Contents

Contents

Guide

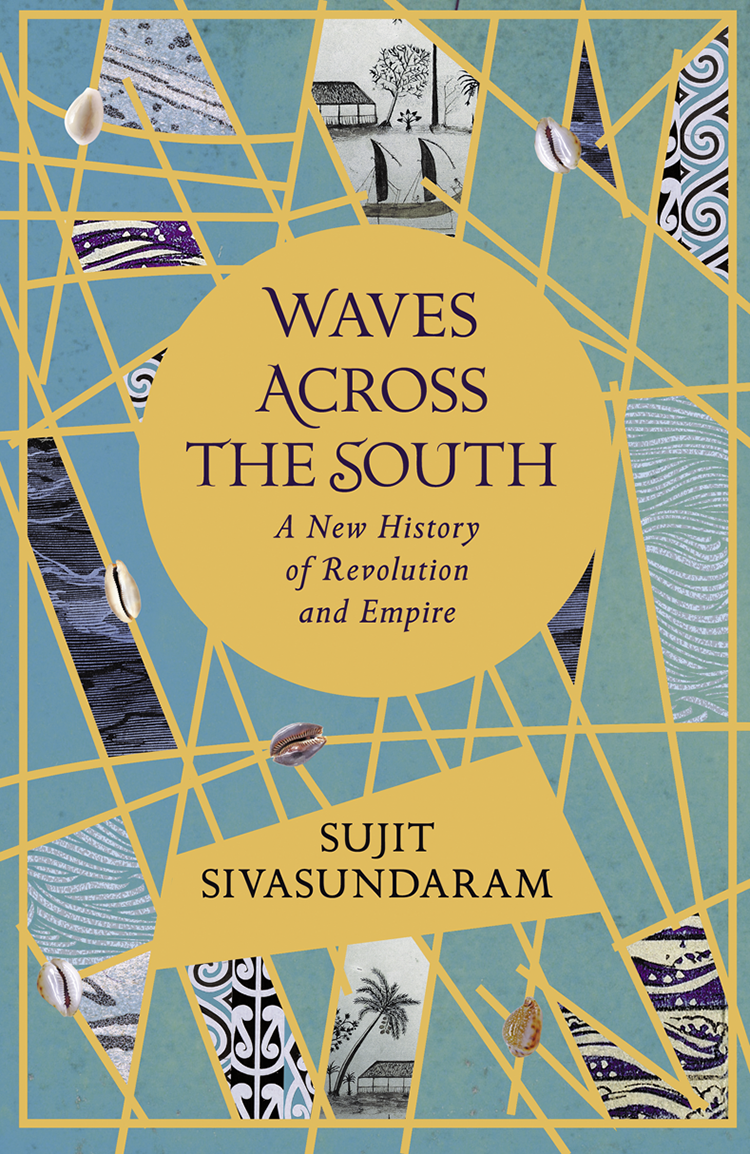

WAVES ACROSS THE SOUTH

A New History of Revolution and Empire

Sujit Sivasundaram

SUJIT SIVASUNDARAM is Professor of World History at the University of Cambridge and Fellow of Gonville and Caius College, Cambridge. He is the author of Islanded: Britain, Sri Lanka and the Bounds of an Indian Ocean Colony. He is a world-class historian specialising in the histories of the Pacific and Indian Oceans and their islands, the history of science, race, the environment and culture. This book arises out of his research in archives across the Indian and Pacific Oceans. This research was supported by the award of a Philip Leverhulme Prize for history, awarded to distinguished early career researchers in the UK.

THE SUN SWALLOWED BY THE WAVES

So much for words, their publication and their use to analyse the past. What about the waves? In this book, I have sought not to take the privileged view of the historian looking from on high, but to write from the small seas in the Indian and Pacific oceans.

As I write these words, I am in Port Louis in Mauritius and have just returned from swimming in the sea and watching the sun set after a day in the archives. Unlike Martin or Marryat, I didnt find myself imagining the setting sun moving to another part of the world, to illuminate another quarter and to keep day and night in predictable and never-ending imperial rhythm. The sun setting on the waters outside Port Louis, on this day at the end of the Mauritian winter in 2018, looks to me like the yolk of a fried egg. It is wondrously orange. The sun bloats and descends into the water and is swallowed in chunks by the waves out at sea. Mauritians tell me that the summers are getting hotter and hotter.

For a Sri Lankan used to big waves, swimming in the lagoon (the reef-calmed waters that stretch around a large part of Mauritius) is a surprisingly waveless experience. Today, in Port Louis Blue Penny Museum an exhibition on mid-nineteenth-century images of multi-coloured fish is under way. These brilliantly coloured fish seemed more alive to me than this still sea, even if their American artist, Nicholas Pike, froze his fish with their mouths open. In the reef, I cant see any fish. Port Louis residents say that the land is bleaching the sea and that fertiliser has entered the groundwater after centuries of heavy cultivation. Dead coral lies strewn on the beach. A young and clever Mauritian oceanographer explained to me that the public beaches, like the one I am now on, are too heavily used for coral or fish. The small number of public beaches is itself an indicator of the march of big tourist resorts on Mauritius coastline.

Along the public beach where Ive just swum, and right around Mauritius, are dozens of characteristic pirogues, historic wooden boats prized as a national treasure and used by local fishermen. One Ive just seen is named in big capitals: PIRATE. It makes me smile, a nice echo of Mauritius history which Ive charted. The landscape of Mauritius shows the afterlife of colonisation. Incredibly, about a quarter of Mauritius is still covered in fields of sugar. The Port Louis tourist trail includes the statue of Rmy Ollier in Jardins de la Compagnie, the garden at the centre of the city. Along the street named after Ollier I buy my Indian sweets and walk into Chinatown. I gaze enchanted at Jummah Mosque built at the point in Port Louis history where the last chapter ended.

The history of Waves Across the South has led into our present, and the signs of that past are still around us. It isnt the case that globalisation and imperialism have flattened islands and ocean-facing places, or the seas, into a universal equivalence. This is despite the dramatic political, environmental, social and cultural change enacted in sites like those covered in this book. Mauritius polyglot and energetic people are indicators of this. They include South Asians who speak creole at home and are fluent in French and South Asian languages. These South Asians first arrived in the island mostly as indentured workers and go on pilgrimage to Grand Bassin, where gigantic Hindu statues rise out of the Mauritian mountains. Even when indigenous people have faced tragic and fatal circumstances, including slavery, enforced labour, warfare and decimation, they have responded with ingenuity and ridden the waves. Outside Port Louiss municipal theatre, first built in 1822, I pause next to a plaque titled Universal Declaration of Human Rights: No one has the right to treat you as a slave nor should you make anyone a slave. But the islands Truth and Justice Commissions recommendations, which include the bid for a Slave Museum to memorialise this history of the island were halted for a long period. Meanwhile, as I write, historic buildings are being brazenly pulled down for a metro line.

To think of the dawn of the modern age as a contest of agents and ideologies human and non-human, indigenous and colonial, revolutionary and counter-revolutionary makes sense to an islander like me. To think like this contends with the violence of modern imperialism without letting it fill all the picture. It makes sense of the opportunities and foreclosures, the twists and turns of power. While writing this book Ive worked across the Indian and Pacific oceans, from Tonga to Aoteaora/New Zealand and from Burma/Myanmar to India and Singapore, from Australia to Tasmania, from the United Arab Emirates to Sri Lanka, Mauritius and South Africa. It has been an immense privilege and also a reminder that history looks so different when read from the ground, from the streets, the beaches, local bookshops, archives and libraries, and in the context of so many conversations with brilliant historians in each of these sites. The chapters of this book have also been written on site and the writing has flowed much better when Im here as in Mauritius rather than in my office at the University of Cambridge. Some of the stories in Waves Across the South have come as much from sniffing the ground and smelling the sea. They have also arisen from turning countless pages in archives such as that in Port Louis, set in an industrial estate, where drills and hammers or trucks unloading crates interrupt the experience of contending with the remains of the past.

But as I sit in the sand as the sun sets in Port Louis, allowing the drilling and banging to leave my head, with my feet in the ebbing sea, I start to worry again about the way the sea is changing. On another evening, I see the bright lights from the long line of ships on the dark horizon waiting to enter Port Louis harbour. One of the points of this book is that waves do not stop; revolution, empire and counter-revolt were part of a sequence of politics. Indigenous peoples continued to ride the waves despite the unprecedented onslaught of modern empire which sought to evacuate, bury and silence. But might it be that the constellation of waves, the connection and disconnection, the globalisation and imperialism, has now reached more and more interventionist and speedy concatenations in the twenty-first century?

Scientists theorise that wave heights are changing with global warming. If the seas creatures are dying just like the lands creatures, and if human actions are having a now unstoppable impact, what will this mean for the people of the Indian and Pacific oceans? Will our distinctive seas become more alike? I think back to the flatness of Tongatapu or how Beach Road in Singapore now lies far inland. Will the tsunamis become greater than the waves across the South that Ive been following? Will the pirogues, the catamarans, the dhows, and the double-rigger canoes, now need to contend with winds, waves and currents that they have never encountered before? Will the fear of being sunk in the tides of the modern, which was already evident in the period of this book and in this very language, become even greater in the years ahead? Will the scale of the infrastructural projects in the sea or of reclaiming land from the sea radically accelerate all this?