Foreword

SERIOUS RESEARCH for this book was begun more than ten years ago, but it soon became apparent that so much interesting material was available on the subject of Outer Banks shipwrecks that the book was threatened at the outset with being overloaded with accounts of ship sinkings. Consequently, I digressed from the main subject long enough to devote a full volume to shipwrecks, and this was published under the title Graveyard of the Atlantic.

For several years the research was continued on a part-time basis. Then a project was instituted by the National Park Service to compile basic information on the Outer Banks and the Cape Hatteras National Seashore Area. A grant was made to the Coastal Studies Institute of Louisiana State University for studies on the geological formation, geographical history, archaeology, and natural history of the Banks. At approximately the same time, a grant was offered me by the Old Dominion Foundation, through the Eastern National Park and Monument Association, to enable me to continue with my historical research, and I should like at this time to gratefully acknowledge this financial assistance which made it possible for me to work full time on the project in 1955 and 1956. One direct result of this was a close working agreement with the Coastal Studies Institute personnel, particularly Gary S. Dunbar who prepared the geographical history of the Banks. In one important area, the study of census returns, I have relied entirely on his research; and his many constructive criticisms are deeply appreciated.

Because of limited research facilities in the Banks area, it has been necessary for me to acquire my own library of books, pamphlets, periodicals, maps, photostats, and microfilm copies of manuscript material concerning the area, and I wish to make a special acknowledgment of the invaluable assistance of the many antiquarian booksellers who have located Banks material for me. Without my library I could never have written this book, and without the cooperation of the antiquarian booksellers, I could never have put together the library.

I am indebted, equally, to a large number of librarians, writers, researchers, and friends who have known that I was attempting to learn everything I could about the Outer Banks and who have let me know whenever they came across pertinent material. Their unselfishness and thoughtfulness have more than compensated for the frustrations, distractions, and disappointments with which research is periodically marked.

I doubt that my wife Phyllis has paused long enough from her household chores these past few years to realize how important it is to a writer to have a wife who herds the children into the other end of the house on rainy days, keeps visitors away from my study when I am trying to write, serves my meals at whatever odd hours I may call for them, and is always on the alert to sense my mood and offer encouragement when it is needed.

In the chapter references at the end of the book I have mentioned many of the individuals who have contributed specific information, though the continued encouragement and help of Huntington Cairns, Aycock Brown, and my mother, Maud Hayes Stick, should be acknowledged separately.

The first draft of the manuscript was written while I was living on the beach at Kill Devil Hills, with a view of the ocean from my study, and this final rewriting has been done on Colington Island, with Roanoke Sound just below my window. Yesterday, at dawn, the broad expanse of that sound was calm and peaceful, its surface mirroring many-hued reflections from the rising sun; last night a soft breeze ruffled the water and the three wild ducks which have stayed on here this spring took refuge in our cove. This morning I understand why, for the wind is blowing at gale force and the waves are breaking like ocean seas, submerging our little dock each time one rolls in to shore. Already my old skiff is sunk at the landing, and a branch from our big live oak has fallen across the swing, which means there will be work other than writing to be done tomorrow. But that's the way it is here on the Banksand, anyway, the story is now written.

DAVID STICK

Colington, N. C.

April 6, 1958

Sands, Sounds, and Inlets

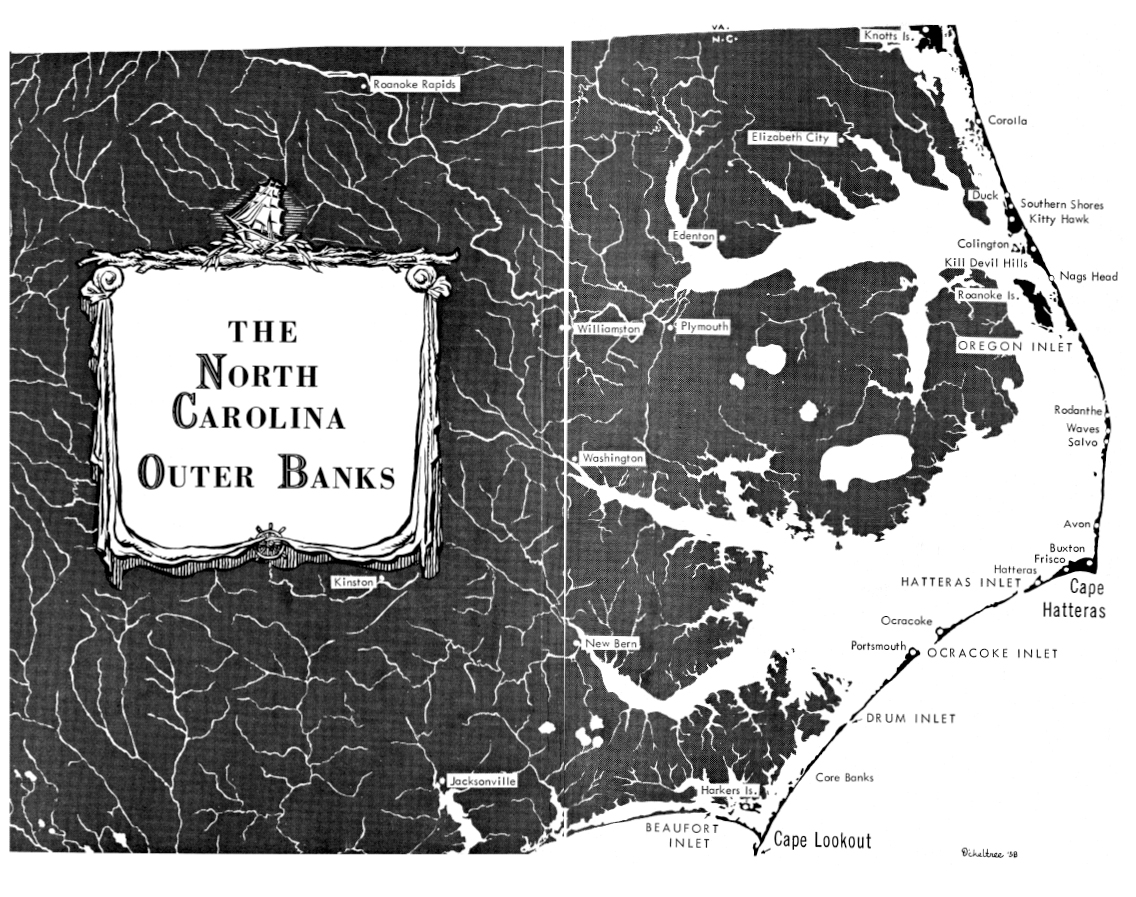

STRETCHING ALONG the North Carolina coast for more than 175 miles, from the Virginia line to below Cape Lookout, is a string of low, narrow, sandy islands known as the Outer Banks. They are separated from the mainland by broad, shallow sounds, sometimes as much as thirty miles in breadth, and are breached periodically by narrow inlets which are forever opening and closing.

In the center, at Cape Hatteras, the Banks jut out so far into the Atlantic that the Gulf Stream currents caress the shoals, warming the atmosphere and making it possible for tropical fruits and plants to thrive, and for pelicans to fish along the shore. Here the northbound Gulf Stream swerves out to sea as it encounters the cold waters coming down from the Labrador Current, and at the junction of the two is Diamond Shoals, the Graveyard of the Atlantic, a point of constant turbulence and of countless shipwrecks.

Above Cape Hatteras, on the North Banks, is Kill Devil Hills, scene of the Wright brothers first flights in a heavier-than-air machine. Opposite, on Roanoke Island, is Fort Raleigh, site of the attempts at English colonization in America under Sir Walter Raleigh in the 1580s and of the lost colony of 1587. Between the North Banks and Cape Hatteras are Bodie Island, Oregon Inlet, and Chicamacomico Banks, long stretches of open beach and surf, teeming with fish, dotted with the broken remnants of wrecked vessels.

Below Cape Hatteras the Banks turn sharply toward the west to Ocracoke, where the pirate Blackbeard was killed, and on to Portsmouth, Core Banks, Cape Lookout, and beyond to Shackleford Banks and Beaufort Inlet.

Since the early colonial days these Outer Banks have formed a barrier blocking the passage of large ocean-going vessels and retarding the commerce and prosperity of northern Carolina. At the same time, however, they have served as a natural breakwater, protecting the mainland areas against the ravages of sea and storm. Were it otherwise the coast would be far inland along the plain, and the small towns on the shores of Pamlico and Albemarle sounds, and along the Neuse and Pamlico rivers, might be major port citiesif they were there at all.