Peaceable Kingdom Lost

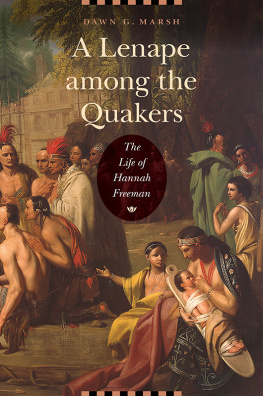

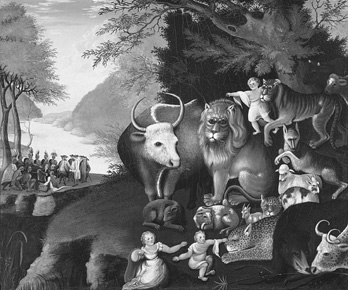

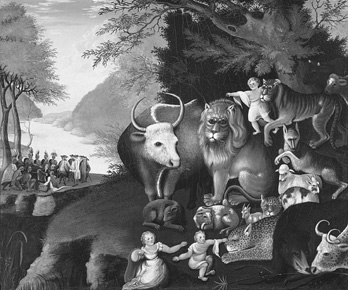

Peaceable Kingdom. The Quaker artist Edward Hicks (17801849) produced more than 100 versions of this allegorical painting based on a passage from Isaiah 11:69: The wolf also shall dwell with the lamb, and the leopard shall lie down with the kid; and the calf and the young lion and the fatling together; and a little child shall lead them. Hicks interpreted Pennsylvanias early history through this biblical allegory, including in most versions of the painting a vignette of William Penns legendary meeting with the Delawares at Shackamaxon in 1682, adapted from a popular work by Benjamin West (see page 18). Oil on canvas, 29-5/16 35-1/2 in., 1834. Gift of Edgar William and Bernice Chrysler Garbisch. Courtesy National Gallery.

PEACEABLE KINGDOM LOST

The Paxton Boys and the Destruction of William Penns Holy Experiment

KEVIN KENNY

Oxford University Press, Inc., publishes works that further Oxford Universitys objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education.

Oxford New York

Auckland Cape Town Dar es Salaam Hong Kong Karachi Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Nairobi New Delhi Shanghai Taipei Toronto

With offices in

Argentina Austria Brazil Chile Czech Republic France Greece Guatemala Hungary Italy Japan Poland Portugal Singapore South Korea Switzerland Thailand Turkey Ukraine Vietnam

Copyright 2009 by Kevin Kenny

Published by Oxford University Press, Inc. 198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016

www.oup.com

Oxford is a registered trademark of Oxford University Press

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of Oxford University Press.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Kenny, Kevin, 1960

Peaceable kingdom lost : the Paxton Boys and the destruction of

William Penns holy experiment / Kevin Kenny.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-19-533150-9 1. PennsylvaniaHistoryColonial period, ca. 16001775. 2. Paxton Boys. 3. PennsylvaniaRace relationsHistory18th century.

4. VigilantesPennsylvaniaHistory18th century. 5. Indians of North AmericaPennsylvaniaHistory18th century. 6. Culture conflictPennsylvaniaHistory. 7. Penn, William, 16441718Philosophy. I. Title.

F152.K29 2009 323.1197074809033dc22 2008038445

1 3 5 7 9 8 6 4 2

Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper

For Owen

CONTENTS

ONE

FALSE DAWN

TWO

THEATRE OF BLOODSHED AND RAPINE

THREE

ZEALOTS

FOUR

A WAR OF WORDS

FIVE

UNRAVELING

Peaceable Kingdom Lost

INTRODUCTION

The Paxton Boys struck Conestoga Indiantown at dawn on December 14, 1763. Fifty-seven Men, from some of our Frontier Townships, who had projected the Destruction of this little Commonwealth, Benjamin Franklin wrote in his Narrative of the Late Massacres in Lancaster County, came, all well-mounted, and armed with Firelocks, Hangers [a kind of short sword] and Hatchets, having travelled through the Country in the Night, to Conestogoe Manor. Only six Indians were in the town at the time, the rest being out among the neighbouring White People, some to sell the Baskets, Brooms and Bowls they manufactured. The Paxton Boys, frontier militiamen on an unauthorized expedition, killed these six and burned their settlement to the ground.

The Conestoga Indians lived on a 500-acre tract near the town of Lancaster, which William Penn had set aside for them seventy years earlier. By 1763 only twenty Conestogas were living thereseven men, five women, and eight children. They survived by raising a little corn, begging at local farms, soliciting food and clothing from the provincial government, and selling their homemade brooms and baskets. Rhoda Barber, born three years after the Paxton Boy massacres, recalled in old age what her family had told her about the Conestogas. They were entirely peaceable, she wrote, and seemd as much afraid of the other Indians as the whites were. Her older brother and sisters used to spend whole days with them and were so attached to them they could not bear to hear them refusd anything they askd for. The Indians often spent the night by the kitchen fire of the farms round about and were much attached to the white people, calling their children after their favorite neighbours.

Local magistrates removed the remaining fourteen Conestoga Indians to the Lancaster workhouse for their safety, but on December 27 the Paxton Boys rode into that town and finished the job they had started two weeks earlier.

Inspired by Quaker principles of compassion and tolerance, Penn saw his colony as a holy experiment in which Christians and Indians could live together in harmony. He referred to this ideal society as the Peaceable Kingdom. The nineteenth-century Quaker artist Edward Hicks produced a series of allegorical paintings of the Peaceable Kingdom, juxtaposing a theme from the Book of Isaiah with Penns meetings with the Delaware Indians. In pursuit of this harmonious vision, Penn treated the Indians in his province with unusual respect and decency. The Conestogas called him Onas and the Delawares knew him as Miquon; both words mean feather, referring to the mysterious new quill pen wielded at treaty negotiations. The Conestogas conferred the name Onas on Penns children and grandchildren as well, in the hope that they might embody his benign spirit.

Yet for all Penns decency, his holy experiment rested firmly on colonialist foundations. There would have been no Pennsylvania, after all, had he not received a gift of 29 million acres from Charles II in 1681a gift that made him the largest individual landlord in the British Empire. Within his immense charter, Penn purchased land from Indians fairly and openly. But he did not do so simply out of benevolence. He needed to free the land of prior titles so that he could sell it to settlers and begin to recoup the vast expenses incurred in setting up his colony. As an English landlord, Penn naturally believed that land could be privately owned by individuals and that its occupants could permanently relinquish their title in return for money or goods. This idea ran counter to the ethos of Pennsylvanias Indians, who held their land in tribal trusts rather than as individuals and used it to sustain life rather than to make a profit. Indians often sold the same piece of land on multiple occasions, transferring rights of use and occupancy rather than absolute ownership. Penn wanted harmony with Indians, but he also needed to own their land outright. His holy experiment, therefore, never properly took root. But it left an

William Penns holy experiment, already in decline by the time of his death in 1718, disintegrated gradually over the next few decades and collapsed during the Indian wars of the 1750s and 1760s. His son Thomas reverted to Anglicanism, casting off the Quaker faith that sustained his fathers humane benevolence. Thomas Penn and his brothers continued to negotiate with Indians, but, unhampered by religious scruples, they did not hesitate to use fraud and intimidation. In 1737 they swindled the Delawares out of a tract of land almost as big as Rhode Island in a sordid transaction known as the Walking Purchase. Although William Penns legacy ensured that relations with Indians were at first more harmonious in Pennsylvania than in other American colonies, the eventual outcome was everywhere the same: expropriation, conquest, and extermination. The colony moved from the false dawn of Penns holy experiment, through the avarice and subterfuge of his sons, to the carnage of the French and Indian War and the ruthless brutality of the Paxton Boys. By the end of 1763, with the annihilation of the Conestoga Indians, what was left of the Peaceable Kingdom had broken down entirely.

Next page