About 10,000 years before the birth of Christ , northern Europe was still covered by an ice cap. The weight of these immense glaciers - some as thick as 6,000 feet or more - caused much of the solid land to sink beneath the sea, only to rise again as the ice gradually melted; the region of Denmark was the first to become ice-free. In that distant past , what are now the Danish islands were a continuous land mass, joining Denmark to what was to become southern Sweden. As the land gradually rose - in Finland , it is still rising at the rate of approximately three feet each century - the sea came sweeping into the low ground, leaving the higher elevations as islands. There is evidence that man had penetrated to the coastal regions of the Arctic Ocean as early as 8000 B.C., but most of present-day Sweden, Norway, and Finland were still thinly peopled when tribes from southern Europe began to move into the region of Denmark in numbers about 2000 B.C. They were, like all the people of western Europe at this time, primitive hunting folk, using flint tools and weapons, and soon the venturers began to settle in Sweden also.

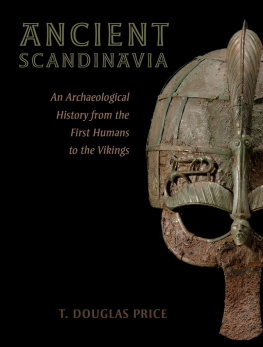

As the centuries passed, life became more civilized for these settlers, all of whom seem to have been of Germanic origins. A small Stone Age village which has been excavated at Alvastra, in Sweden, proves that its inhabitants sowed and harvested crops, domesticated cattle, pigs, and dogs, and were successful hunters and fishermen. Later, as mans knowledge advanced, and new waves of migratory peoples added their achievements to the accumulation of tribal skills, the Scandinavian peoples began to develop far-reaching trade. Especially important was the exchange of local goods for bronze, from as far away as Hungary, Spain, and France, and this Bronze Age lasted for about 1,200 years, until 600 B.C. Cliff drawings from this period that have been discovered in Sweden show that the ancestors of the Swedish people used oxen for plowing, traveled in horse-drawn carts, and went to sea in ships driven by oarsmen.

The Iron Age, which succeeded that of bronze, brought great advantages to Scandinavia, for Sweden had and still has vast quantities of iron ore. Once this could be smelted , it provided tools and weapons far better than any that had hitherto been possible. Little is known of the first part of this era, however, since the early Iron Age people seem to have preferred cremation to the burial rites of their forebears. (Bronze Age tomb furnishings give archaeologists their most useful clues to life in the period before history can be said to have really begun.) The Iron Age, which occupied the last five centuries before the birth of Christ, also seems to have brought to Denmark and southern Sweden bands of invading Celts, a more civilized central European people than the native inhabitants. These wanderers settled largely in Jutland, or the Cimbrian Peninsula as the Romans called it. A century before the birth of Christ , these Cimbri spilled out of Denmark across Europe and at last reached Italy, where they were beaten by the Roman general Marius at Vercellae in 101 B.C. No doubt the remnants of this raiding force fought their way back to Jutland against hostile tribesmen, and the Cimbri did not, for a while, again venture abroad. However, a return engagement with the Romans is mentioned by Emperor Augustus, who claimed in an inscription attributed to him, My fleet sailed from the mouth of the Rhine eastward to the country of the Cimbri, to which no Roman had ever penetrated before that time by sea or by land.... This is the first official reference to what we now know as Denmark.

In the meanwhile, on the eastern side of the Baltic, another group of nomads was establishing itself: T he Ugrians from the region of the Volga River were hunters, trappers, and fishermen. As they moved westward , the tribe split into two groups, one of which trekked toward the south and became the ancestors of todays Hungarians. The other group, keeping to the north, established themselves in what is now Finland and Estonia. In their advance into Finland , the Ugrian invaders settled among the Bronze Age people and drove north the native Lapps , who retreated toward the Arctic Circle, where they have lived as a separate and distinct group ever since. The Roman historian Tacitus wrote that these Laplanders were extremely wild, a reputation which their descendants have done something to maintain.

Meanwhile, the dark, inhospitable coast of Norway had also become thinly colonized by western and central European immigrants who had come by way of Denmark, Sweden, and Russia. By the eighth century A.D. , these settlers had found that their new, thickly forested homeland was altogether too bleak and unfertile for their tastes, which with the stimulation of developing trade and international communication had become more demanding.

Geography determined the direction in which the Northmen now struck. The land route toward the south was blocked in the ninth century by the great Frankish empire of Charlemagne and by the warlike Saxons; eastward and westward, however, the coast was, literally, clear. The Danes, closer to the English Channel than the Norwegians, attacked Frisia (corresponding roughly to the Netherlands), southern England, and France; the Norwegians swept out toward the Orkney and Shetland islands, the Isle of Man, Ireland, Scotland, and Northumbria; and the Swedes went east. The Finns enjoyed the benefits of Swedish commerce with the East but did not themselves launch any raids except upon the Lapps.

The term Vikings had been loosely applied to all these sea raiders, whether Danish, Swedish, or Norwegian, and it derives from the word vik which still means creek in all Scandinavian languages. The Vikings were creekmen . Their longships lay hidden in creeks and bays, ready to swoop out against any passing vessel, and they used the waterways to penetrate the countryside which they intended to plunder.

Norsemen is simply an alternative name for these marauders, again applied to all three Scandinavian peoples. Normandy, settled by the Danes in 911, reminds us of the Norse origins of that duchy and to this day Norwegians refer to themselves as Nordmenn . (The Norse invaders of Russia are alternately known as Varangians, derived from an old Norse word, possibly meaning confederate, and Ruotsi , meaning the rowing men in old Finnish.)

With the passage of time , the raids were organized on a large scale until at last they became colonizing expeditions, carefully planned and skillfully executed. Because of their riches, English and Irish monasteries were always a prime target for the Vikings, and the people of the villages which clustered around the great religious houses learned to look fearfully toward the sea whence came, in the words of a monkish chronicler, great armies of Norsemen like storm-clouds or swarms of grasshoppers. As the historian Adam of Bremen wrote of the Vikings in the tenth century, Forced by the poverty of their homeland they venture far into the world to bring back from their raids the goods which other countries so plentifully produce. Northern France and Iceland also learned to dread them.

The Vikings were democrats, in a sense. Great fleets of hundreds of longships were assembled for a large expedition without any single leader being in charge of the operation. We are all equals, said the Norsemen proudly to the envoy of the king of France who came to Normandy inquiring for their leader, and there was some truth in this. Women were held in highest esteem by the Vikings and enjoyed rights of property and status which their sex was not to enjoy elsewhere until many centuries later.

What is known of the legal proceedings of Iceland during the Viking era is probably true in a general sense of the government of all the Nordic peoples. Laws derived from the decisions of the