Roanoke Island

1983 by The University of North Carolina Press

All rights reserved

Manufactured in the United States of America

08 07 06 05 04 14 13 12 11 10

Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data

Stick, David, 1919

Roanoke Island, the beginnings of English America.

Published for Americas Four Hundredth Anniversary Committee.

Includes index.

I. Roanoke Island (N.C.)History. 2. AmericaDiscovery and explorationEnglish. I. North Carolina. Americas Four Hundredth Anniversary Committee. II. Title

F262.R4S74 1983 975.6175 83-7014

ISBN 0-8078-1554-3

ISBN 0-8078-4110-2 (pbk.)

Americas Four Hundredth Anniversary Committee and the University of North Carolina Press gratefully acknowledge the support of the Integon Foundation in the publication of this book.

THIS BOOK HAS BEEN DIGITALLY PRINTED.

In memory of

HERBERT R. PASCHAL, JR.

Friend, scholar, and leader in planning Americas Quadricentennial

Preface

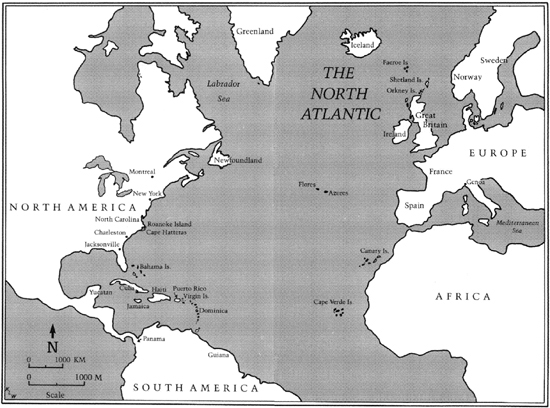

Twenty-two years before John Smith and the Jamestown settlers first sighted Chesapeake Bay and thirty-five years before Mayflower reached the coast of Massachusetts, the first English colony in America was established on Roanoke Island, in what is now North Carolina.

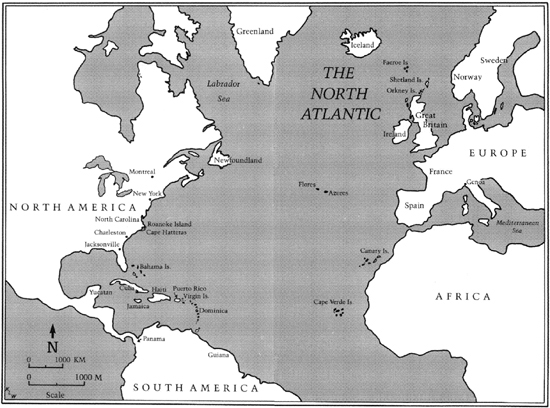

Explorers sent out by Sir Walter Raleigh landed on the North Carolina Outer Banks in 1584, taking possession in the name of Queen Elizabeth. Between then and 1587 there was a steady stream of shipping between England and Raleighs Roanoke Island settlement, with such renowned Elizabethans as Sir Francis Drake and Sir Richard Grenville taking part. The vast area covered by Raleighs patent, comprising much of what is now the United States, was named Virginia in honor of the Virgin Queen. A force under Ralph Lane spent a year there, exploring as far north as Chesapeake Bay, inspecting most of the villages in the Albemarle Sound area, and traveling far up the Chowan and Roanoke rivers.

Permanency seemed assured in 1587 when a colony of men, women, and children arrived at Roanoke Island. That summer the Indian Manteo was baptizedthe first Protestant baptism in the New World. A baby girl, Virginia Dare, was bornthe first child born of English parents in America. But for the next three years all efforts to provide relief for the settlement were thwarted by war with Spain and by King Philips mighty Spanish Armada. When an expedition finally arrived in 1590, the settlers had disappeared, to be known thereafter as Sir Walter Raleighs lost colony.

As the four hundredth anniversary of Raleighs settlements and the lost colony approaches, it is important to focus attention on Roanoke Island and the beginnings of English America. Much has already been written about these colonization efforts, but the bulk of it has been either too scholarly to hold the attention of the lay reader, or fictionalized. This book has been written at the request of Americas Four Hundredth Anniversary Committee to fill a void between those scholarly and fictionalized works. The specific charge to the author was to produce a concise, accurate, popularly written book for the average reader. Certainly, after much cutting and rewriting, it is concise; and every effort has been made to ensure its accuracy. It remains for the individual reader to judge the popularity of the style.

William S. Powell, publications chairman of the Four Hundredth Anniversary Committee and long-time friend and fellow historian, has provided guidance and encouragement from the outset, and has carefully read and edited the manuscript in two different stages. John D. Neville, Philip W. Evans, and the late Herbert R. Paschal, Jr., provided valuable input as the book took shape. Wynne C. Dough, associate and adviser, has corrected spelling and punctuation, double-checked sources, and read proofs, all with no outward sign of complaint. David Perry has edited the book for the University of North Carolina Press and has seen it through the various phases of the publication process.

It is impossible for anyone writing about Raleigh and his colonies to express adequate appreciation to David B. Quinn, and his wife and research associate, Alison M. Quinn, for bringing together the source material. To a large degree their efforts have made it possible for the rest of us to understand what went on here and in England four hundred years ago. And without the writings of Arthur Barlowe, Ralph Lane, and Thomas Hariotand the accounts and drawings of John Whiteso ably published four centuries ago by Theodor de Bry and Richard Hakluyt, we would have little accurate information from which to draw for this story of true adventure.

From the outset it was the intent of Americas Four Hundredth Anniversary Committee, in this day of escalating publication costs, to make this book available in both hardbound and paperback editions at a reasonable price. A generous publishing subvention by the Integon Foundation, Inc., has made this possible.

David Stick

Kitty Hawk

February, 1983

Introduction

Anyone making a study of the early European efforts to colonize America must inevitably ask the question: Why were the English so late getting into the act?

As every school child knowsor should knowthe first voyage of discovery by Columbus was in the year 1492. Yet it was nearly a century later, in the 1580s, when men, women, and children sent out by Sir Walter Raleigh established the first English colonies in Americaon Roanoke Island, in an area the Elizabethans called Virginia, now the state of North Carolina.

In order to understand the reasons for this late start by the English it is necessary to review the history of European discovery and settlement in America, and to gain an understanding of the extent of mans knowledgeor lack of knowledgeof world geography in the centuries preceding permanent settlement in this hemisphere.

Following his discovery of America, Columbus made three more voyages across the Atlantic, exploring the islands of the Caribbean and touching on the coasts of both Central America and South America. Yet he had no understanding of where he had been, let alone any awareness of the magnitude of his discoveries.

In fact, Columbus died in the firm belief that he had reached the Indies, a name applied in the fifteenth century to a vast area that included China, Japan, and the islands of Indonesia. He was certain when he arrived in the Caribbean that he was really just off the coast of Cathay, or China, and that Cuba was actually the legendary Cipango, or Japan.

If voices were raised back in Europe suggesting that Columbus was in error, and that in fact he had discovered a previously unknown hemisphere midway between Europe and Asia, they were quickly stilled. The returning hero had reached the Indies. The natives he encountered in that far-off land were thus Indians. And to this day the islands he really discovered in the Caribbean are known as the West Indies, not to be confused with those on the other side of the world he thought he had reached, the East Indies.

The Columbus mistakeroughly equivalent to our astronauts landing on a previously unknown planet instead of the moon and not knowing the differenceis understandable when one considers the limited knowledge of world geography five hundred years ago. Nearly two thousand years earlier some scientists and philosophers had concluded that the earth was round, largely as a result of data developed by Aristotle and Eratosthenes. But information was lacking on the size of the earth, on the portions of the surface covered by land or by water, and on the shape and extent of the land masses.