her husband, worked in the kings couche chambre or bedchamber. Valet is a difficult word to translate and in the fourteenth century had many different meanings, but in this context basically meant a servant of low to middling rank.

King Edward was halfway through the nineteenth year of his reign, and was 41 years old. He spent the Feast of the Circumcision, 1 January 1326, in Haughley, and gave permission for two of his bondmen villeins or unfree tenants of the village, Thomas Wright and William son of Laurence of Hoo, to take holy orders.

The Suffolk village of Haughley belonged by right to the queen, Isabella of France ( c . 12951358), but the king had confiscated all his wifes lands in September 1324 after he went to war against her brother King Charles IV of France (r. 132228), and Haughley was presently in Edwards own hands. The palfrey horse brought to Edward in Haughley by Richard Grene and Watte Somery was a gift from his eldest and favourite niece Eleanor, Lady Despenser; it was the custom for the king to give and receive gifts on the Feast of the Circumcision. Eleanor sent letters to her uncle too, though her messenger who carried them to him, John Mot, arrived in Suffolk two days before Richard, Watte and the dapple-grey palfrey. Lady Despenser, born in October 1292 and now 33 years old, just eight years younger than her uncle, had married Hugh Despenser in May 1306 when she was 13 and he about 17. Twenty years later, Hugh was the kings chamberlain with responsibility for controlling access to Edward, and the man who had really been in charge of the English government for the previous few years.

Hugh Despenser was the son of the earl of Winchester (Hugh Despenser the Elder, born in 1261 and still alive in 1326), grandson of the late earl of Warwick and step-grandson of the late earl of Norfolk, a nobleman of high birth, and a pirate and an extortionist. He was present with Edward II in Suffolk at Christmas 1325 and the beginning of 1326. It is beyond doubt that the king loved Despenser and was highly dependent on him, and quite possible that the two men were lovers. The queen of England, Isabella of France, loathed and feared Hugh Despenser, and had sworn to destroy him. Edward refused to send Despenser away from court as Isabella demanded, and so the queen refused to return to England from her brother Charles IVs court in Paris, or to permit her and Edwards 13-year-old son Edward of Windsor, heir to the English throne and in her custody in her homeland, to return either. Such was the state of affairs in England at the start of 1326.