CAMPAIGN 203

TRENTON AND PRINCETON 177677

Washington crosses the Delaware

| DAVID BONK | ILLUSTRATED BY GRAHAM TURNER |

| Series editors Marcus Cowper and Nikolai Bogdanovic |

CONTENTS

The Spirit of 76 This 19th-century illustration is an idealized view of the citizen soldiers who sustained the American Army through the dark period of Washingtons retreat through New Jersey.

ORIGINS OF THE CAMPAIGN

With the fall of Fort Washington on November 16, 1776, the cause of American independence appeared to teeter on the brink of failure. American fortunes never seemed brighter than after the British evacuation of Boston in March 1776. Although there was jubilation at the British retreat American commander-in-chief General George Washington knew the British would be back. Even as the British were preparing to sail from Boston Washington had ordered men and matriel shifted south to New York. As early as January Washington had dispatched Major-General Charles Lee to assume command of the city and prepare its defenses.

The heady days of spring quickly turned sullen in June 1776 when the British fleet arrived off New York and General William Howes British Army established themselves on Long Island. As summer turned to fall Washington and his army suffered a series of demoralizing defeats. While the Americans avoided catastrophic defeat, Washington was outmaneuvered and outgeneraled and his army was driven out of New York. Unsure of Howes intentions Washington consulted his senior officers and decided on November 6, 1776, to divide the army into four distinct commands. The largest force, 7,000 men under Maj. Gen. Charles Lee, was assigned the task of blocking any British move north into New England. Major-General William Heath was given 4,000 men and assigned the objective of defending the Hudson Highlands at Peekskill, New York. Washington retained about 2,000 men to defend New Jersey and to support Major-General Nathaniel Greene, who was given command of the strategic forts Washington and Lee along the Hudson River.

The Americans began their movements on November 7 and Washington left White Plains on November 10, reaching Fort Lee to confer with Major-General Greene on November 13. To defend the two forts Greene had over 5,000 men under his command. Greene assured Washington that Fort Washington could hold out for several days and if forced to retreat the garrison could safely cross the Hudson River. Although Washington had recognized the vulnerability of Fort Washington and been disposed to abandon it, Maj. Gen. Greene had convinced him that its defenses were strong enough to delay the British long enough to allow for an orderly withdrawal. Against his own judgment Washington accepted Greenes argument.

The British attack on Fort Washington began early on November 16 and by 4.00pm over 2,800 American defenders had surrendered. General Washington watched helplessly in growing despair and disillusionment from across the Hudson River at Fort Lee.

Although Washington took no action against Greene, who had shown organizational talents in arguing for the establishment of a series of supply points across New Jersey in the event of a retreat, his confidence had been shaken. Washington noted that Maj. Gen. Greene had erred in his judgment in believing Fort Washington could be defended. Confidence in Washingtons leadership had already begun to erode as the American Army was pushed out of New York. The loss of Fort Washington gave further evidence to his critics that Howe had outgeneraled him.

With the losses in manpower from the battles around New York, the recent surrender of over 2,800 at Fort Washington and the deployment of another 2,000 men at Fort Lee, Washington was left with the poorly trained and equipped units of the Flying Camp. These were militia units raised by Congress in June 1776 from Maryland, Delaware and Pennsylvania intended to act as a mobile reserve and defend New Jersey from invasion. Their enlistments were scheduled to expire on December 1 or December 30. They included Brigadier-General Nathaniel Heards New Jersey Militia, Brigadier-General Reazin Bealls New Jersey Militia and Pennsylvania Militia under the command of Brigadier-General James Ewing.

Washington realized the loss of Fort Washington rendered Fort Lee untenable to defend and dangerous for the troops garrisoned there. He ordered Greene to begin the process of withdrawing the defenders and the large quantity of supplies to the relative safety of the interior of New Jersey. Greene wrote to Washington on November 18 that he had begun to remove the supplies. Greene reported that he did not trust the powder and ammunition to water transport and was struggling to find enough wagons to carry away the supplies. Given Gen. Howes ponderous style of pursuit the slow pace of the removal of supplies did not appear to raise serious concerns.

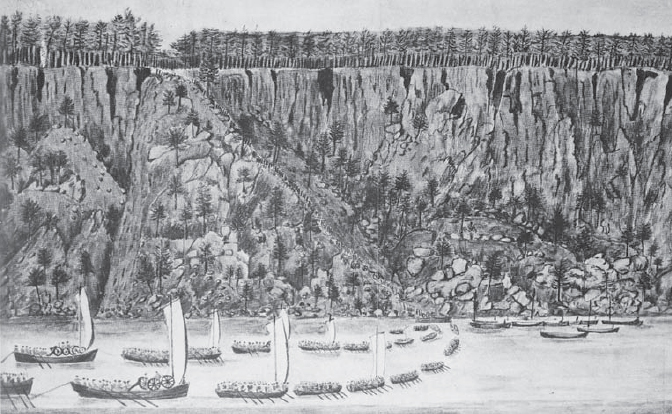

Late on the night of November 19 British and Hessian troops under Lieutenant-General Charles Earl Cornwallis crossed the Hudson River several miles north of the fort at Lower Cloister Landing, New Jersey, and under cover of a cold rain and damp mist climbed the Palisades, a range of steep bluffs along the Hudson. American patrols had been stationed along the Palisades but the Lower Cloister Landing, at the foot of the Palisades, was considered an unlikely crossing point.

The British and Hessian troops climbed a narrow four-foot path to the crest, dragging their artillery behind. Cornwalliss taskforce, numbering 5,000 men, included British light infantry and Hessian Jger, British and Hessian grenadiers, British guards, Highlanders of the Black Watch, the British 33rd Regiment and the Queens American Rangers. The combined British and Hessian troops, arriving in two waves, began disembarking at 8.00am and by 10.00am the entire force was ashore. By the time the infantry climbed the narrow path and the artillery was manhandled to the top of the bluff it was after 1.00pm. Although Fort Lee lay only five-and-a-half miles directly to the south the distance by road was closer to 10 miles and the main British force did not begin its march until mid-afternoon.

Washington received word of the British attack at 10.00am at his headquarters in the Zabriskie Mansion at Hackensack, New Jersey, five miles from Fort Lee. Washington sent orders to Maj. Gen. Nathaniel Greene, commanding the Fort Lee garrison, to retreat immediately and then directed American troops to secure the village crossroads at Liberty Pole and the New Bridge across the Hackensack River. New Bridge was approximately four miles north of Hackensack and about seven miles from Fort Lee. The Liberty Pole crossroads was located between New Bridge and the fort.

British landing at Lower Cloister Landing, November 20, 1776. The British chose the Lower Cloister Landing because of the difficult approach to the tops of the bluffs. Cornwallis guessed correctly that the Americans would not guard this landing point.

Washington and several aides crossed the Hackensack River and rode to meet the retreating garrison. Washington, still concerned about a possible British move toward Liberty Pole, only two miles from the British assembly point, decided to remain at the crossroads and wait for the retreating garrison. Possession of both Liberty Pole and New Bridge were critical to covering the retreat of the Fort Lee troops. If the British captured either position they would cut off the retreat of the Fort Lee garrison. Washington also ordered one aide to return to Hackensack and send an immediate note to Maj. Gen. Lee, detailing the rapidly developing situation and directing him to cross the Hudson River according to previously agreed plans. The message noted that detachments of the enemy were only two miles north of Liberty Pole.

Next page