GRAVEYARD OF THE ATLANTIC

Stick/Graveyard of the Atlantic

1952 The University of North Carolina Press

All rights reserved

Manufactured in the United States of America

ISBN 978-0-8078-0622-7

ISBN 978-0-8078-4261-4 (pbk.)

Library of Congress Catalog Card Number 53-10253

cloth 05 04 03 02 01 27 26 25 24 23

paper 11 10 09 08 07 13 12 11 10 9

To my wife,

PHYLLIS,

who shared equally in the tiring

work of research for this book, but

not in the pleasure of writing it.

FOREWORD

Men like captain hand, the only survivor of the loss of the sloop Henry at Ocracoke in 1819; and Ensign Lucian Young, hero of the wreck of the U.S. gunboat Huron at Nags Head in 1877; and Dunbar Davis of South-port, who devoted most of his life to saving mariners wrecked on the North Carolina coast, deserve the bulk of the credit for this book. For without the detailed information on disasters recorded by these and other participants, factual accounts of bygone shipwrecks could not now be written.

Even so, it has been necessary to eliminate a major share of the thousands of shipwreck accounts examined in the compilation of material for this book, for only those vessels which are definitely known to have been total wrecks are listed here. Many other ships were lost before accurate records were kept; hundreds more just disappeared, with no trace of ship or crew, or have been surrounded by such confusion and conflict as to dates, places, and circumstances that they had to be eliminated.

The material included here comes from newspapers, magazines, books, pamphlets, official records, and personal interviews. Special thanks are due my father, Frank Stick, for taking time out from his busy schedule to do the fine pen and ink drawings that enliven the accounts to follow; and John L. Lochhead and the staff of the Mariners Museum at Newport News, Virginia; Mary Brown and her co-workers in the Norfolk Public Library; the United States Hydrographic Office, the United States Coast Guard, the United States Navy, the National Archives, and the Library of Congress; L. F. Small, Huntington Cairns, John C. Emmerson, Jr.; A. W. Drinkwater, Aycock Brown, Ben Dixon MacNeill, Levene Midgett, T. S. Meekins, W. H. Lewark, Marianne C. Small, Joseph Hergesheimer, and the friends and members of my family who have encouraged and assisted during the days when the task seemed never ending.

Limitations of space have made necessary the abbreviation of some wreck accounts which, in the opinion of this writer, have already received more than their proportionate share of publicity and recognition. In other instances there is no mention at all of supposed wrecks about which the old-timers speak because exhaustive research has failed to substantiate the stories handed down from past generations. And finally, except in special cases, losses in inland waters, and of vessels of less than fifty tons, have been eliminated.

Even so, more than six hundred wrecked vessels are mentioned in the pages that follow. All were totally lost in the Graveyard of the Atlantic.

David Stick

Kill Devil Hills, N.C.

September 12, 1951

CONTENTS

THE OUTER BANKS 15261814

You can stand on Cape Point at Hatteras on a stormy day and watch two oceans come together in an awesome display of savage fury; for there at the Point the northbound Gulf Stream and the cold currents coming down from the Arctic run head-on into each other, tossing their spumy spray a hundred feet or better into the air and dropping sand and shells and sea life at the point of impact. Thus is formed the dreaded Diamond Shoals, its fang-like shifting sand bars pushing seaward to snare the unwary mariner. Seafaring men call it the Graveyard of the Atlantic.

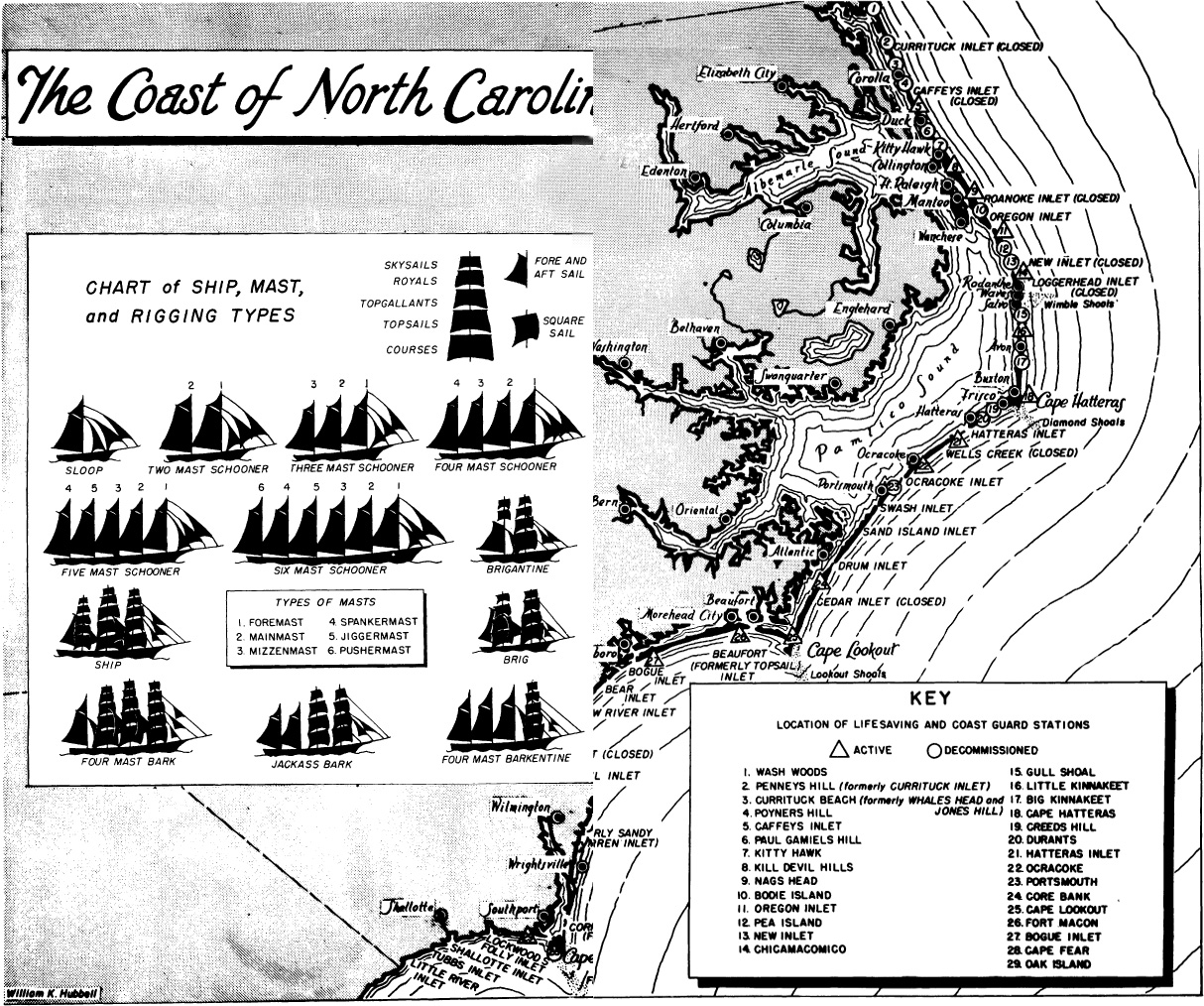

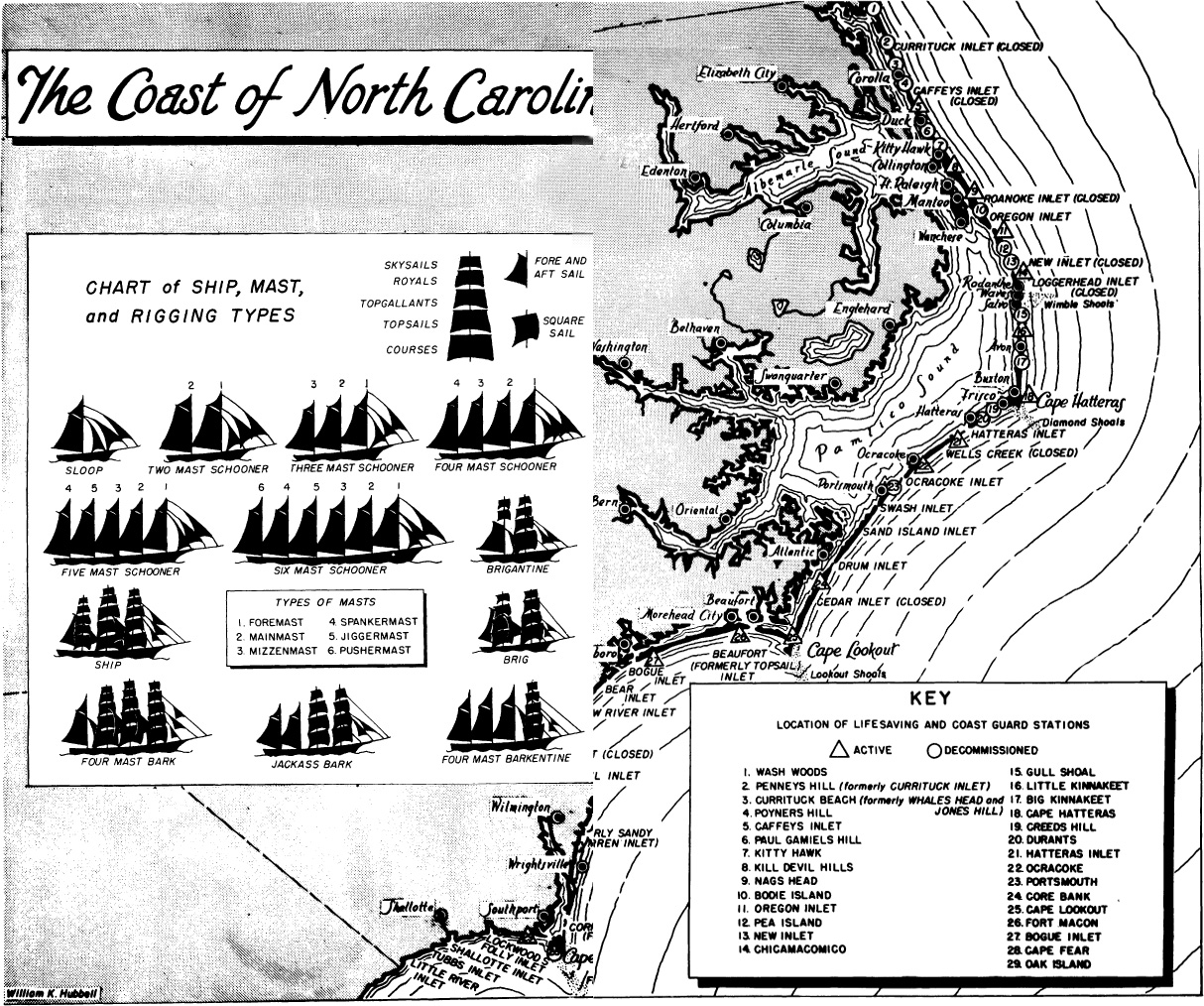

Actually, the Graveyard extends along the whole of the North Carolina coast, northward past Chicamacomico, Bodie Island, and Nags Head to Currituck Beach, and southward in gently curving arcs to the points at Cape Lookout and Cape Fear. The bare-ribbed skeletons of countless ships are buried there; some covered only by water, with a lone spar or funnel or rusting winch showing above the surface; others burrowed deep in the sands, their final resting place known only to the men who went down with them.

From the days of the earliest New World explorations, mariners have known the Graveyard of the Atlantic, have held it in understandable awe, yet have persisted in risking their vessels and their lives in its treacherous waters. Actually, they had no choice in the matter, for a combination of currents, winds, geography, and economics have conspired to force many of them to sail along the North Carolina coast if they wanted to sail at all.

A great number of the craft lost in the Graveyard of the Atlantic were engaged in coastal trade, transporting cargoes from north to south or back again in the days before the advent of airlines, highways, and fast railroad service. They were small vessels, mainly, and a constant stream of them connected the vast productive lands of the South with the cities on the Chesapeake and the manufacturing centers of the Central Atlantic States and New England.

For all their numbers and the frequency of their losses, the vessels of the coastal trade were no more a factor in the over-all history of Carolina shipwrecks than were the larger craft engaged in trade with South America, the West Indies, and our own Gulf Coast. For they, too, were forced to pass the Carolina outer banks if their cargoes were to be delivered to the northern markets, and many a shipload of coffee and sugar, of salt and spice, of logwood and phosphate, has been consigned to the depths off Frying Pan and Lookout and Diamond Shoals as a result.

More difficult to understand is the reason for the loss here of so many vessels engaged in transoceanic trade, ships of many nationalities, of almost every shape and size, bound to and from the ports of Europe, Africa, and even Asia. What reason could there be, for example, for a seventeenth-century Spanish frigate, en route from Central America to her home country, purposely sailing a thousand miles out of her way to pass within sight of dreaded Diamond Shoals; or for an English brigantine of the eighteenth century travelling by such a circuitous route from the British Isles to New York as to end up on Ocracoke Bar, pounded to pieces in the surf, a total wreck?

The Gulf Stream figures in the answer to both questions, for the Spanish explorers learned, even before our coast was first settled by Europeans, that they could save considerable time on their return voyage from the Caribbean to Spain by taking advantage of the Gulf Stream current, travelling northward along the coast until they sighted Cape Hatteras, then bearing east for the shorter trip across the Atlantic. And, by the same token, the vessels bound to this hemisphere soon devised a system of sailing southward along the coast of Europe and Africa until they reached the Canary Islands, then crossing in the Equatorial Current to the West Indies, and finally moving up the coast with the aid of that same Gulf Stream.

In either case the first land jutting out across their path on the run northward was the section of the Carolina outer banks extending like a huge net from the South Carolina border to Cape Hatteras, a long, sweeping series of shoal-infested bights and capes and inlets, laid out as if by perverted human design to trap the northbound voyager.

Next page