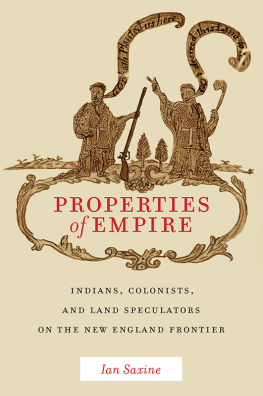

A volume in the series

Native Americans of the Northeast

Edited by

Colin Calloway

Jean M. OBrien

Barry OConnell

Copyright 2014 by University of Massachusetts Press

All rights reserved

Printed in the United States of America

ISBN 978-1-62534-083-2 (paper); 082-5 (hardcover)

Designed by Dennis Anderson

Set in Adobe Jenson Pro by House of Equations, Inc.

Printed and bound by Sheridan Books, Inc.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Winslow, Edward, 15951655.

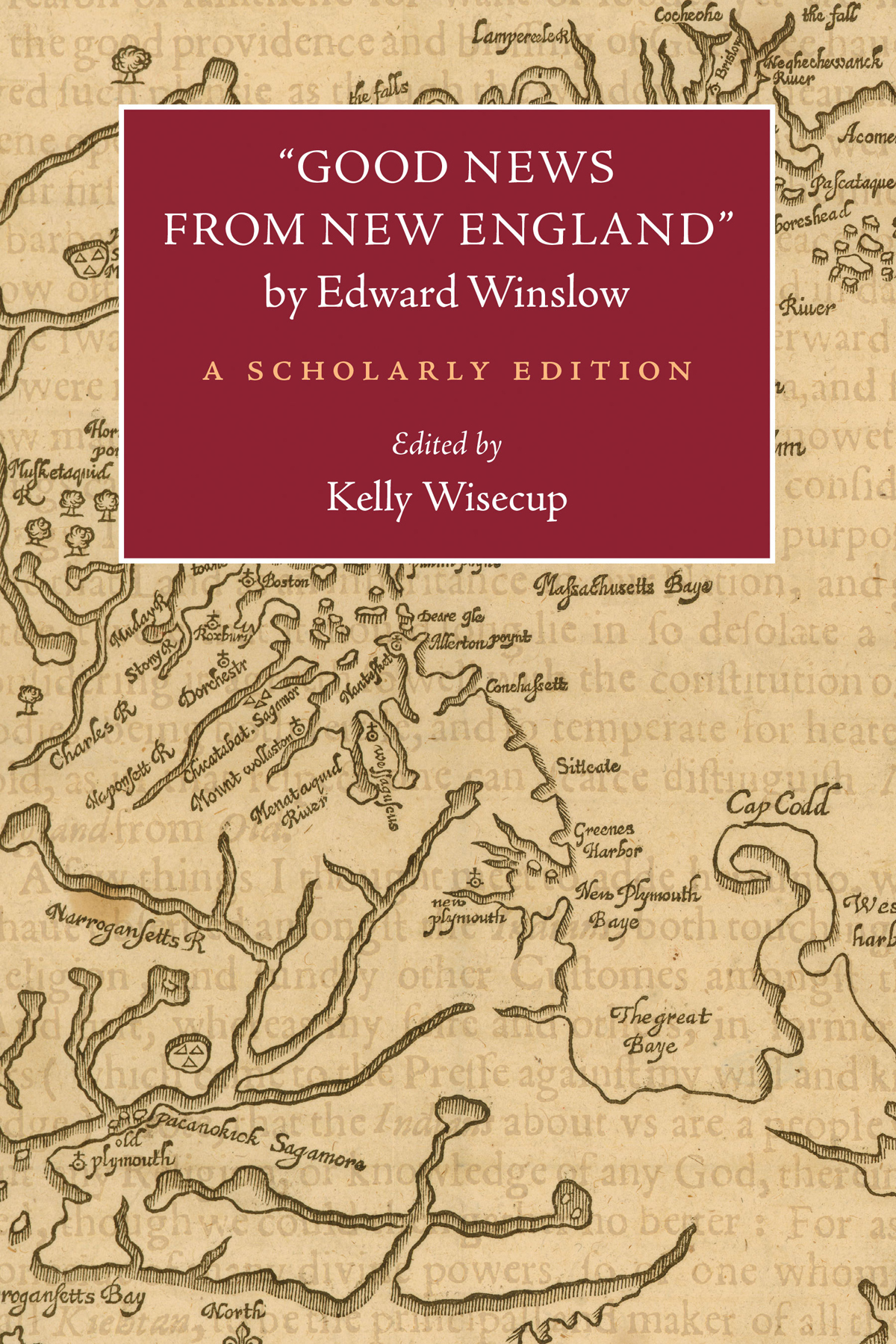

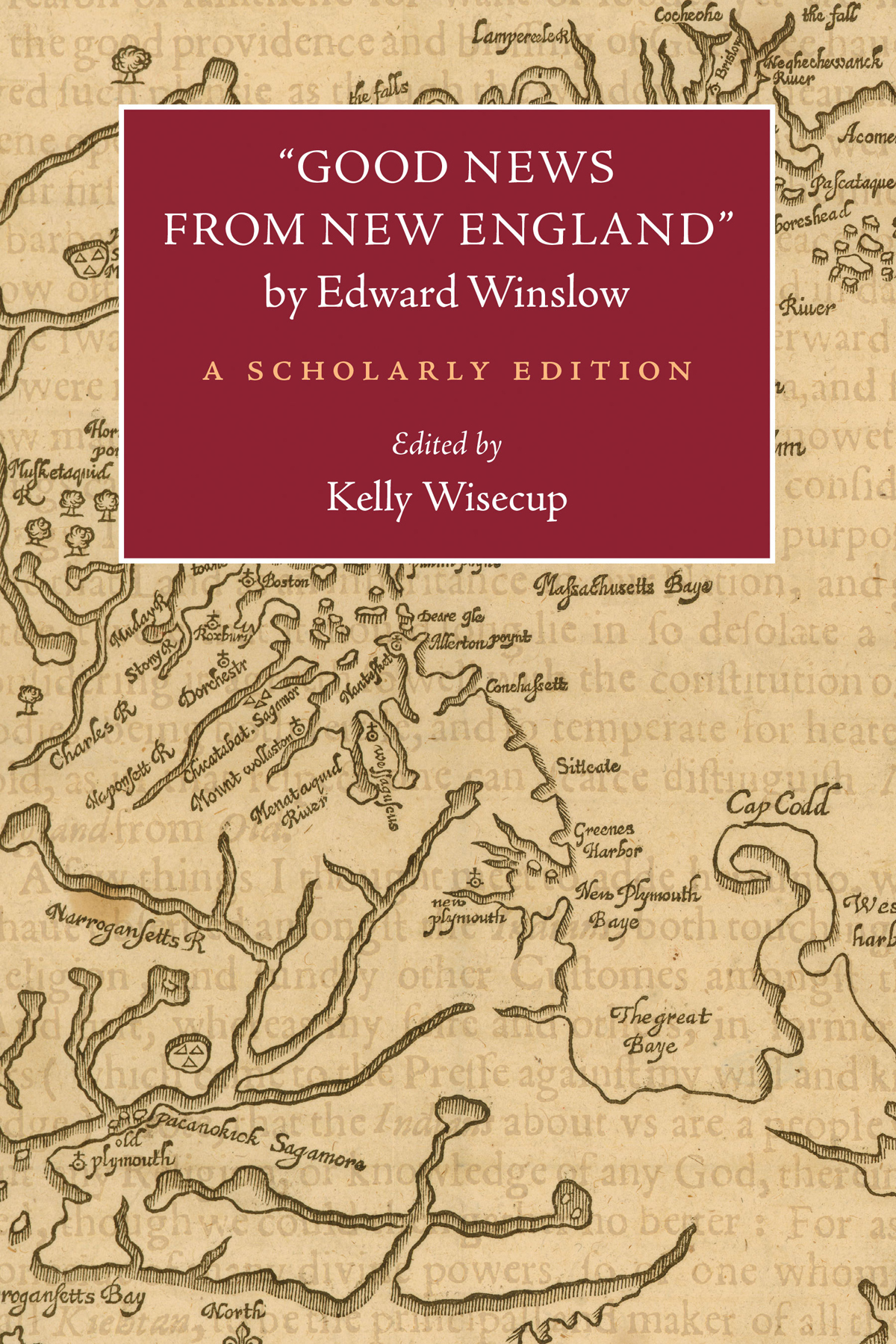

Good news from New England / by Edward Winslow; edited by Kelly Wisecup. A scholarly edition. pages cm. (Native Americans of the Northeast)

Originally published: London : Printed by I. D. John Dawson for W. Bladen and J. Bellamie, 1624.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-1-62534-082-5 (hardcover : alk. paper) ISBN 978-1-62534-083-2 (pbk. : alk. paper)

1. MassachusettsHistoryNew Plymouth, 16201691.

2. Pilgrims (New Plymouth Colony)Early works to 1800. [1. Indians of North AmericaMassachusetts.] I. Wisecup, Kelly, 1981 II. Title.

F68.A66 2014

974.402dc23

2014008144

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Thanks to Matt Cohen and Karen Ordahl Kupperman for their longstanding enthusiasm and support for this project and to Meghan Hughes Morton for sharing my interest in Winslow early on. Matt, Gabriel Cervantes, Alex Pettit, Dahlia Porter, and Cassander Smith provided helpful feedback on the introduction. In addition, Drew Lopenzina pointed me to Iroquois interpretations of arrows bound together, Ives Goddard commented on Winslows spelling of Massachusett animate nouns, and Stephen Foster suggested references on John Bellamie. Elizabeth Veisz helped with research logistics and travels throughout Massachusetts during the summer of 2012. Thanks also to my graduate assistant, Erin Stalcup, for her expert work, and to the undergraduate students in my spring 2011 and 2013 ENGL 3912 courses, for helping me to consider how Good News is received in the classroom.

The staff at the John Carter Brown Library all provided immensely helpful feedback and resources during the summer of 2012, which made it a pleasure to do the research for this edition. Thanks especially to Val Andrews, Kim Nusco, Ken Ward, Leslie Tobias Olson, and John Minichiello. Im also grateful to the Boston Public Library, the Massachusetts State Archives (especially Jennifer Fauxsmith), Pilgrim Hall Museum (especially Stephen ONeill), Plimoth Plantation (especially Karin Goldstein and Bob Charlebois), the Tomaquag Indian Memorial Museum (especially Lorn Spears), the Massachusetts Historical Society, Old Bridgewater Historical Society, the Huntington Library, the British Library, the Newberry Library, the Library Company of Philadelphia, and the Rhode Island Historical Society.

At University of Massachusetts Press, I thank Clark Dougan, Bruce Wilcox, Carol Betsch, and the editors of the Native Americans of the Northeast series, Colin Calloway, Barry OConnell, and Jean OBrien, for their support of the edition and assistance along the way. Thanks as well to two anonymous reviewers, whose comments improved the edition.

The research for this edition was made possible by a fellowship from the John Carter Brown Library and by the Small Grant Program at the University of North Texas. Thanks also to the Department of English at UNT (especially to David Holdeman and Diana Holt) for supporting the edition with a Research Assistant Grant and with funds to offset the costs of reproducing images.

Finally, I thank Yale University Press for permission to reprint selections from The Voyages of Giovanni da Verrazzano, 15241528, ed. Lawrence C. Wroth (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1970), 13536.

INTRODUCTION

In the winter of 1622, word traveled throughout southern New England that the sachem, or leader, of the Pokanoket Wampanoags had fallen ill. Massasoit, or Ousemequin, as the sachem was known, had been unable to eat for several days, his tongue had swollen to such a size that he was unable to swallow, and he was losing his sight.

Massasoits subjects in nearby Wampanoag communities and his allies also traveled to his village, at a place called Sowams (near what is now Bristol and Warren, R.I.), some of them from distances as great as one hundred miles. In this way, they followed Algonquian customs for The presence of powahs and allies alike made the sachems sickbed a site where spiritual and political relationships were strengthened and negotiated.

One of these allies, an English colonist named Edward Winslow, also hoped to profess his friendship to Massasoit, and, like Massasoits Algonquian visitors, he traveled the roughly forty miles from his villagewhich Native people called Patuxet but English colonists renamed Plimothto Sowams.

Massasoit accepted the conserves, and, to everyones surprise, he was able to swallow the juice from the concoction. The next morning, Massasoit directed Winslow to provide the same medical care to other Wampanoag people who were ill.

Massasoits requests not only ensured that he and his people would receive medical care from a man who was the colonists primary diplomat to the Wampanoags but also incorporated Winslow into their networks Indeed, Massasoit himself reciprocated Winslows gift of medical care: he instructed Hobbamock to inform the colonist that the Massachusett people, who lived north of the Wampanoags, were planning to attack a second English colony, called Wessagusset. The Massachusetts also, Massasoit stated, planned to strike Plimoth before the colonists could counterattack.

By providing Winslow with information about the Massachusetts alleged plot, Massasoit also reminded him of the alliance the colonists and Wampanoags had made in 1621, in which each group agreed to defend the other. Sharing the news of the Massachusetts plan allowed Massasoit to confirm his status as a trustworthy ally of the colonists. After Winslow returned to Plimoth and relayed the sachems statements, the colonists decided to act on the information by attacking the Massachusetts first. Plimoths military leader, Myles Standish, chose a few colonists and traveled to Wessagusset, where they killed a total of seven Massachusett men, by trapping some of them in a room and by attacking others in a fight that took place outside the settlement. The colonists cut off the head of a Massachusett leader (probably a pniese) named Wituwamat and carried it back to Plimoth, where they mounted the dismembered head on a pole, as a warning and terrour to all of that disposition, that is, to all who threatened the colonists.

English readers encountered the stories of Massasoits illness and of the Plimoth colonists attack in Winslows printed account, a narrative called Good News from New England, which offered a history of events in New England between 1621 and 1623. Although Winslow wrote to justify the colonists attack, he delayed a full representation of this violence by placing this account near the end of Good News. He first detailed the colonists concerns that various tribes were conspiring to attack them (including the Narragansetts, the Massachusetts, and the Wampanoags), and he included colonists observations of and encounters with Native peoples as evidence for these concerns. Meanwhile, his cure of Massasoit offered proof that the colonists had treated Native peoples with kindness and Christian charity. He also documented the colonists often desperate attempts to obtain food, including their process of planting their fields and their travels along the coast to trade with Natives for corn. After finally recounting the attack on the Massachusetts and its aftermath, Winslow concluded

Next page