Introduction

What should we do but sing his praise

That led us through the watery maze

Unto an isle so long unknown,

And yet far kinder than our own?

B ERMUDAS , A NDREW M ARVELL , 1654

Now that birdis maybe two hundred years old, Hawkinsthey lives for ever mostly; and if anybodys seen more wickedness, it must be the devil himself. Shes sailed with England, the great Capn England, the pirate. Shes been at Madagascar, and at Malabar, the Surinam, and Providence and Portobello.

L ONG J OHN S ILVER, TALKING OF HIS PARROT , C APTAIN F LINT, IN R OBERT L OUIS S TEVENSONS T REASURE I SLAND , 1883

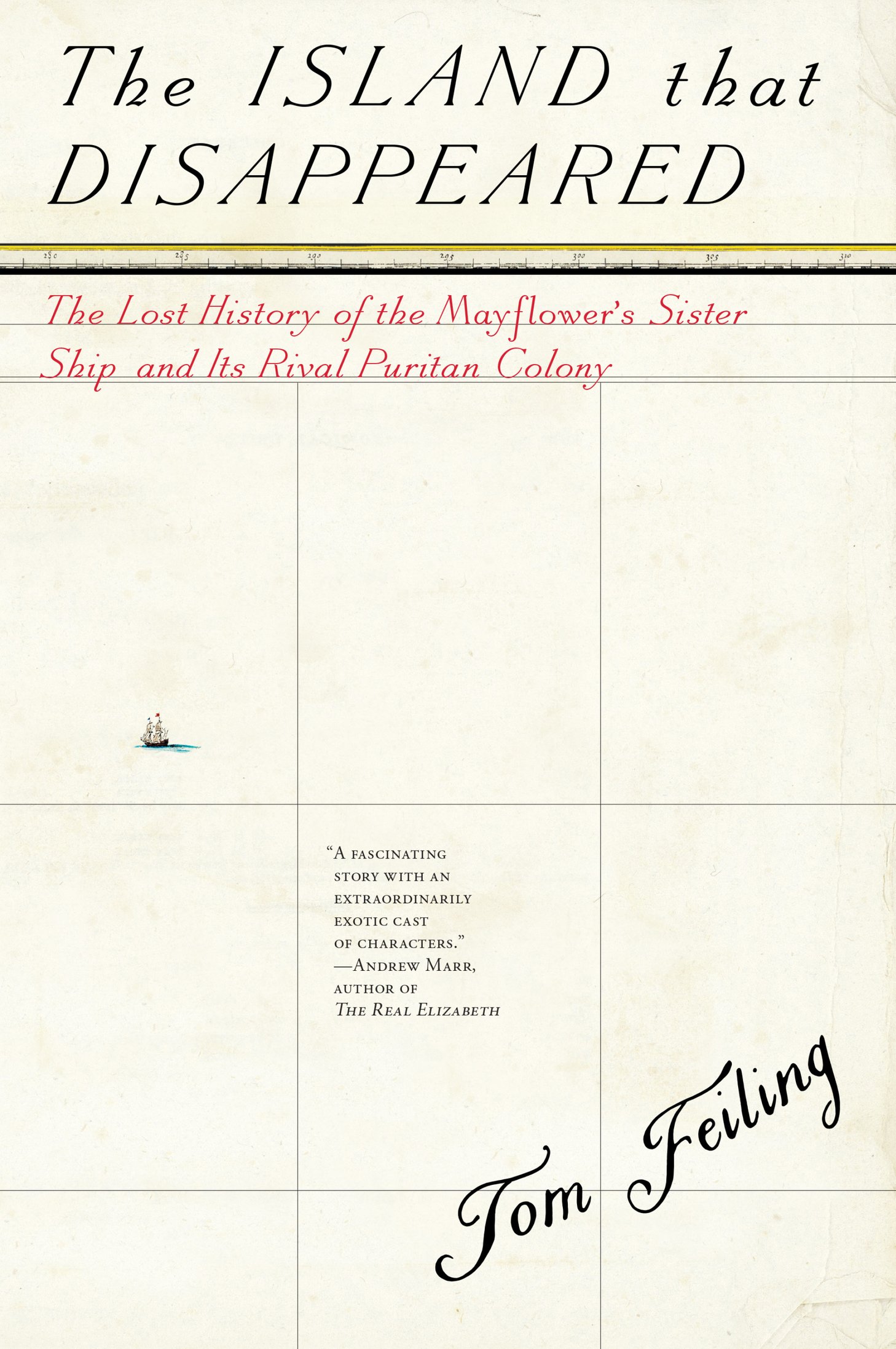

I LIKE TO THINK OF The Island That Disappeared as akin to one of those self-contained wintery worlds encased in thick glass that you find in secondhand shops; a world in miniature; a world familiar, yet made strange by its diminutive size. This book tells the story of Old Providence, a five-mile-long island one hundred fifty miles off the coast of Nicaragua, of which few people in Britain or the United States have ever heard. Though tiny, the island offers a precious view of the Atlantic world in microcosm. The islands history is a rambling trek through four hundred years of Caribbean history. Though the path through time gradually grows narrower and more overgrown as it comes into the modern era, it offers the same broad vistas over the New World in 2017 as it did in 1629, when the first English settlers stumbled onto the islands pristine white sands in search of a refuge from the violence of the Old World.

This book began with a conversation I had with my editor at Penguin a few weeks after the publication of my last book, Short Walks from Bogot: Journeys in the New Colombia. In the course of my research, I had traveled the length and breadth of Colombia, and spoken to a lot of Colombians about their countrys history, politics, and culture. How about writing something similar about the U.K.? she suggested. She received a lot of pitches from British writers proposing to write books about far-flung parts of the world, but few of them seemed interested in reporting on the state of their own country.

This suited me fine; after spending several years in far-flung places, I was keen to know more about my own country. So in the spring of 2012, I bought a camper van and spent the next six months traveling around the country, navigating by a self-imposed rule that I would avoid all towns and cities, and stick to the back roads, guided only by a compass. I wanted to stop thinking about Britain in terms of A to B and instead attune myself to the natural boundaries of cliffs, rivers, and hills. When I wasnt driving, I was sightseeing, and when I wasnt sightseeing, I was reading about British history.

The problem with writing booksas well as sightseeingis that everyone wants to visit the best bits. The Englishlike the Americansthink they have their history sewn up. There are thousands of newspaper columnists and TV producers who take it upon themselves to distill the essence of the national character, as revealed in a series of cherry-picked favorite episodes. They seem content to pore over a tide of books, films, and documentaries that largely rehash what we already know. In order of immediacy, Britains cherries are deemed to be the Second World War (reduced to a simple struggle of good over evil), the First World War (patriotic sacrifice), the Victorians (enterprise, industry, and sexual repression), Elizabeth I (a secular Virgin Mother), and Henry VIII (the original macho brute). The same selective focus is apparent in the United States, where hordes of media producers home in on what they consider the best bits of their history, be it the landing of the Mayflower, the triumph of the Union in the Civil War, or landmark successes in space travel.

One evening in midsummer, I parked up outside a small, isolated church near Stokesay in Shropshire. I was too cut off from everything to know it, but that night, Danny Boyle would present his take on the meaning of Britains history at the opening ceremony of the Olympic Games in London. While he was transmogrifying Englands dark Satanic Mills to become the postwar light that is the National Health Service, I was reading about the English Civil War in the van.

Why did I know so little about Englands last and greatest domestic conflagration? I wondered. Somewhere along the way, I had picked up the bare bones of the plot: how the Roundheads fought the Cavaliers, and Charles I ended up losing his head. But the hours I had spent watching history documentaries on BBC2 had given me next to no understanding of the causes of a war that raged for over ten years and killed two hundred fifty thousand Britons.

As I read more about the English Civil War, I was struck by mention of the Providence Island Company. It was not often mentioned, but among its members were most of the Puritan nobles who had led Parliament into war against the king. ProvidenceI recognized the name from my time in Colombia. The congressman who represents the department of San Andrs and Providencia is the only native English speaker in the chamber. Since the islands are five hundred miles north of the mainland, most Colombians dont pay them much attention. While living in Colombia, I had, like them, occasionally wondered about tiny Providence, cut adrift one hundred and fifty miles off the Miskito Coast of Nicaragua, but not enough to visit.

Guided by an inkling that the island had something new and original to tell me about England, I began trawling the Internet for leads. I discovered that the Providence Island Companys records had been lost for two hundred fifty years. Only in 1876 did the archivists at the U.K.s Public Record Office realize that the records had been mistakenly filed under New Providence, the first English settlement on the Bahamas. In fact, Old Providence predates both New Providence and Providence, Rhode Island. I ordered the only three books to have been written about the place, and began reading.