Contents

Guide

ALSO BY JENNET CONANT

Tuxedo Park: A Wall Street Tycoon and the Secret Palace of Science

That Changed the Course of World War II

109 East Palace: Robert Oppenheimer and the Secret City of Los Alamos

The Irregulars: Roald Dahl and the British Spy Ring

in Wartime Washington

A Covert Affair: Julia and Paul Child in the OSS

Man of the Hour: James B. Conant, Warrior Scientist

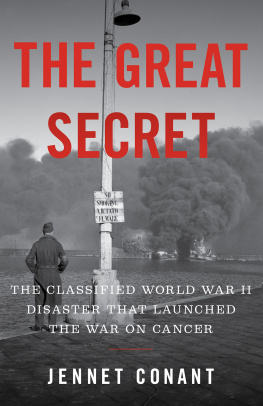

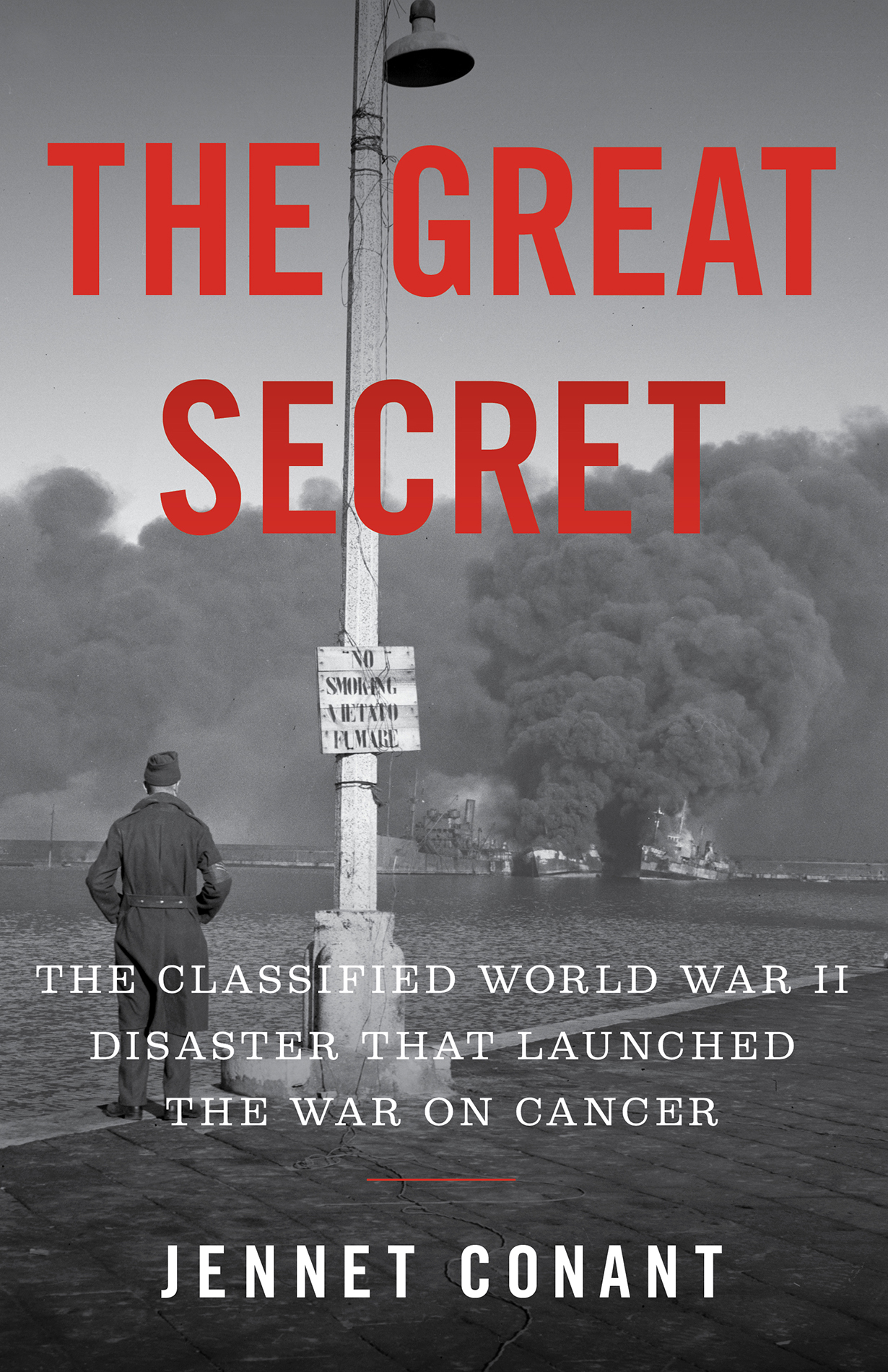

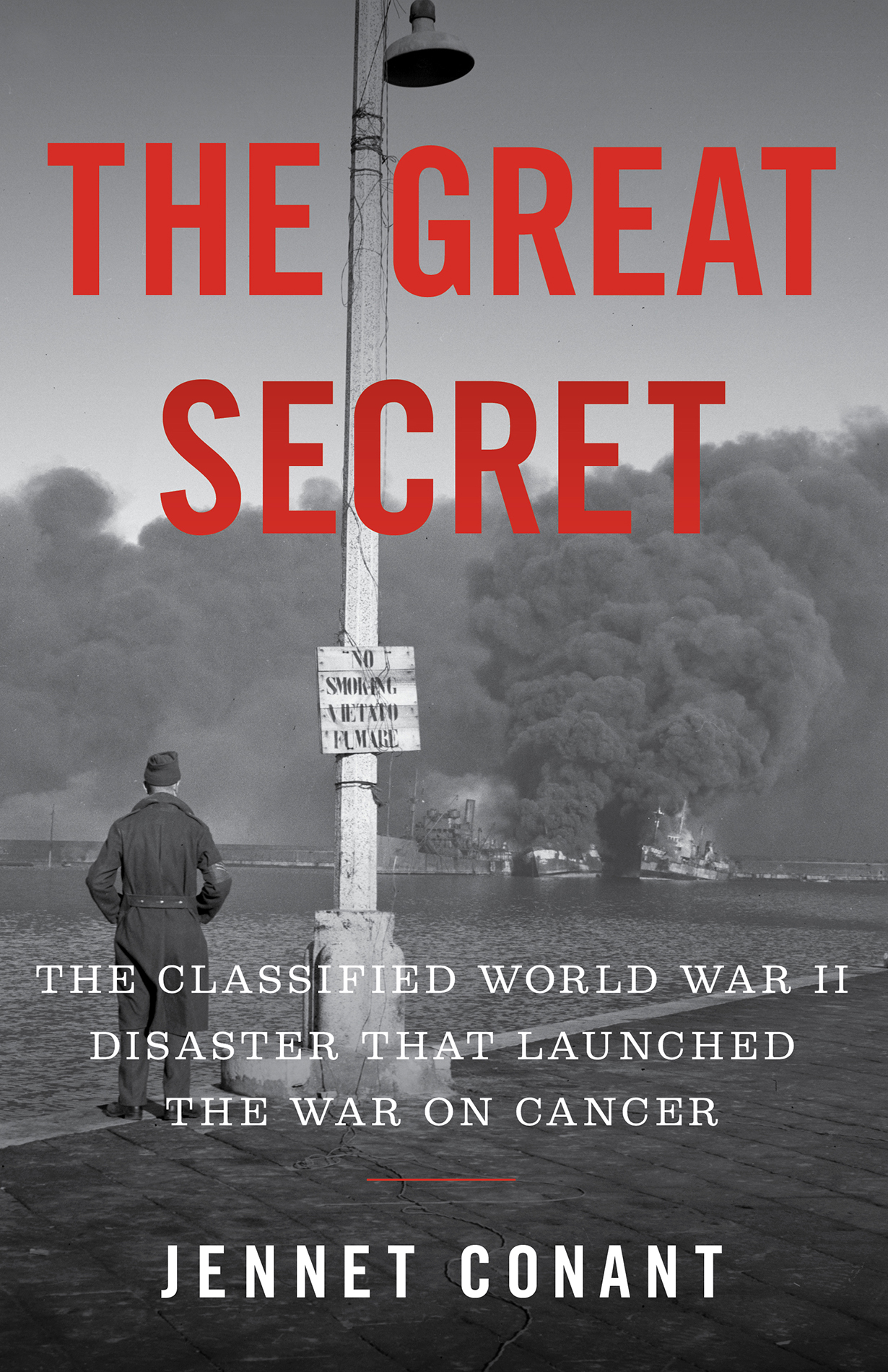

THE

GREAT SECRET

THE CLASSIFIED

WORLD WAR II DISASTER THAT

LAUNCHED THE WAR ON CANCER

JENNET CONANT

Copyright 2020 by Jennet Conant

All rights reserved

First Edition

For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book, write to Permissions, W. W. Norton & Company, Inc., 500 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10110

For information about special discounts for bulk purchases, please contact W. W. Norton Special Sales at specialsales@wwnorton.com or 800-233-4830

Jacket design by Jarrod Taylor

Jacket photograph: National Archives (111-SC-186573)

Book design by Michelle McMillian

Production manager: Beth Steidle

The Library of Congress has cataloged the printed edition as follows:

Names: Conant, Jennet, author.

Title: The great secret : the classified World War II disaster that

launched the war on cancer / Jennet Conant.

Description: First edition. | New York : W. W. Norton & Company, 2020. |

Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2020016332 | ISBN 9781324002505 (hardcover) | ISBN

9781324002512 (epub)

Subjects: LCSH: Chemotherapy. | CancerTreatment. | CancerResearch. |

Mustard gasToxicology.

Classification: LCC RM260 .C63 2020 | DDC 615.5/8dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020016332

W. W. Norton & Company, Inc., 500 Fifth Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10110

www.wwnorton.com

W. W. Norton & Company Ltd., 15 Carlisle Street, London W1D 3BS

In wartime, truth is so precious that she should

always be attended by a bodyguard of lies.

WINSTON CHURCHILL

The real war will never get in the books.

WALT WHITMAN

Contents

PROLOGUE

Little Pearl Harbor

W hen the two Time-Life war correspondents arrived in the old port town of Bari on Italys Adriatic coast on Thursday, December 2, 1943, they were delighted to find the bars and restaurants open and doing a booming business. Will Lang, a twenty-nine-year-old veteran American combat reporter, and George Rodger, a trailblazing English photojournalist six years his senior, grabbed the first empty table in the Albergo Oriente, a glass-fronted hotel on a wide, tree-lined boulevard in the new part of the city. Exhausted, they collapsed onto the rickety chairs and grinned at each other. By some stroke of luck, they had a two-day layover and planned to take a little break and overindulge in the local wines before returning to the grind.

Even though the front lay only 150 miles to the north, Bari seemed not to have a care in the world. The British had taken the capital of Puglia unopposed in September, and the citizens had celebrated in the streets, relieved and grateful to fall under Allied protection. The shop windows were full of fruit, cakes, and bread, along with other delicacies not seen since before the war. Waiting customers happily gossiped, argued, and haggled. Young couples strolled arm in arm, as they had for centuries. Even the ice cream vendors were doing a brisk winter trade, an incongruous sight for the journalists after having passed lines of women and children begging for black-market food only a few miles outside of town. After witnessing the chaos and misery in one village after another flattened by German bombs, the men were amazed that the medieval city, with its massive cliffs cradling the sea, had escaped the fighting almost unscathed. Its famous landmark, the gleaming white Basilica di San Nicola, home to the crypt of St. Nicholas, appeared intact. It was good to know that in the midst of this terrible war, at least the bones of Father Christmas still rested in peace.

No doubt High Command had ordered that the splendid harbor be spared. Bari was a crucial Mediterranean service hub, supplying both the American Fifth and the British Eighth Armies, which comprised the better part of the half-million Allied troops engaged in driving the Germans out of Italy. The grand buildings along the waterfront were the newly designated headquarters of the Fifteenth Air Force, under the command of General James H. Jimmy Doolittle, leader of the daring raid on Tokyo. He had arrived on December first and was busy trying to locate his personnel and get his organization, based seventy-five miles away at the Foggia airfields, off the ground as quickly as possible. Much to Doolittles chagrin, he was only there in a supporting role. The liberating Tommies had already chased the Nazis from the skies over Italy, and his long-range B-17 Flying Fortresses, B-24s, and fighter groups were being brought in to help mop up and expand the strategic bombing campaign against Germany.

The British, who controlled the port, were so confident they had won the air war that, earlier that afternoon, Air Marshal Sir Arthur Coningham had arranged a press conference to announce that Bari was all but immune from attack. Radiating an irritating self-satisfaction, he assured the gathered reporters that the RAF had knocked out the Axis forces in the Mediterranean, adding, I would regard it as a personal affront and insult if the Luftwaffe should attempt any significant action in this area.

The port was teeming with activity. Some thirty Allied shipsBritish, Dutch, Norwegian, and Polishwere crammed into the harbor, taking up every available spot within the breakwater. Four days earlier, the American Liberty ship John Harvey had pulled in with a convoy of nine other merchantmen. The vessels were tightly packed against the seawall and all along the pier, moored so closely they were virtually hull to hull. The dockyards were working around the clock to unload the supplies for the next big pushthe advance on Rome. Allied strategy hinged on making steady progress up the rugged mountainous Italian peninsula, culminating in a proposed amphibious attack at Anzio, about thirty-two miles south of the capital. The success of the advance depended on the long supply line sustaining the march northward. Because of the urgency to keep the incoming stream of war matriel moving to where it was needed most, the usual blackout orders were suspended, and the lights blazed in Bari Harbor all night.

Lang knew the ships holds were laden with tons of vital cargoeverything from food, blankets, and medical gear for hospitals and field aid stations to corrugated steel for landing strips, engines, and fifty-gallon drums of aviation fuel for Doolittles bombers. Visible on the upper decks were vehicles of every kindtanks, armored personnel carriers, jeeps, and ambulancesfull of gas and ready to roll. A procession of tarp-covered trucks lumbered into town, hogging the roads. On the quayside berths, which were all occupied, bright lights winked atop huge cranes that continually hoisted baled equipment up and out. A veritable mountain ridge of boxed ammunition and shells lined the long, broad stone mole, a sign of the heavy fighting that lay ahead.