AMERICAN COLONIAL HISTORY

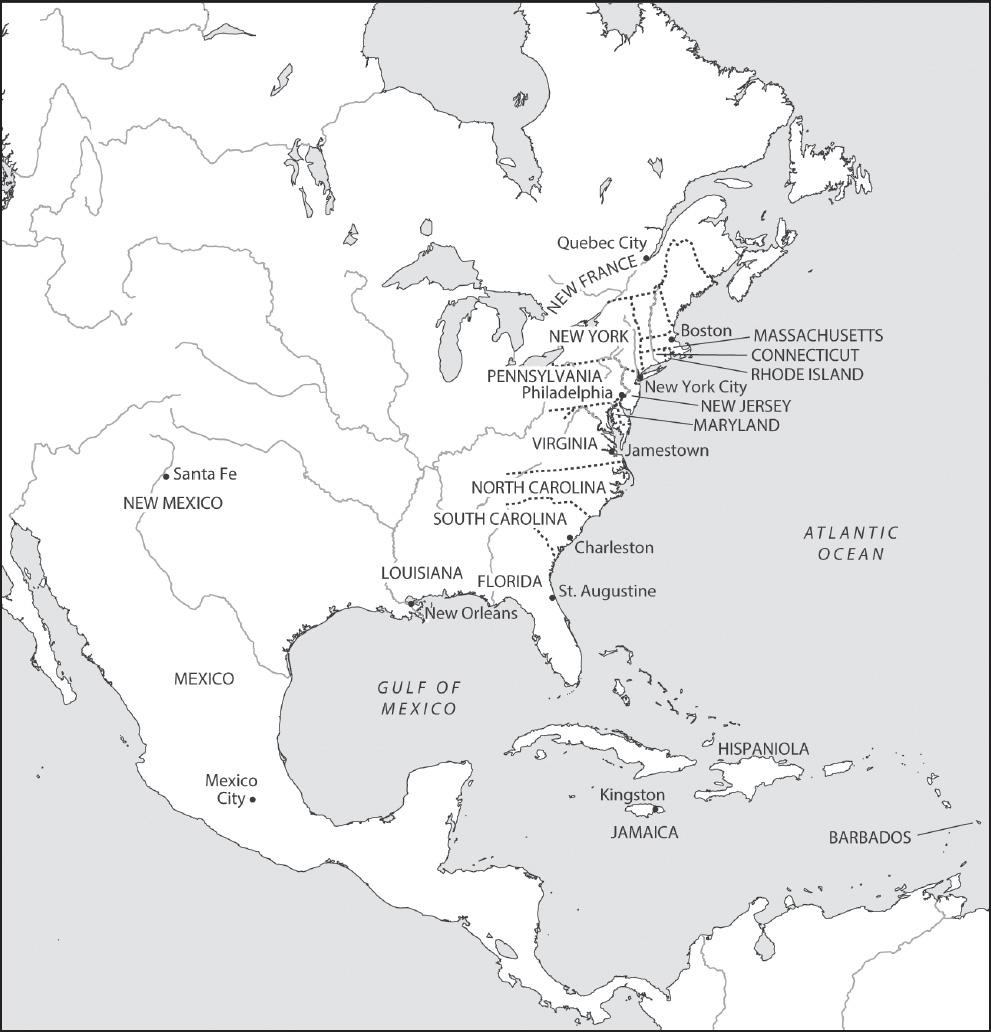

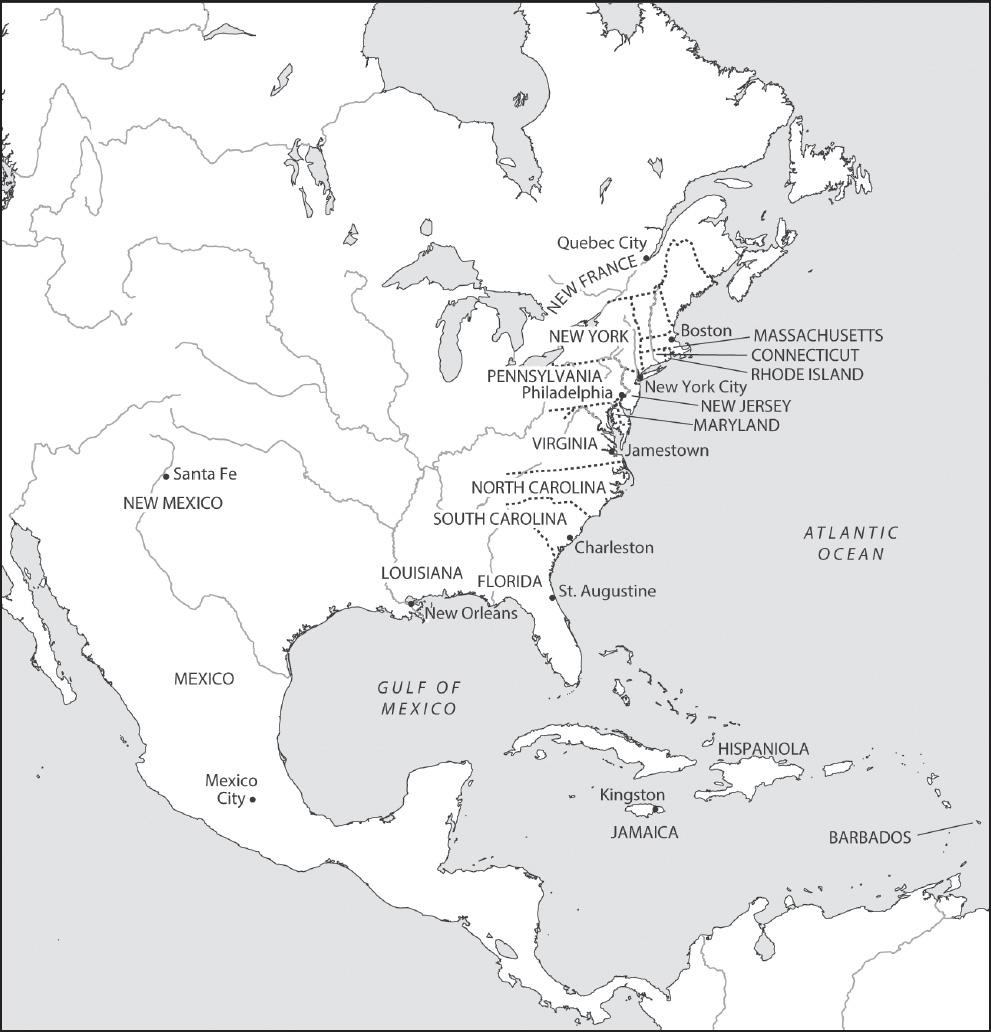

North America and the Caribbean, circa 1720. Map by Bill Nelson.

AMERICAN COLONIAL HISTORY

Clashing Cultures and Faiths

Thomas S. Kidd

Published with assistance from the foundation established in memory of Calvin Chapin of the Class of 1788, Yale College.

Copyright 2016 by Thomas S. Kidd.

All rights reserved.

This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publishers.

Yale University Press books may be purchased in quantity for educational, business, or promotional use. For information, please e-mail (U.K. office).

Set in Electra type by Integrated Publishing Solutions, Grand Rapids, Michigan.

Printed in the United States of America.

ISBN 978-0-300-18732-8 (paperback : alk. paper)

Library of Congress Control Number: 2015951238

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.481992 (Permanence of Paper).

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

INTRODUCTION

About 850 miles west of Jamestown, Virginia, a little south of the confluence of the Missouri and Mississippi rivers, stands the site of the city of Cahokia. Nine hundred years ago it was the largest city in the region that would become the United States. Cahokia was at least as big as London and Rome during the same period. By the twelfth century C.E., about twenty thousand people lived at Cahokia, which contained 120 ceremonial mounds, some of immense scope. The city spread over five square miles.

Earlier settlements, including a smaller one at Cahokia, had dotted the rich Mississippi river bottoms in the area before the eleventh century, but something changed dramatically to create the new city. The catalyst may have come from a spectacular astronomical phenomenon, a supernova. On July 4, 1054, people around the globe observed what appeared as a daytime star, four times as bright as Venus, resulting from the explosion of a star in its death throes. This kind of brilliant eruption is exceedingly rare the last observed supernova in the Milky Way happened in 1604.

From China to America, observers noted and etched the phenomenon. At Chaco Canyon, in present-day New Mexico, an artist painted an image of the supernova on sandstone cliffs. The residents of Chaco Canyon also began construction around 1054 on a large new kiva, a below-ground ceremonial building frequently seen at southwestern Indian dwellings.

Around the time of the supernova, the old village at Cahokia virtually vanished. Inhabitants replaced it with a larger complex of houses, plazas, and earthen pyramids. The city surrounded a vast grand plaza, topped at its north end by an astounding clay pyramid, which by the year 1200 towered a hundred feet over the plaza below, making it the third largest structure of its kind in the New World, surpassed only by two pyramids in Mexico. One of these was the Pyramid of the Sun at Teotihuacn, a much older city, which at its height in the fifth century C.E. was one of the largest in the world, with perhaps 150,000 residents.

Cahokias rapid ascent was led by powerful rulers and created deep social divides. The mounds there have yielded evidence of ritual burial and human sacrifice. One burial temple held the skeleton of a man who was interred on top of a blanket adorned with some twenty thousand shell beads. Close to his body lay four men who had been dismembered. In another nearby pit lay the carefully positioned bodies of fifty-three young women, all of whom presumably died during the same event. Other Cahokia-area excavations have produced hundreds of bodies that display signs of ceremonial killings. Archaeologists have surmised that these people may have fallen victim to rituals surrounding the death of a ruler, perhaps so he could have servants or companions to accompany him into the next life. Or perhaps elites meant to communicate that lowly Cahokians lived only at the rulers will.

The silent testimonies of these bodies point us to both social and spiritual beliefs at Cahokia. The spiritual world inspired rituals, and influenced even the positioning of mounds and buildings, many of which aligned with vernal and autumnal equinoxes. Many Native Americans were profoundly religious, even if their faith was not as focused on doctrines as that of many Europeans, who would begin arriving in the Americas some three hundred years after Cahokias heyday.

Things changed often in Native Americans worlds prior to Columbus. Just as quickly as the city of Cahokia rose, it fell. By the mid-1300s the great complex was essentially abandoned. Cahokias elite mound builders were probably victims of their own success, as their urban concentration made it difficult to supply the towns needs. Warfare, disease, and political controversy may have also contributed to Cahokias demise. In any case, when Europeans began visiting the area in the seventeenth century, the Illini Indians living there did not know much about great Cahokia, its presence signaled only by overgrown mounds dotting the landscape. The mounds were the works of their forefathers, some Illini told Revolutionary War leader George Rogers Clark, ancestors who were formerly as numerous as the trees in the woods. Adding to a long list of European-American misnomers, French settlers called the ruined city Cahokia, after one of the Illinis major clans.

Religion indisputably inspired the first European settlement at Cahokia, which arrived with French Catholic missionaries in 1699. The Seminary of Foreign

Few Cahokia Indians converted at the mission, and anger against the French grew. In spring 1733 the priests and French laypeople fled from the mission under the cover of darkness, having heard that the Indians intended to surprise and kill them. (Only three years earlier, local Indians had done this at Natchez, farther down the Mississippi, killing more than two hundred French men, women, and children, and capturing some three hundred black slaves.) Nothing came of the Cahokia panic, but French officials did require the Cahokia Indians to settle further from the French village. They went nine miles away, to the base of the largest Cahokia mound (Monks Mound, named later for a group of Trappist monks who farmed it in the early nineteenth century.) There the French established a new mission station for them.

Resentment over land did not just sour French and Cahokian relations; they embittered Fox and Cahokian Indians toward one another, too. This feud culminated in a devastating Fox raid on Cahokia in 1752. Christianized Cahokias were attending a Corpus Christi feast at the nearby Fort de Chartres when the attack came. Many Cahokias died or were taken captive. The raid set the stage for the eventual extinction of the Cahokias, who merged with the Peorias. The U.S. government would relocate the Peorias to Oklahoma following the Civil War.

War and diplomacy imposed a newif largely nominal order on Cahokia in 1763. The east bank of the Mississippi became British. The French loss in the Seven Years War, and its concluding peace agreement at Paris in 1763, assigned eastern North America to the British. Under the terms of a secret treaty struck in

Next page