Contents

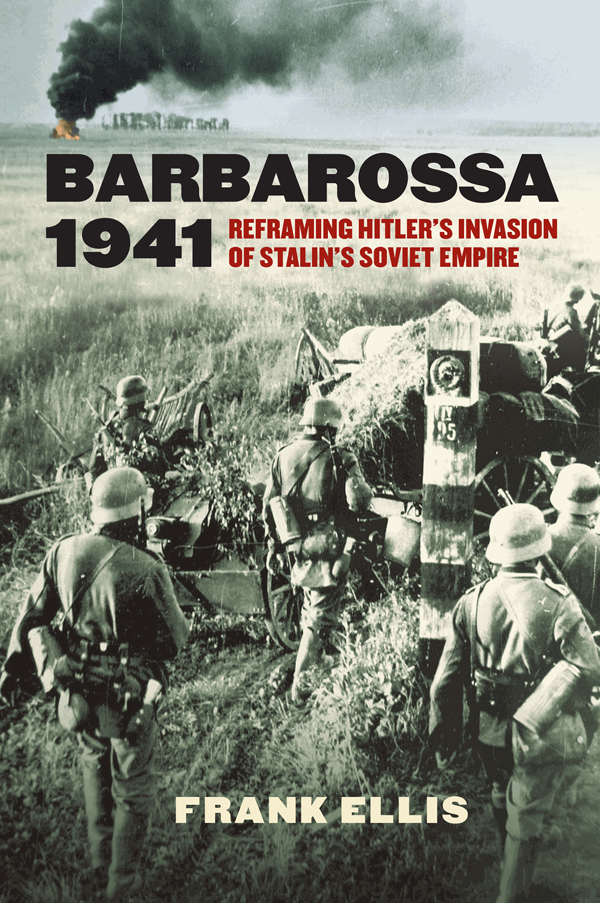

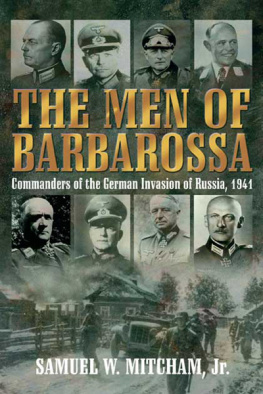

Barbarossa 1941

modern war studies

Theodore A. Wilson

General Editor

Raymond Callahan

Jacob W. Kipp

Allan R. Millett

Carol Reardon

Dennis Showalter

David R. Stone

James H. Willbanks

Series Editors

Barbarossa 1941

Reframing

Hitlers Invasion

of Stalins Soviet

Empire

Frank Ellis

University Press of Kansas

University Press of Kansas

| Published by the University | 2015 by the University Press of Kansas |

| All rights reserved |

| Press of Kansas (Lawrence, |

| Published by the University Press of Kansas (Lawrence, |

| Kansas 66045), which was | Kansas 66045), which was organized by the Kansas |

| Board of Regents and is operated and funded by Emporia |

| organized by the Kansas | State University, Fort Hays State University, Kansas State |

| University, Pittsburg State University, the University of |

| Board of Regents and is | Kansas, and Wichita State University |

| operated and funded by | Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data |

| Emporia State University, | Ellis, Frank, 1953author. |

| Barbarossa 1941 : reframing Hitlers invasion of Stalins |

| Fort Hays State University, | Soviet empire / Frank Ellis. |

| pages cm. (Modern war studies) |

| Kansas State University, | Includes bibliographical references and index. |

| ISBN 978-0-7006-2145-3 (cloth : alk. paper) |

| Pittsburg State University, | ISBN 978-0-7006-2146-0 (ebook) |

| 1. World War, 19391945CampaignsEastern Front. |

| the University of Kansas, | 2. World War, 19391945CampaignsSoviet Union. |

| 3. Soviet UnionHistoryGerman occupation, 19411944. |

| and Wichita State University | I. Title. |

| D 764. e 287 2015 |

| 940.54217dc23 |

| 2015026181 |

| British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data is available. |

| Printed in the United States of America |

| 10987654321 |

| The paper used in this publication is recycled and contains |

| 30 percent postconsumer waste. It is acid free and meets the |

| minimum requirements of the American National Standard |

| for Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials |

| z39.481992. |

There were no reasonable explanations for the Soviet failures, nothing to assuage our humiliation. Poland had been surprised, then stabbed in the back by its eastern neighbor. France had been smaller, weaker than the assailant. But should prodigious Russia two years after the outbreak of war, with every advantage of numbers, time, military concentration, behave like a backward little country caught off guard? Had we been no bigger than France, we would have been crushed four times over in the first four months.

Viktor Kravchenko, I Chose Freedom

A woman had come out onto the road. Vigorously waving as if she was in a cornfield sowing seed, she devoutly made the sign of the cross after the troops. Each company, each platoon, each soldier was blessed with the cross by this Russian woman in the custom of the ancients, according to the ways of our fathers, forefathers and the Heavenly Father, bidding the soldiers well on their long road, for their martial deeds, for the successful completion of the battle on the part of our eternal protectors.

Viktor Astafev, The Damned and the Dead

contents

PREFACE

Given the reinforced library shelves already groaning under the weight of tomes dedicated to Unternehmen (Operation) Barbarossa, the obvious and reasonable question is why another study is required. The answer to this question is essentially one of source material. A large part of this study is based on a number of Soviet documents that were placed in the public domain as part of the declassification process that started in 1991 and continues, intermittently, to this day. The primary documentation I relied on can be found in the relevant volumes of Organy gosudarstvennoi bezopasnosti SSSR v Velikoi Otechestvennoi voine covering the second half of 1941 and the first half of 1942Nachalo 22 iiunia31 avgusta 1941 goda (2000), Nachalo 1 sentiabria31 dekabria 1941 goda (2000), and Krushenie Blitzkriga 1 ianvaria30 iiunia 1942 goda (2003)and the two volumes of documents specifically relating to the period before and just after 22 June 1941 contained in 1941 god (1998).

Although this material has been available to scholars for more than a decade, I am not aware of any study of the central problems associated with BarbarossaSoviet intelligence assessments, German-Soviet diplomacy, and NKVD (Peoples Commissariat of Internal Affairs) operationsbased on a systematic and detailed analysis of the material published in the aforementioned volumes. In makes it quite clear that the Soviet intelligence agencies were doing a thorough and professional job, which makes Stalins failure to act in good time and in good order all the more perplexing. A detailed analysis of the documents raises other intelligence-related questions to which there are no clear answers. For example, is one to assume that the Soviet air force conducted no systematic reconnaissance flights at all over German-controlled territory in the period leading up to 22 June 1941?

German-Soviet diplomatic relations between 1939 and 1941 have been covered in detail by Gerhard Weinberg in Germany and the Soviet Union, 19391941 (1954), although as the author acknowledges, largely on the basis of German sources.

German-Soviet diplomatic exchanges, along with other material, also hint that the Germans were aware of the mass murders of Poles at Katyn and other sites in 1940, carried out by the NKVDs murder squads. If so, the question arises whether knowledge of these murders played a part in the formulation of two of the most notorious orders that emerged from the offices of Hitlers planning staff: Erla ber die Ausbung der Kriegsgerichtsbarkeit im Gebiet Barbarossa und ber besondere Manahmen der Truppe (Decree Concerning the Implementation of Military Jurisdiction in the Barbarossa Zone and Concerning Special Measures for the Troops; hereafter, the Barbarossa Jurisdiction Decree), dated 13 May 1941, and Richtlinien fr die Behandlung politischer Kommissare (Guidelines for the Treatment of Political Commissars; hereafter, the Commissar Order), dated 6 June 1941. It can be argued that even if German planners had foreknowledge of the Katyn murders, this in no way diminishes the criminal nature of the Barbarossa Jurisdiction Decree and the Commissar Order. And if that is the case, one would have expected the Nrnberg prosecutors to pursue the question of responsibility for the Katyn murders with the same determination and dedication with which they looked into the origins, drafting, and execution of the Barbarossa Jurisdiction Decree and the Commissar Order. Unfortunately, they did nothing of the sort. As Robert Conquest has noted, the Katyn murders were examined by the judges at Nrnberg in a derisory fashion. Indeed, the Soviet fiction that the Katyn murders were the work of National Socialist (NS) death squads was upheld and unchallenged.

The Katyn murders are important for an examination of the Commissar Order because Soviet thinking behind the decision to murder Polish prisoners of war has much in common with Nazi thinking behind the decision to kill commissars. This is just one of several indices demonstrating the closeness of the two totalitarian regimes. In my opinion, this ideological propinquity of the Commissar Order and the earlier Katyn Memorandumthe theme of This failure to document Soviet criminality creates a false picture that attributes all the horrors of the mid-twentieth century to the NS regime and implies that they can be understood only by examining the contents of a large black box with a red lid depicting a white circle circumscribing a satanic black

University Press of Kansas

University Press of Kansas