1. William Segar portrait of Ralegh, 1598

O n his third imprisonment in the Tower of London, an inventory was taken of such things as were found on the body of Sir Walter Rawleigh, Knycht, the 15 day of August 1618.

Ralegh might have been wearing a coat tailored of the New Draperies, the stylish, soft worsted wool used in expensive English coats, a wool suitable for a summer day in London. The coat would have had huge pockets to accommodate the myriad items recorded in the inventory.

Ralegh no longer introduced to the court new fashions as he had done thirty years earlier, but he still knew how to dress the part of Englands most famous knight. In the words of one scholar, Ralegh epitomized Renaissance self-fashioninghe created images of himself to present to the world. If anything, this understates how much Ralegh truly imagined about his world. Imagination was a powerful, creative force in his life. He used poetry, prose, music, conversation, and storytelling to createor re-createpeoples and places, imaginary, legendary, and mythical, that were as real to him as the peoples and places he knew firsthand. He imagined himself a great colonizer of overseas lands who would earn fame on a par with Columbus and Corts.

His pockets full of personal treasures and mementos, Ralegh also carried ores into prison, where he would assess whether they contained silver or gold in the laboratory he had built during his second imprisonment. In this laboratory, he also produced cordials to heal the sick: he carried an ounce of ambergris, the gray, waxy substance secreted by the sperm whale, highly valued for treating an array of ailments. And he wrote his wife to bring him additional ingredients. Ralegh also carried in his pocket a spleen stone obtained in Guiana more than twenty years earlier and likely used to create a curative tea. The kings officials confiscated most everything he brought except for the ambergris and spleen stone.

Ralegh spent much of his life studying, planning, preparing, and then producing. As he sailed the ocean blue, he reputedly brought with him a parcel of books. In prison, he amassed over five hundred volumes in multiple languages, including Latin, Greek, French, and Spanish. His interests ranged from geopolitics to alchemy. In the British Library can be found his handwritten recipe for barreling beef. He wrote about royal marriages, warrior women, and numerous other subjects. And he often worked under difficult circumstances. During his second imprisonment in the Tower of London, he gained international fame for the cordials he produced in the laboratory, and he penned the most renowned history written by an Englishman in the seventeenth century.

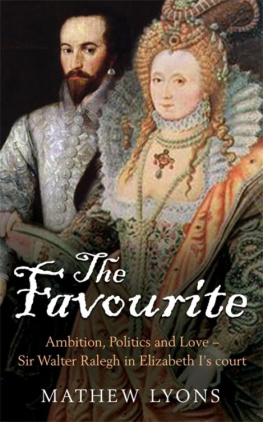

Ralegh not only became expert in myriad fields but also lived a physically active life of public service. He frequently recruited men to serve on sea and land, built and inspected fortifications, captained ships, and led men into battle. He was an adventurerin the original meaning of the term, he ventured his life and his capital on numerous enterprises in the Atlantic World. Famously, he searched for El Dorado, the legendary city of gold, hoping to add the Empire of Guiana and Peru to Queen Elizabeth Is empire. As her favorite, he became one of the most despised men in England, and also one of its greatest heroes. The painting on page xiv shows Ralegh in one of his typical outfits that could carry all the many items in the inventory, and in the top left it depicts the city of Cdiz. Ralegh was the hero of the Battle of Cdiz in 1596, the cane in his right hand a reminder of the grave leg wound he received there.

In 1618, when Ralegh entered the Tower of London as prisoner of King James I of England, he was much admired as the last of Queen Elizabeths famous knights. Today he is remembered for the apocryphal story of how he laid his cloak over the mud so Elizabeth should not dirty her shoesthe courtier par excellence. Dashing, witty, and handsome, he earned the queens love and respect. She permitted him monopoly rights to found Englands first colony in America, which he named Virginia in her honor.

Raleghs pockets were filled with items reflective of his life as the foremost English colonizer of the sixteenth century. He had not only held sole patent from Elizabeth to colonize in America but also received from her the largest chunk of land in the Munster Plantation, the most significant sixteenth-century English colonization project in Ireland. And he had pursued a thirty-year effort to colonize in South America. He stood at the center of all the major colonization projects of Elizabeths reign, yet historians ignore their overlap and instead focus on his North American endeavors, giving scant attention to Ireland and South America. At exactly the same time Ralegh directed English colonization of North America, he undertook colonization of Ireland and sent people to South America to prepare for English colonization there. And his interests overseas were not confined to colonization. Ralegh organized and participated in naval and pirating expeditions, helped open new Atlantic trade routes, and played a significant role in Englands rise as a maritime power.