Copyright 2013 by the President and Fellows of Harvard College

All rights reserved

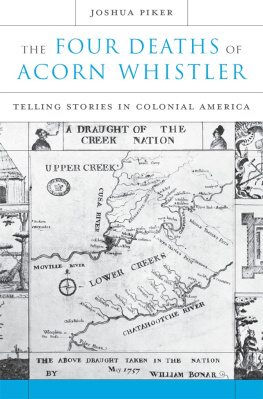

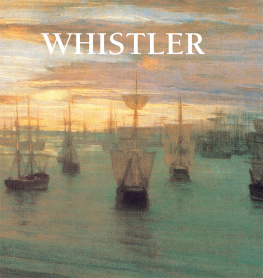

Cover illustration by William Bonar, May 1757

Cover design: Jill Breitbarth

The Library of Congress has catalogued the print edition of this book as follows:

Piker, Joshua Aaron.

The four deaths of Acorn Whistler : telling stories in colonial America / Joshua Piker.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-674-04686-3 (alk. paper)

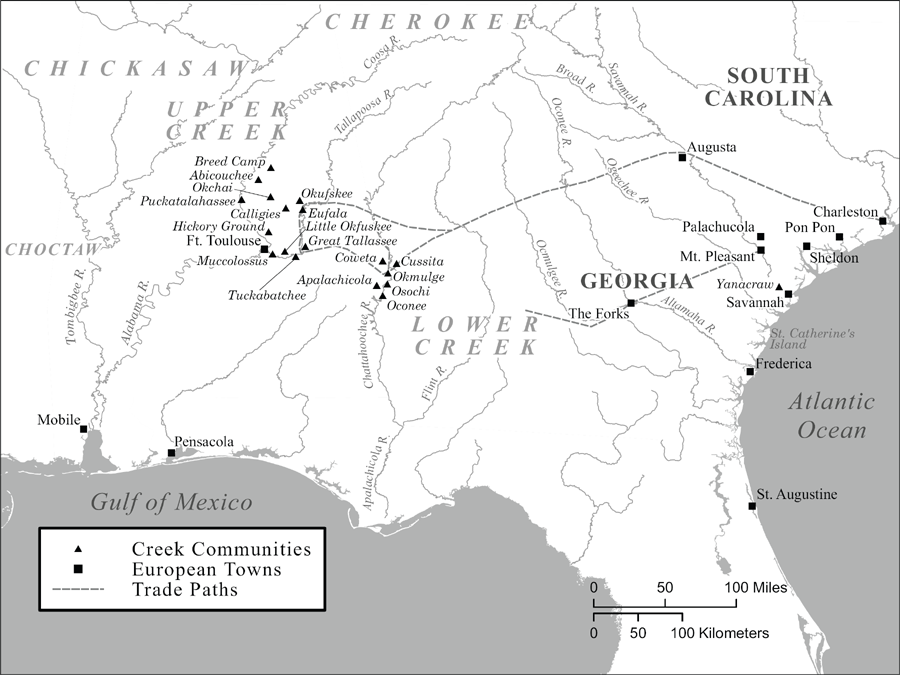

1. Acorn Whistler, d. 1752. 2. Acorn Whistler, d. 1752Death. 3. Creek IndiansKings and rulersBiography. 4. Cherokee IndiansViolence againstSouth CarolinaCharleston. 5. Southern StatesHistoryColonial period, ca. 16001775. 6. Great BritainColoniesAmericaAdministration. 7. Great BritainColoniesAmericaHistory18th century. I. Title.

E99.C9A28 2013

975.004'97385dc23

[B] 2012041388

THE DAYS VIOLENCE was unexpected and thus all the more shocking. About an hour before sunset, twenty-six Creeks fired on a party of twelve Cherokees. Initial reports that the Creeks have Killed every one of them or that Ten... are destroyed were wrong, but the carnage was still appalling. The attack clearly took the Cherokees by surprise. Three were killed at the first volley; the rest fled, one of which was killed in the Chace, and one taken Prisoner; at least two Cherokees were wounded. Later reports suggest that a fifth Cherokee died, and since there is no record of the prisoner ever being returned, he likely died as well. The numbers alone, moreover, cannot convey the brutality of the attack. A colonist who overheard the Creek barrage soon found the head of an Indian lying in the road and near the side of it saw the body of an Indian lying. Another colonist reported that one old Man had his Throat cut, while a second victim was shot thro the body, and his Head was cut off. All were scalpd. Twelve days afterward, one colonist labeled the incident a Skirmish, but most adopted the term South Carolina officials were using by 9 p.m. on April 1: murder.

As brutal as the attack was, however, its location was worse. This was no frontier dust-em-up, no ambush in the woods. Consider this: the Cherokee party was heading north, and the Creeks struck from behind, that is, from the south. If the Cherokees turned around at the sound of the Creeks guns, the last thing they might have seenbesides the onrushing Creeks, of coursewas the setting sun glinting off St. Philips Church, the most elegant Religious Edifice in British America.

And, in fact, the site of the attack was even more inflammatory than that. Think of those Cherokees facing north. When the Creeks attacked from the south and the Cherokees whirled around, did they turn to the right or the left? We cannot know, of course, but if they turned right, the first thing they might have seeneven before the Creekswas Belvedere, Governor Glens mansion. The attack took place less than half a mile from Your Excellencys gate, close enough that his gravely ill wife surely heard the shots. Perhaps the Cherokees were not speaking metaphorically when they claimed that their people were killed close by his Door? Glen, who arrived home after the attack, awoke very early the next morninghe had summoned his council to a 7 a.m. meetingto the news that there were several bodys of Dead Indians... lying on the Path. The dead Cherokees were almost certainly on the land of Artimus Elliott, Glens neighbor and a member of one of the colonys great rice-planting families. And the living? They were seen a mile or two north, on the Plantation of Joseph Wragg, a recently deceased eminent Merchant and longtime Member of his Majestys Council. This was an exclusive neighborhood in which to stage a massacre.

Worse than the violence of the attack, though, and worse than the incongruity of its location, was the fact that all involved had taken steps to avoid just this sort of incident. The Creeks and Cherokees were at war in 1752, but these Creeks had been warnedexplicitly, publicly, repeatedlynot to harm these Cherokees, and these Creeks had promisedexplicitly, publicly, repeatedlythat these Cherokees were safe. The Creek and Cherokee parties first met by accident in Charleston on March 29. The Creeks had arrived the day before and were encamped by the old School-House, where the Cherokees also intended to stay. This Accident almost produced very ill Consequence, according to Glen, for the Creeks seeing [the Cherokees] coming in imagined, I suppose, that they were coming to attack them and immediately took to their Arms. They were on the very Point of firing on the Cherokees when colonists intervened and with much ado... prevented... Bloodshed.

Two days later, on March 31, Glen met with the Creeks in the council chambers. He told them that the Cherokees are our Friends, so that the killing any of them in our Settlements is the same as killing any of us and a Thing we could not have put up with. The Creeks response reassured Glen: they had made Peace with them and... they had Eat and Drank with them and exchanged Blankets and Smoaked together and shaken Hands. Glen knew enough of Indian diplomacy to recognize that exchanging food and clothes and sharing tobacco represented a powerful statement of goodwill. In fine, he said, the Creeks looked upon the Cherokees as Brothers, and gave me the strongest Assurances that they would not touch them. Better yet, the Creeks promised to end the ongoing Creek-Cherokee war by making the Peace general, when they went home. Glen, in turn, told the Cherokees that they might depend on it, that the Creeks would not hurt them. Given the bloody events of the following afternoon, it is not hard to see why Glen would later begin a story about April 1, 1752, by remarking, But will you believe it, Friends and Brothers, or can you think it possible, what we are now to tell you?

The spokesman for the Creek partythe man who made all those pretty promiseswas Acorn Whistler, a head warrior from the Creek town of Little Okfuskee. Four and a half months later he was dead, executed by his fellow Creeks to make amends for the April 1 attack. Beginning immediately after his mid-August execution, Creeks and Britons talked incessantly about Acorn Whistlers guilt and the meaning of his death, a conversation that only ended in the summer of 1753 when a new crisis pushed the Acorn Whistler affair into the background. Prior to that point, though, stories about Acorn Whistler made the rounds in Creek country, the British colonies, and Great Britain.

People interested in ending the Creek-Cherokee war sought to use the April 1 attack as an example of warfares horrors and Acorn Whistlers execution as evidence of the Creek desire for peace. Other people, especially those personally connected to Acorn Whistler, instanced his execution as proof of their eagerness to resume relations with the groups victimized by the attack. Still others saw Acorn Whistlers execution as a chance not to renew old political ties but to create new ones, either by remaking their own society or by repositioning themselves within their societies hierarchies of wealth and status. Whatever their goals, though, all of these people found it necessary to tell stories about Acorn Whistlers death. And whatever their goals, no onenot even Acorn Whistlers kinsmen and townspeopletook it upon themselves to use their story to defend his innocence. Generations of historians, taking their cue from the unanimity among Acorn Whistlers contemporaries, have blamed him for the April 1 attack. In so doing, these scholars have unwittingly joined an old conversation, a centuries-long discussion that features the regular retelling of stories about Acorn Whistler. That these stories shape our histories more than two and a half centuries later tells us a great deal about their power, but the stories themselves tell us almost nothing about either what happened on April 1, 1752, or why Acorn Whistler had to die. There were, it turns out, many reasons to execute Acorn Whistler, but no one at the time truly believed that he died because he was responsible for the April 1 attack.