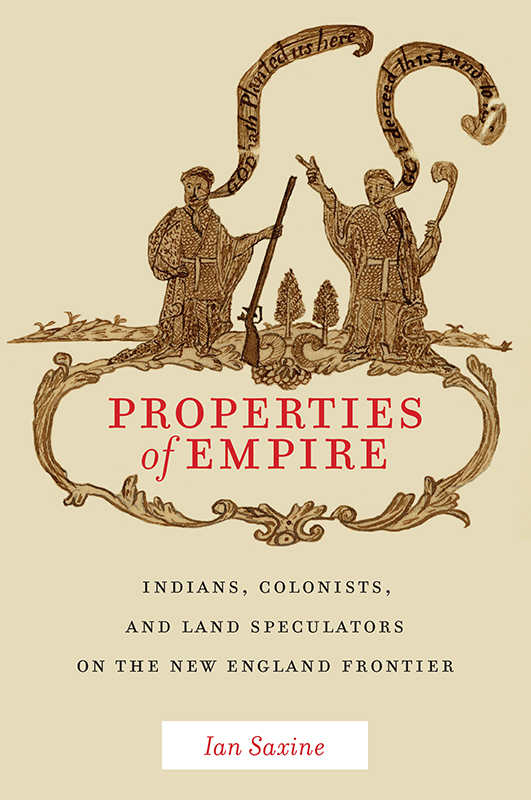

Properties of Empire

Early American Places is a collaborative project of the University of Georgia Press, New York University Press, Northern Illinois University Press, and the University of Nebraska Press. The series is supported by the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation. For more information, please visit www.earlyamericanplaces.org.

Advisory Board

Vincent Brown, Duke University

Andrew Cayton, Miami University

Cornelia Hughes Dayton, University of Connecticut

Nicole Eustace, New York University

Amy S. Greenberg, Pennsylvania State University

Ramn A. Gutirrez, University of Chicago

Peter Charles Hoffer, University of Georgia

Karen Ordahl Kupperman, New York University

Joshua Piker, College of William & Mary

Mark M. Smith, University of South Carolina

Rosemarie Zagarri, George Mason University

Properties of Empire

Indians, Colonists, and Land Speculators on the New England Frontier

Ian Saxine

New York University Press

NEW YORK

NEW YORK UNIVERSITY PRESS

New York

www.nyupress.org

2019 by New York University

All rights reserved

References to Internet websites (URLs) were accurate at the time of writing. Neither the author nor New York University Press is responsible for URLs that may have expired or changed since the manuscript was prepared.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Saxine, Ian, author.

Title: Properties of empire : Indians, colonists, and land speculators on the New England frontier / Ian Saxine.

Other titles: Early American places.

Description: New York : New York University Press, [2019] | Series: Early American places | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2018041757 | ISBN 9781479832125 (cl : alk. paper)

Subjects: LCSH: Abenaki IndiansLand tenureMaine. | Abenaki IndiansMaineTreaties. | Indians of North AmericaFirst contact with EuropeansMaine. | MaineHistoryColonial period, ca. 16001775.

Classification: LCC E99.A13 S29 2019 | DDC 974.004/9734dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018041757

For Mom, Dad, and Meghan

Contents

The Wabanakis were not a unitary political or even linguistic entity but rather a group of culturally and linguistically similar peoplesoften intermarrying with one anotherwho cooperated in trade, diplomacy, and war when it suited them. Around 1700, they formalized that relationship by forming the Wabanaki Confederacy. The various nations all spoke different branches of the Abenaki language, which is part of the larger Algonquian language group. These tribal affiliations remained fluid from a modern perspective, as overlapping kinship networks encouraged families to shift locations (and therefore, from a European viewpoint, tribal identity) due to political differences, marriage choices, or other reasons.

After a period of mid-seventeenth-century turbulence (discussed in chapter 2), the following major Wabanaki nations discussed in this book were sorted as follows, from west to east:

The Pigwackets lived primarily along the Saco River

The Amarascoggins lived along the Androscoggin River

The Kennebecs lived along the river of that same name

The Penobscots resided along a river of that same name

The Wulstukwiuks (also known as the Maliseet) lived along the St. John River. To the south, along a bay that bears their name, lived their close relatives, the Passamaquoddies, who, however, are not mentioned as a distinct people in most written records until the 1760s.

Other Abenaki speakers, many of whom were related to the above groups, lived in mission villages along the St. Lawrence River, called St. Francis (Odanak) and Becancour (Wowenock). Finally, the Mikmaqs, also members of the Wabanaki Confederacy, lived in present-day Nova Scotia and Cape Breton Island.

A few words about names, places, and dates are in order. While acknowledging the uses of the settler colonial framework, I agree with those scholars who have pointed out that calling the Europeans who arrived in the Dawnland settlers is misleading. The impact of the newcomers on the human and physical geography of the land was profoundly unsettling. Therefore, unless referring to Europeans settling in a long-established town in which they were invited to live, I call them what they were: colonists, newcomers, and sometimes trespassers or squatters. The newcomers hailed from across the British Isles, and also included French Huguenots, German Protestants, and a scattering of (usually) unfree Africans. When referring to them in general, I shall use the political label English before 1707, and British after the political union of England and Scotland that year. Most of the nomenclature normalized in historical accounts like this one comes from the colonizers, so I also use the Wabanaki word BostoniakBoston people to refer to the speculators originating in that place.

The term Wabanaki embraces both a constellation of linguistically and culturally similar groups and a political confederacy that formed sometime in the early or mid-eighteenth century (see glossary). Unfortunately, much remains unclear about the extent of the confederacys influence, so in this book, Wabanaki will be used as a general name for the Indigenous Algonquian-speaking inhabitants of present-day Maine and the Canadian Maritimes. Documentary evidence allows for more precise political nomenclature of the different Wabanaki tribes by the last quarter of the seventeenth century, and where possible, I use it. To avoid repetition, I also use the terms Native American, Indian, Indigenous, and, as an adjective, Native, interchangeably. When referring to individual Wabanakis, I have tried to use the names those people used for themselves.

Unless accompanied by the qualifier present-day, the terms Maine Acadia, and Nova Scotia refer only to the area within the physical extent of European control. I will call the rest of the Northeast what the people living there did: the Dawnland. I refer to the region between them as the eastern frontier (a glance at a map shows that Maine lies east of Massachusetts), the Maine or Dawnland frontier.

Except in cases where it would impede understanding (such as idiosyncratic abbreviations) I have left the spelling and style of the original sources unchanged. So, too, are the dates. Until 1752, British sources used the Julian calendar, which was by then eleven days behind the rest of Europe, which followed the Gregorian calendar. French sources are dated according to the Gregorian calendar throughout. Until 1752, the English began the New Year on March 25 on their Old Style calendar, before switching to the New Style on January 1, 1752. To prevent confusion, dates between January 1 and March 25 were often recorded as: February 2, 1733/4. In the text, all dates are adjusted for a New Style start of the year on January 1.

Properties of Empire

The one thing everyone agreed was that the 1736 encounter along the St. Georges River should not have happened. The Penobscot Indians who carried out the orderly eviction of frightened Scots-Irish colonists along the river in present-day Maine had never authorized the intrusion onto their lands. Led by Arexis, a sagamore (chief) fresh from a visit to Boston to complain about the trespassers, a considerable number of Indians... Sett up a Mark near the river, according to witnesses, and ordered all the colonists living above it to pull down their houses and leave.conflicts between European colonizers and Indigenous nations in North America over questions of landownership.

Next page