Michael Leroy Oberg - The Head in Edward Nugents Hand: Roanokes Forgotten Indians

Here you can read online Michael Leroy Oberg - The Head in Edward Nugents Hand: Roanokes Forgotten Indians full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2013, publisher: University of Pennsylvania Press, genre: Home and family. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:The Head in Edward Nugents Hand: Roanokes Forgotten Indians

- Author:

- Publisher:University of Pennsylvania Press

- Genre:

- Year:2013

- Rating:5 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

The Head in Edward Nugents Hand: Roanokes Forgotten Indians: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "The Head in Edward Nugents Hand: Roanokes Forgotten Indians" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

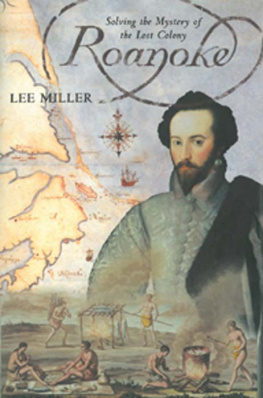

Roanoke is part of the lore of early America, the colony that disappeared. Many Americans know of Sir Walter Raleghs ill-fated expedition, but few know about the Algonquian peoples who were the islands inhabitants. The Head in Edward Nugents Hand examines Raleghs plan to create an English empire in the New World but also the attempts of native peoples to make sense of the newcomers who threatened to transform their world in frightening ways.

Beginning his narrative well before Raleghs arrival, Michael Leroy Oberg looks closely at the Indians who first encountered the colonists. The English intruded into a well-established Native American world at Roanoke, led by Wingina, the weroance, or leader, of the Algonquian peoples on the island. Oberg also pays close attention to how the weroance and his people understood the arrival of the English: we watch as Winginas brother first boards Raleghs ship, and we listen in as Wingina receives the report of its arrival. Driving the narrative is the leaders ultimate fate: Wingina is decapitated by one of Raleghs men in the summer of 1586.

When the story of Roanoke is recast in an effort to understand how and why an Algonquian weroance was murdered, and with what consequences, we arrive at a more nuanced and sophisticated understanding of what happened during this, the dawn of English settlement in America.

Michael Leroy Oberg: author's other books

Who wrote The Head in Edward Nugents Hand: Roanokes Forgotten Indians? Find out the surname, the name of the author of the book and a list of all author's works by series.