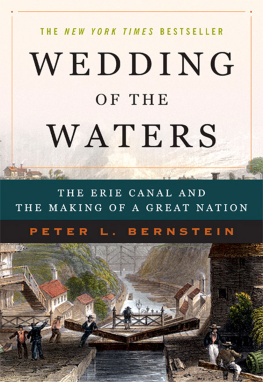

St. Martins Press

New York

Thank you for buying this St. Martins Press ebook.

To receive special offers, bonus content, and info on new releases and other great reads, sign up for our newsletters.

Or visit us online at us.macmillan.com/newslettersignup

For email updates on the author, click here.

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy .

The Erie Canal rubbed Aladdins lamp. America awoke, catching for the first time the wondrous vision of its own dimensions and power.

Francis Kimball

Upon my arrival in the United States, the religious aspect of the country was the first thing that struck my attention.

Alexis de Tocqueville

by Joy Taylor

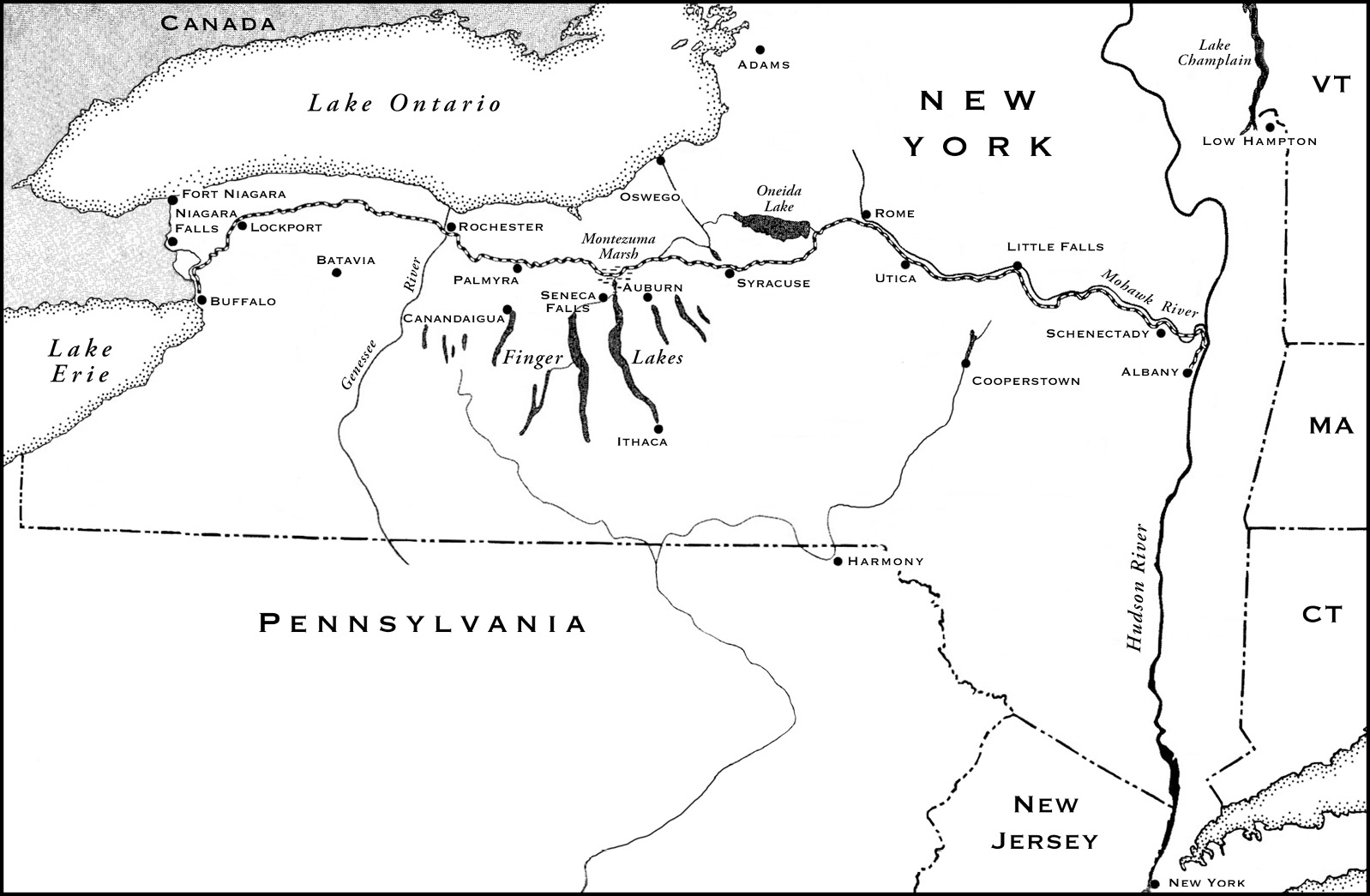

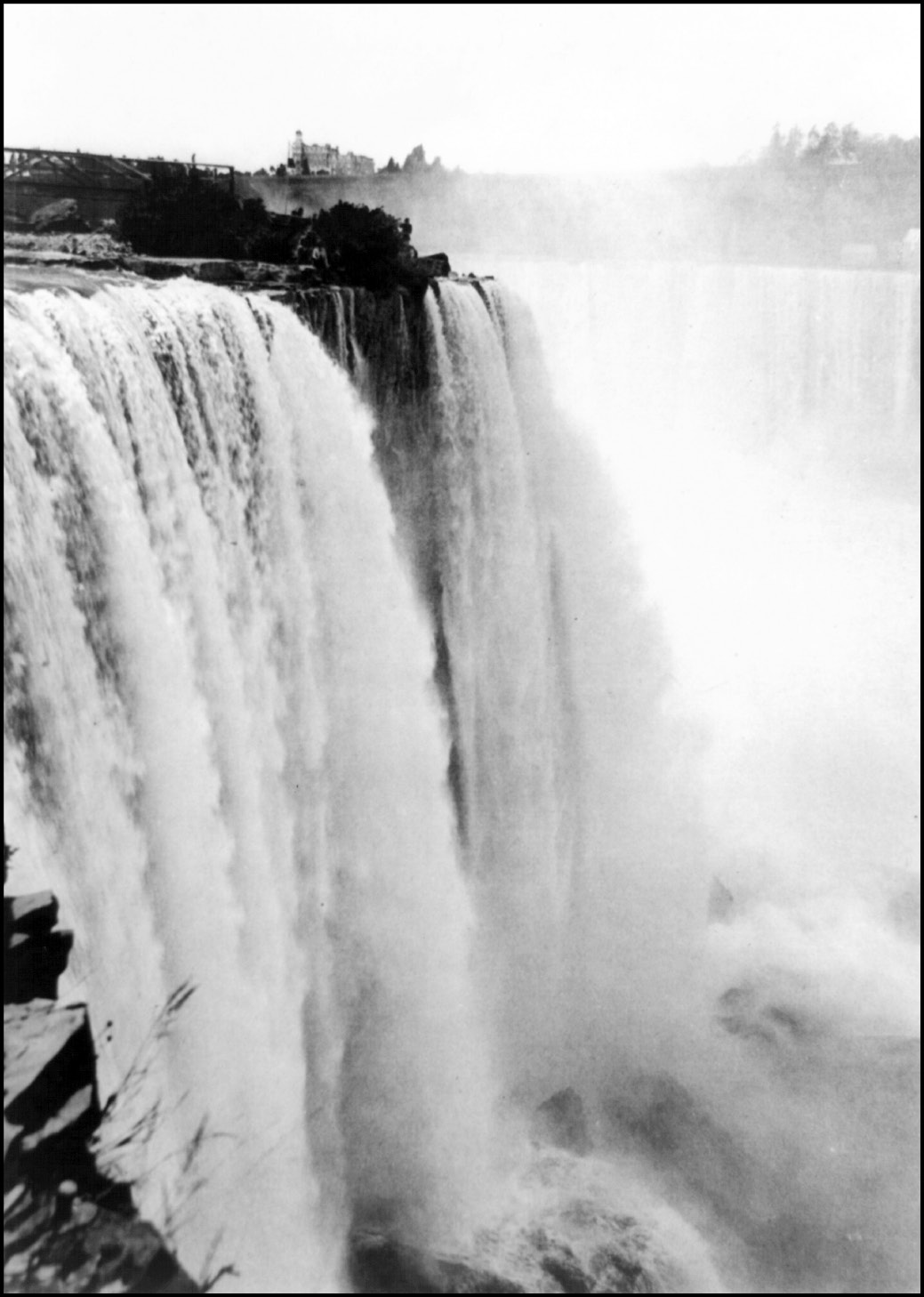

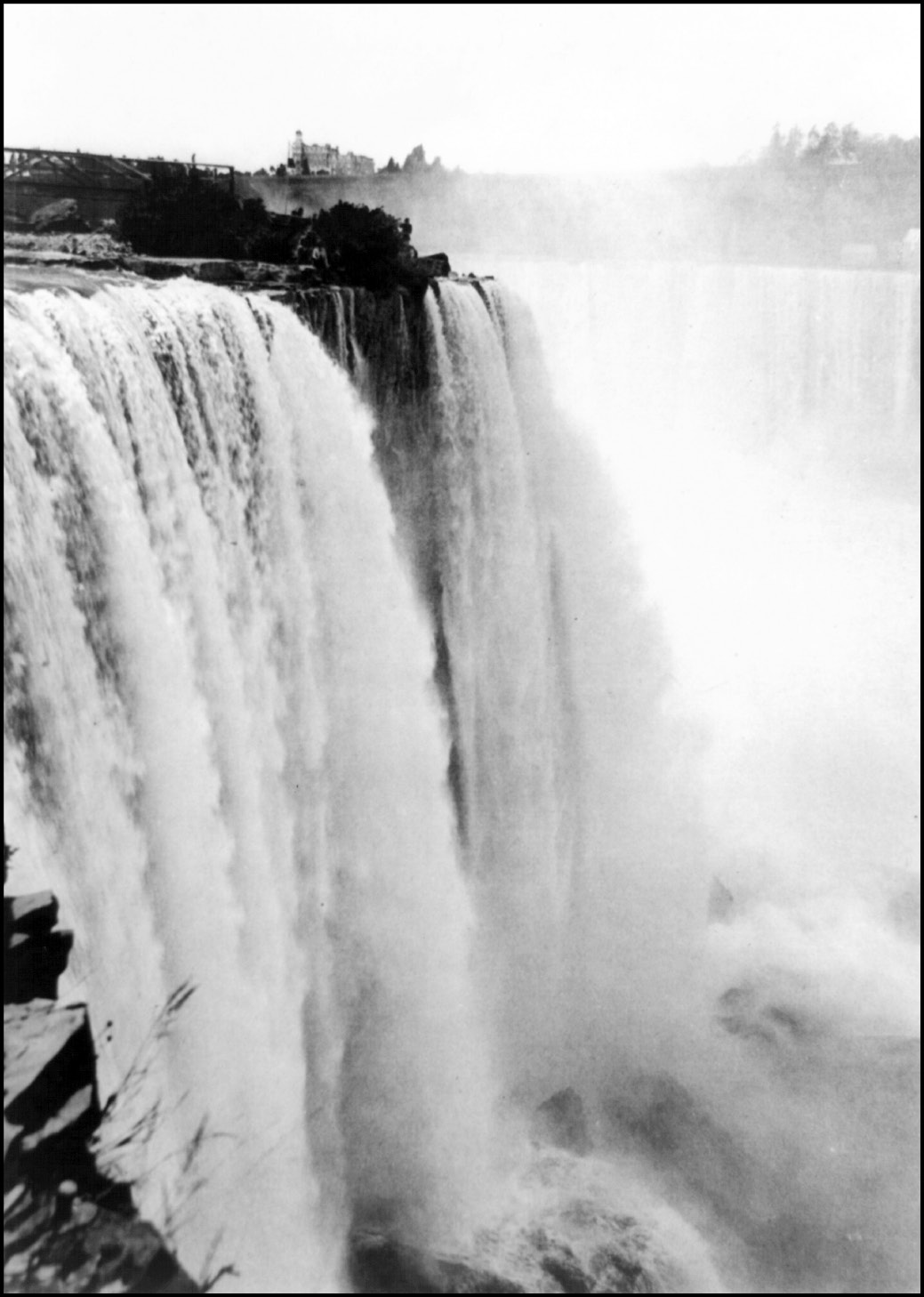

Jesse Hawley paced the office of a Seneca Falls miller. The room trembled as rushing water drove the mills cogwork. Amid the musty smell of grain, the curly-haired broker spread a map of New York State on a table and sat ruminating over it, forI cannot tell how long. His eyes lit on Niagara Falls. An image burst into his head. He saw the green water of the Great Lakes gushing in a mist-clad roar over that famous precipice. He imagined a great work of man diverting the flow into an artificial river, a canal running across the entire state. He saw a long parade of boats, each stacked with barrels of flour, floating down this channel toward eastern markets. To Hawley, a middleman in the western New York grain trade, it was a vision of wealth.

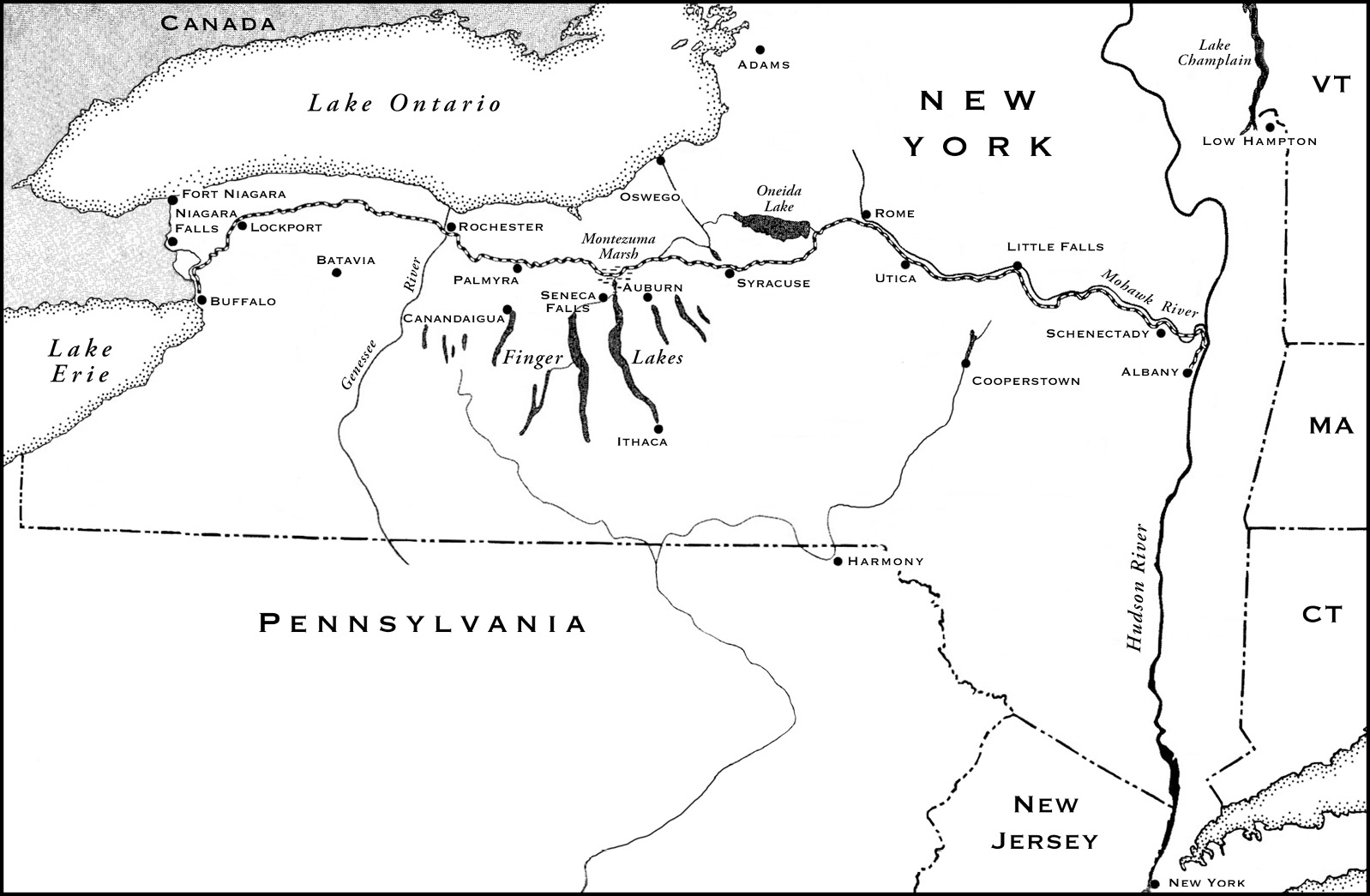

He had just been complaining to the mill owner about the states miserable transportation system. Farming in the Genesee country was productive, yes, but no one could make a profit manhandling heavy barrels along mud-clogged roads or transporting them down the unreliable, rapids-filled Mohawk River to reach the nations population centers. A canal was the answer.

Five years earlier, at the dawn of a new century, Hawley had joined the trickle of hopeful, daring Yankees who were heading west from New England, traveling beyond the wall of the Appalachian Mountains. Like most of them, Hawley was young, only twenty-seven then. Like many, he came in search of a fortune. Now, in 1805, he was facing bankruptcy.

Water was indispensable for carrying heavy loads. Teams of horses straining to pull wooden wagons could not compete with boats gliding along streams or lakes. Every major city in the nation had access to a river, a coast, or both. A horse that could move two tons along a smooth road could haul fifty tons down a canal.

Yet Hawleys idea was laughable. Three hundred sixty miles of tangled forests and dank swampland, of hills and valleys, separated Lake Erie from the Hudson River. Hawley needed only to consider the Middlesex Canal in Massachusetts, twenty-seven miles end to end. Then the longest canal in America, it had taken nine years to build. At the same rate of construction, a canal across New York State would not be completed until the unimaginable year 1925, when everyone now living would be dead.

To Hawley, geography represented both an obstacle and an intriguing promise. The Great Lakes, all but Lake Ontario, stretched halfway across the continent at the same elevation. The Hudson crept inland entirely at sea level. Link the two and you would join the distant west with the coast. The long downhill run from Lake Erie, dropping a foot every mile across the state to Albany, could carry a placid waterway navigable in both directions.

Visions are cheap; flashes of clarity come to us all. Translating a vision into reality is always the challenge. Hawley had little formal education and no training in canal design or construction. No one in North America knew much about the subject. Even the English expert who designed the Middlesex Canal was often at a loss when calculating levels or constructing locks.

Soon after the canal vision came to him, Hawley watched his business go bust. He fled the state to avoid debtors prison. Hiding out near Pittsburgh, he concluded, All my private prospects in life were blighted. To pass the time, he wrote two essays for a local newspaper on the subject of his dreamed-of canal. Determined to avoid ridicule and to hide his status as a deadbeat, he adopted the identity Hercules. I will presume to suggest, he began, the connecting of the waters of Lake Erie and those of the Mohawk and Hudson rivers by means of a canal.

The fugitives conscience soon got the better of him. He returned to the Finger Lakes settlement of Canandaigua to face the music: twenty months in debtors prison. Broken and destitute, he became convinced that hitherto I have lived with no useful purpose. To restore his sense of self-worth, he decided to publish to the world my favorite, fanciful project of an overland canal.

Hawleys prison was a Canandaigua hotel room. Confinement did not prevent his imagination from roaming freely. He managed to get hold of books and maps and to bone up on canal technology. Hercules wrote a series of fourteen essays published in the Genesee Messenger beginning in 1807. His choice of a route for the canal and his estimate of its cost were both remarkably prescient.

While he was writing, he learned of another transportation breakthrough. In August 1807, inventor Robert Fulton sailed the first commercial steamboat up the Hudson River, covering the distance from New York City to Albany in thirty-two hours instead of the four days needed by wind-driven schooners. Fulton became an instant celebrity and would soon sign on as an important canal backer.

All eyes were on the future. Hawley said it would be a burlesque on civilization to continue navigating farm brooks in bark canoes. Instead, he envisioned settlers rushing along canals to populate the newly accessible interior. He foresaw barges hauling flour, lumber and other produce from the Great Lakes down to the Hudson. Of New York City, he accurately predicted that in a century its island would be covered with the buildings and population of its city. Besotted with canals, he discussed waterways branching from his main Genesee Canal, and similar projects in other states. He even dreamed of a marine canal that would slice across the Isthmus of Darien, anticipating by a century the Panama Canal.

The reaction to the publication of his cherished idea was blunt. One critic declared that Hawleys scheme lies in the province of fancy, and may be treated as a vision. Another described it as the effusions of a maniac. President Thomas Jefferson judged the idea little short of madness. The future would render a different verdict.