James Ellman holds a bachelors degree in history and economics from Tufts University and an MBA from Harvard. He has been a successful global institutional investor for the past twenty years. He lives near San Francisco, California.

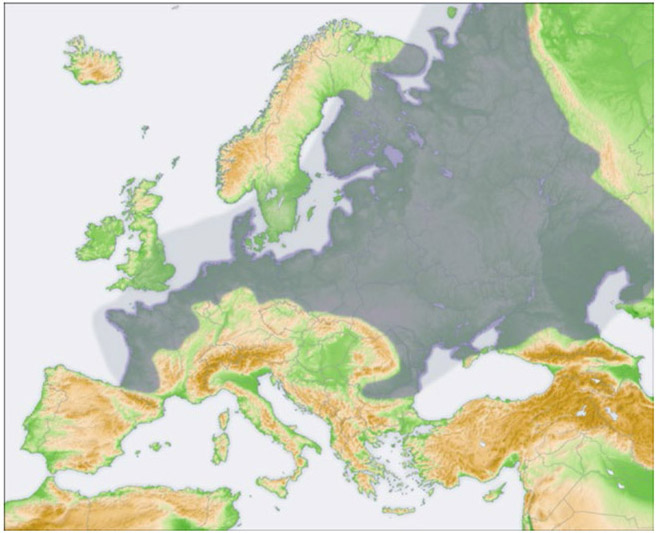

A s with all nations, geography has defined Germanys existence. The country sits on the western side of the European Plain, a generally flat area broken up by forest and the rivers that flow primarily to the North, Baltic, and Black seas. With no defining geographic barrier to stop armies, this region has repeatedly been one of the great battlefields of history. In the centuries before the creation of modern Germany, the Plain provided an easy avenue for invasion and counterattack by the powers of the day. The Romans invaded from the west, and waves of tribal invaders flowed in from the steppe to the east. The Goths, Huns, Franks, Swedes, French, Prussians, and Russians all sent army after army back and forth across these lands.

This geographic position was both Germanys greatest asset and its greatest weakness. As northern Europe became the richest and most powerful part of the world after 1600, Germanys central position on the continent placed it strategically to prosper from the regions growth. An array of navigable riversthe Rhine, the Danube, the Elbe, the Oder, and their tributariesallowed for the economical and rapid movement of goods from the interior of the nation to the coast, facilitating the accumulation of capital at population centers along their banks. This process was accelerated by the Industrial Revolution, mechanization of production, and the expansion of railroads that were most useful in flat areas such as the European Plain. In the late nineteenth century, Germany emerged as a major continental power, defeating its primary rival France in 1870, and embarking on a drive toward economic and military hegemony. To the east, Germany had to contend with the massive but backward Russian Empire. In the west, it was confronted not only by a wary France but also by Britain.

The European Plain (shaded region)

By the start of the twentieth century, France remained a Great Power, but even with its overseas territories it could not keep pace with a rising Germany. Britain was most interested in maintaining its vast empire and ensuring that no hegemonic power arose in Europe that could threaten its command of the seas or penetrate its channel moat. Britain had been happy to side with German states in the 1700s and 1800s to maintain a balance of power against the French. With Teutonic ascendency and the building of the High Seas Fleet, the British backed France to manage the equilibrium. Russia was late to industrialize but was catching up, and its huge population, vast raw materials, and territorial reach offered significant potential. The Russians were also an imperialist power looking to secure greater control of the littorals of the Baltic and Black seas. Such aims were bound to conflict with an equally expansionist Germany no matter who were the leaders in Moscow and Berlin or the ideologies that drove them.

A peaceful continuation of the status quo was made increasingly unstable by Germanys alliance with the Austrian-Hungarian Empire and its kaleidoscope of ethnic nationalities straining for self-determination. A spark was all that was needed to end the peace. That spark was of course ignited in Sarajevo in 1914 with the assassination of the Austrian archduke. So began a thirty-year conflict in which Germany fought to vanquish its continental foes and become a preeminent world power. This struggle only concluded with the final defeat of the last fanatical Nazi soldiers around Hitlers Berlin bunker in 1945.

At the start of the conflict in 1914, the geography the European Plain determined the scope of plans for German conquest just as it would in World War II. As the German armies advanced into France in the opening act of the War to End All Wars, the government of Kaiser Wilhelm under its chancellor, Theobald von Bethmann-Hollweg, established goals for the conflict in what became known as the Septemberprogramm. Despite later protestations that the Allies were just as complicit in the violence of 1914 to 1918, Germanys explicit war aims were aggressive and extreme in scope: in the west, France was to be permanently relieved of its territory along the English Channel, many of its colonies, and its Great Power status. In addition, French trade with the British Empire would be forbidden, and crippling long-term war reparations would be paid to preclude a potential Gallic rearmament program. Luxembourg was to be annexed, Belgium was to become a dismantled vassal state, and the Netherlands would only survive as an economic dependency.

Looking eastward, the German government and its industrial elite concluded that Russia could be defeated first: A separate peace in the east is certain, if Italy does not enter the war. But even if Italy does become involved, the moment may arise in certain circumstances when Russia is no longer willing to continue the war, and we can as a result conclude a separate agreement with Russia. This was a plan to implement what we would now refer to as the war crime of ethnic cleansing. German farmers could only safely move east into newly annexed territories if the established Slavic occupants were forced off their land and into the shrunken remaining domains of the Russian State. The German government realized that such actions would trigger a retaliation by whoever ruled Russia after the war. Thus, much of the German-ethnic minority that had been living in the tsars domains for centuries would be expelled and could be resettled in the newly conquered eastern lands of the expanded Reich. While the German goals of World War I should in no way exonerate Hitler and his henchmen of the crimes committed in the USSR in 1941 to 1944, it is quite clear that the Nazis were following a path blazed by their predecessors.

The greatly expanded German Empire resulting from a successful implementation of the Septemberprogramm would dominate the continent through a Mitteleuropa economic union that would provide for ostensible equality among its members, although it will in fact be under German leadership; it must stabilize Germanys economic predominance in central Europe.

The kaisers government also envisioned that its European continental empire would secure shipments of natural resources from newly created Mittelafrika, stretching from the Atlantic to the Indian oceans and made up of then-current German holdings combined with ceded colonial possessions of France, England, and Belgium.

What is striking is how neatly the goals of the Septemberprogramm match up with the geography of the European Plain. By 1943 the Third Reich achieved these aims for a short period. Hitlers armies conquered most of the Plain after they seized the littoral along the English Channel and the Bay of Biscay in the west, and then pushed to the Volga River in the east. In both world wars, the Germans were motivated by a perceived need to expand to defendable geographic boundaries.

From 1914 to 1918, Germany maximized its three great advantages: interior lines of communications, better artillery, and its Army General Staff, which institutionalized military excellence in planning and battle. These factors allowed the Germans to handily outfight and outkill their opponents. Front lines were pushed back away from the German borders, and the Allies were stretched to the breaking point.

With the signing of the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk, Germany secured its territorial goals in Russia and appeared poised to push on to total victory as it redeployed upward of fifty divisions from the Eastern to the Western Front in early 1918. In the Spring Offensive that followed, the Allied armies were driven back toward Paris, and the Germans seemed on the cusp of victory. However, US troops had begun to arrive in France in late 1917. With them came the first cases of the Spanish flu, which quickly swept across the continent. By the following August, the American Expeditionary Force, with more than one million men, went on the offensive against a German army ravaged by disease. In the end, weight of numbers, a starving German population, and an outsized impact of the global influenza pandemic on the Central Powers won out, leading to an armistice. Instead of shearing off territory from its foes, Germanys borders shrank as it lost 13 percent of its national territory and ceded its overseas colonies. Rather than receiving massive war reparations, Berlin had to make economically debilitating payments to the Allies. The empires of the Central Powers were shattered. In light of the goals of the

![Dzhonatan Dimblbi - Barbarossa: How Hitler Lost the War [calibre]](/uploads/posts/book/898152/thumbs/dzhonatan-dimblbi-barbarossa-how-hitler-lost-the.jpg)