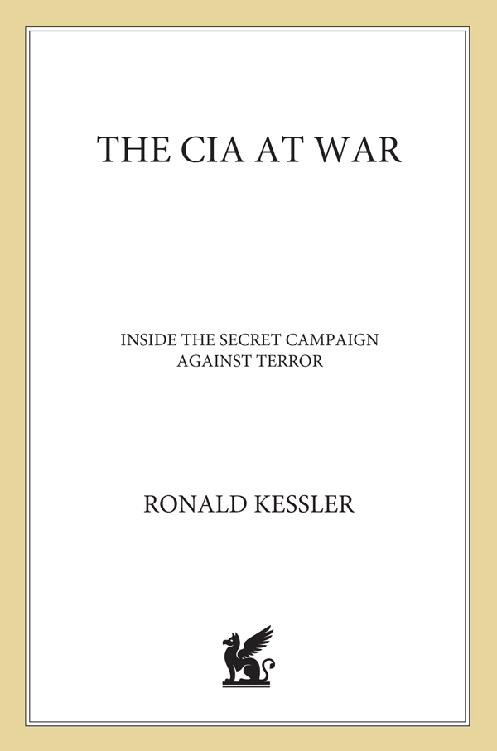

THE CIA AT WAR

INSIDE THE SECRET CAMPAIGN AGAINST TERROR

RONALD KESSLER

ST. MARTIN'S GRIFFIN  NEW YORK

NEW YORK

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: http://us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

For Pam, Greg, and Rachel Kessler and to the memory of my mother, Minuetta Kessler

At 8 A.M. on February 15, 2001, Mike, a trim-looking CIA analyst, gave President George W. Bush his first daily agency briefing at the White House. The next day, Bush would be making his first foreign trip as president, to see Mexican President Vicente Fox.

A White House steward entered the Oval Office with coffee. Bush motioned to his guest to stop talking while the steward was in the room. Mike was impressed. Bush cared about security.

At the end of the briefing, Bush brought up the trip again.

Are you coming with me? the president asked.

From that point on Mike or alternate CIA briefers traveled with Bush on every trip. They saw him six and often seven days a week, whether at Bush's ranch in Crawford, Texas, his parents home in Kennebunkport, at Camp David, or in the White House. The contrast with President Bill Clinton could not have been more striking. After the first six months of his presidency, Clinton dispensed with CIA briefings. He read only the President's Daily Brief, a compilation of intelligence reports prepared overnight by the CIA.

George H. W. Bush, a former director of Central Intelligence (DCI), had told his son after his election that the most important item of the day was the intelligence briefing. Meeting face-to-face with the DCI was also important, the former president said. When Bush chose Andrew H. Card Jr. as his chief of staff, he quoted his father's advice and said: Make sure that happens. I want to see the CIA director and talk with him.

Since the founding of the agency in 1947, no other president had wanted to be briefed by the CIA when he was out of town. Over time, no other president would come to rely so much on the CIA.

The first time Mike gave Bush a briefing was on January 4, 2001 at the president-elect's 1,600-acre ranch. Bush told him then what he expected from the CIA: There are people planning to do things that put U.S. security at risk, Bush said. They are trying to keep this secret. I expect the CIA to uncover those secrets and tell me. Second, I want the CIA to inform my decisions. I'll judge you on how well you do that.

Mike, in his forties, had been with the agency since 1980. During that time, he had helped produce the President's Daily Brief, which capsulized the CIA's hottest intelligence.

He gets it, Mike thought to himself.

More than two years later, on March 19, 2003, George J. Tenet, the director of Central Intelligence, told Bush that a CIA agent in Iraq knew that Saddam Hussein was in a bunker called Dora Farms. As Tenet briefed Bush, the agent called in more details on Hussein's movements. Based on that intelligence and the CIA's conclusion that Hussein continued to develop weapons of mass destruction, Bush ordered a strike on the compound and an invasion that obliterated Hussein's regime three weeks later. While the strike did not kill Saddam Hussein, the regime's command and control disintegrated after the blow.

We went right to the heart of their inner being, Tenet told me. Psychologically, that had to have a big effect.

Before Tenet became DCI in July 1997, the CIA was risk averse, awash in self-doubt, and mired in political correctness. After the attacks of September 11, 2001, Bush ordered Tenet to lead the war on terror. The agency would use its full complement of techniquesfrom human spying and interception of communications to satellite and reconnaissance plane surveillanceto find terrorists all over the world. In the war in Afghanistan, CIA paramilitary teams and U.S. Special Forces would hunt down terrorists and kill them. Now, not only was the agency in the forefront of confronting the gravest threat to the United States since the Soviet Union, its mission had changed. Besides warning of threats and pinpointing them, it had a license to kill.

Never in human history had a country relied so much on intelligence. Yet the question remained: Could the CIA be trusted? And even with its new powers, was the agency capable of winning the war on terror?

Because he is now undercover, Mike's last name is not used here.

A FTER JOHN M. Deutch resigned at the end of 1996, President Clinton nominated national security advisor Anthony Lake to succeed him. Lake withdrew his name after Republicans on the Senate Select Committee on Intelligence questioned his handling of personal stock transactions, his tough mindedness, and his politics.

Clinton then turned to George Tenet, forty-four. Also a Democrat, Tenet had been staff director of the Senate Select Committee on Intelligence, then became staff director for intelligence programs at the National Security Council (NSC). In July 1995 he was named deputy director of Central Intelligence, and in December 1996, acting CIA director. Finally, on July 11, 1997, Tenet became director of Central Intelligence, which placed him over both the CIA and the fractious American intelligence community. He was, as one CIA wag put it, the accidental DCI.

Traditionally, DCIs were WASPs with Ivy League backgrounds. Tenet's father John emigrated from Greece through France and Ellis Island just before the Depression. His name was Tenetis. When he entered France, immigration authorities listed his name as Tenet.

When he got to Ellis Island, he didn't speak English, so Tenet is what stuck, Tenet said.

Starting with nothing, John Tenet managed to save enough to open the 20th Century Diner in Queens, New York. George's mother Evangelia fled southern Albania, an area once part of Greece, to escape Communism. Somehow she persuaded the commander of a British submarine to take her out. She still spoke little English.

Tenet's first language was Greek, and the dinner table talk at home created an interest in foreign affairs. I don't think I woke up every day wondering if I was going to be James Bond, Tenet said.

Tenet attended the Georgetown University School of Foreign Service and obtained a master's degree from Columbia University's School of International Affairs. At age twenty-nine he joined the staff of Senator John Heinz of Pennsylvania, where he worked on national security and energy issues. In 1985, he became a staffer on the Senate Select Committee on Intelligence. Almost four years later, he became staff director, managing forty employees.

He could be forceful, said L. Britt Snider, who worked for Tenet on the committee and later became his special counsel at the CIA. He could come down on you. But he was always upfront, always played things straight.

Probably a hundred conversations he had with me started with his saying, You're not going to want to hear this, but , said Senator David L. Boren, who had been Tenet's rabbi, naming him staff director of the committee and recommending him to Clinton to head that president-elect's transition team on intelligence. Boren said, Sometimes he would start with, I can tell this isn't a good day to tell you this, and then he'd go ahead. His candor made him ideal for his future job of CIA director, Boren added.

NEW YORK

NEW YORK