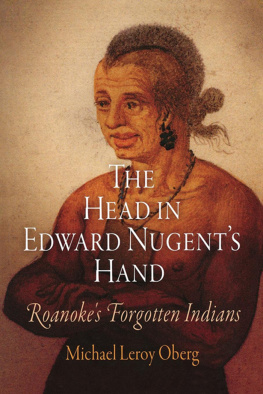

Sir Walter Raleghs adventurers were instructed to keep journals of their exploits in the New World. Many of these priceless manuscripts were lost or mislaid over time, and have only been rediscovered and printed in recent years.

I owe a debt of gratitude to Professor David Beers Quinn, who has devoted a lifetimes study to Raleghs colonies. Without his magnificent Roanoke Voyages a collection of almost every surviving manuscriptthis book could not have been written. I am also grateful to him for kindly inviting me to his Liverpool home to share his encyclopaedic knowledge.

I received much help from experts in America. I am particularly grateful to Tom Shields, editor of the Roanoke Colonies Research Newsletter, for generously sparing time to show me Roanoke Island. Thank you also to John Gillikin and Steve Harrison of the Fort Raleigh National Historic Site, to the staff at the Outer Banks History Center, and to librarians at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Thank you to William Kelso, chief archaeologist of the Jamestown Rediscovery Project, for guiding me around the recent excavations, and to curator Beverly Straube for allowing me access to the remarkable artefacts that have been unearthed.

In London, I am deeply grateful to Paul Whyles for poring over the manuscript at short notice and suggesting many much-needed changes. Thank you also to Frank Barrett, Wendy Driver, Simon Heptinstall, Roland Philipps, Maggie Noach, Jill Hughes, and John Glusman; to Mrs. Angela Down, owner of Hayes Barton, Raleghs childhood home; and to the staffs of the British Library and the Institute of Historical Research. A particular thank you to the ever helpful librarians of the London Library.

Lastly, I wish to thank Alexandra for her support and encouragement, and Madeleine and Hlose for their tea-break entertainments.

More than three decades had passed since there had been any news of the settlers left behind on Roanoke, and much had changed in the intervening years. England was now a great sea power, and was respected throughout Europea cause of celebration for all the captains and mariners who had challenged Spains self-proclaimed rule over the oceans. But Queen Elizabeths brilliant reign was fast fading into historya glittering epoch that was already being spoken of as a golden age.

Yet two of the greatest Elizabethans, Sir Walter Ralegh and Thomas Harriot, were still alive. Stiff-jointed and withered by age, these doughty champions of American colonisation retained an immense pride in the role they had played in the establishment of a settlement over the seas. The lost colonists were the only reminder that not all had gone according to plan, that there had been much disaster and mishap on the way. They also provided a timely warning that Raleghs bold and audacious experiment had two endings: one happy and one distinctly tragic.

John Whites settlers were not the only ones to be lost on American soil. Three men had been left behind when Sir Francis Drake evacuated Ralph Lanes colonists in 1586. Sir Richard Grenvillehad deposited a further fifteen men on Roanoke as a holding party in the same year. Some of these had been killed, including Master Coffin and one of his deputies, but that still left a total of at least 123 English men, women, and children unaccounted forlost in the unmapped wilderness of America. The fate of these unfortunate souls had long fired the imagination of a curious England, and there were manyeven in 1618who believed that some had survived their thirty-two-year ordeal.

Four centuries after they were lost, their fate continues to fascinate and intrigue. Did Whites settlers really move to Croatoan Island? Were they clubbed to death or starved into submission? Or did they settle and intermarry with the local Indian tribes?

Their disappearance has been the subject of endless speculation, and numerous theories have been advanced. Although many have seemed initially plausible, almost all have rested upon slender evidence that has later been proved false.

The most exciting proof of the survival of the lost colony surfaced in the latter part of the nineteenth century, when a North Carolinian enthusiast, Hamilton McMillan, claimed to have discovered the descendants of Whites settlers. McMillan had become intrigued by a group of red-bones, or mixed-blood Indians, living in the southeastern corner of the state. His research into their archaic language led to the hypothesis that they used an Elizabethan dialect similar to that spoken by Whites colonists. This seemed plausible, and many were inclined to believe him. But when linguistic experts were called in to conduct a detailed investigation into McMillans work, they found it to be blighted with errors. His English red-bones turned out to be nothing more than a figment of his own fantasy.

In the 1930s an exciting new piece of evidence came to light. A chiselled stone was unearthed which bore Eleanor Dares initials, as well as a lengthy inscription written in Elizabethan English. This revealed the surprising news that the colonists had indeed movedtheir settlementnot to Croatoan Island, but to the banks of the Chowan River. At first, there was great excitement at the find, but disappointment set in when mistakes were found in the Elizabethan inscription. Soon after, scientific tests conclusively proved that the stone had been carved in the recent past.

The next theory, promulgated by Robert E. Betts in Londons Cornhill Magazine , was that a Spanish military force had located and killed the lost colonists soon after Whites departure. But this, too, was quickly disproved when new evidence was discovered in Spains archives in Seville.

One by one the claims and theories fell apart, and the riddle of the lost colonists remained as mysterious and intriguing as ever. Too many theoreticians looked for evidence among the records of Raleghs Roanoke enterprise, and neglected the diaries and journals kept by the early Jamestown settlersthe very men who actually went in search of the lost colonists. It was they who scoured the forests; they who quizzed the Indians; and they who were in the best position to establish the truth. Although their eyewitness accounts are not supported by concrete proofonly a spectacular archaeological discovery will be able to supply thattheir findings are as compelling as they are exciting, and offer the only plausible hypothesis as to what happened to John Whites lost colonists.

The first clues of their whereabouts were found by John White on his 1590 search-and-rescue mission. He determined that they no longer remained on Roanoke, but brought back little more than supposition as to where they might have gone. There was the word CROATOAN carved into a treesuggesting that the colonists had headed to Manteos island homeand there was Whites perplexing statement that the colonists had previously told him of their intention to move 50 miles further up into the maine. Neither of these facts made much sense: Croatoanthe first optionwas little more than a giant spit of sand, on which its native inhabitants found it hard to produce enough crops to feed themselves. When White hadvisited the island in 1587, their first concern was that his emptybellied men would eat into their precious food stocks, for that they had but little.

The second choice was only slightly more plausible. It would have been hard, though not impossible, for 107 colonists to transport themselves to another location without a much larger vessel than the pinnace that they had at their disposal. Not only did they need to be moved, there were also their personal belongingswhich amounted to perhaps 120 large wooden sea chestsas well as a significant quantity of weaponry, tools, and general supplies. To transport such a stockpile of material would have taken three or four journeys, even allowing for the fact that the heavy weaponry had been left behind on Roanoke.