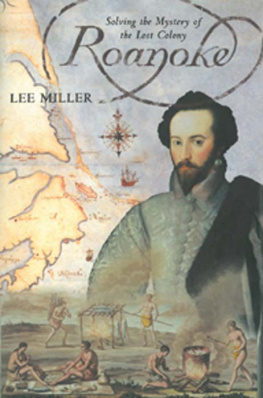

Copyright 2000, 2011 by Lee Miller

All Rights Reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner without the express written consent of the publisher, except in the case of brief excerpts in critical reviews or articles. All inquiries should be addressed to Arcade Publishing, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018.

Arcade Publishing books may be purchased in bulk at special discounts for sales promotion, corporate gifts, fund-raising, or educational purposes. Special editions can also be created to specifications. For details, contact the Special Sales Department, Arcade Publishing, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018 or arcade@skyhorsepublishing.com.

Arcade Publishing is a registered trademark of Skyhorse Publishing, Inc., a Delaware corporation.

First published in Great Britain by Jonathan Cape

Visit our website at www.arcadepub.com.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available on file.

ISBN: 978-1-61145-331-7

TO MY PARENTS

WITH LOVE

CONTENTS

PREFACE

When I first began work on this book, I intended to write a straightforward history, whose ending included a mysterious disappearance that I hoped to solve. However, I was wholly unprepared for what very rapidly emerged as three mysteries in one. It was apparent that I was dealing with a hugely complex sequence of events that did not all begin the moment 116 men, women, and children landed on Roanoke Island, subsequently to disappear without a trace. Their story was vastly more than that.

Sir Walter Raleigh said that although a princes business is seldom hidden from some of those many eyes which pry both into them, and into such as live about them, they yet sometimesconceal the truth from all reports. What is true of princes is also true of others, and such concealment was certainly the case with the Lost Colony tragedy. Evidence indicates that the truth about the colonists fate was known, although misleading official statements were passed off in its place.

One great flaw in the writing of history is that we often tend to accept easy explanations of events. The job of an historian, said Raleigh, being full of so many things to weary it, may well be excused, when finding apparent cause enough of things done, it forbeareth to make further search. So comes it many times to pass, that great fires, which consume whole houses or towns, begin with a few straws that are wasted or not seen.

This was true here. There was something wrong with the Lost Colony story as it had been told. It went like this: Sir Walter Raleigh obtained a royal patent from Queen Elizabeth I for rights to settle North America. In the spring of 1584, he launched an exploratory expedition under Captains Philip Amadas and Arthur Barlowe which located Roanoke Island before returning home that autumn. The following year, he raised a military expedition headed by Sir Richard Grenville which reached Roanoke Island in the summer, built a fort there, and remained in it until the spring of 1586. Finally, in 1587, Raleigh sent a colony of men, women, and children to the Chesapeake Bay with their governor, John White, with instructions to call at Roanoke on the way. For some reason Whites ineptitude as a leader, his preference for Roanoke Island, or unruly mariners they went no farther than Roanoke and settled there in the abandoned military fort. Already short of supplies, White reluctantly returned to England with the transport ships. Unfortunately, his arrival in London coincided with the coming of the Spanish Armada. With England at war, he was unable to relieve the colony until 1590. When he finally did return to Roanoke, the colonists had vanished. Years later, Jamestown officials reported that the Lost Colonists had been murdered by the Powhatan Indians of Virginia.

This story is solidly backed by four hundred years of retelling. It is a myth created to explain glaring inconsistencies, to smooth out the rough edges of unanswered questions. Without the myth, none of the circumstances make sense. Why did John White take his colonists to Roanoke, and not to the Chesapeake Bay as planned? Why did he return to England? If not to fetch supplies, then why did he leave his colony? If not the war, then why didnt he come back? And if the Powhatan didnt kill them, then where were the Lost Colonists? The moment the accepted story is pulled away, the questions leap out, demanding answers. The moment the questions are asked, the accepted story no longer fits.

There is something unsettling about a mystery. When it involves tragedy, it is doubly so. When that tragedy is the loss of 116 people and their inexplicable disappearance, the need to find answers is compelling. When history said there was nothing left to tell, we had only scratched the surface of the puzzle. It is still possible, at this late date, to wring out the facts, to squeeze out more information, to uncover that which it was never intended we should uncover. To learn the truth. To solve a mystery.

Some will find it jarring. Raleigh himself did not write his own side of the story, though perhaps he gave us his reasons when he wrote, / know that it will be said by many, that I might have been more pleasing to the reader if I had written the story of mine own times. To this I answer that whosoevershall follow truth too near the heels, it may happily strike out his teeth.

A note about methodology is in order. The quotes used in this book date from the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. They are interspersed within the text in a way that was intended to be as seamless as possible, but are distinguished from it by being rendered in italics. For ease in reading and to maintain a consistent style, spellings and punctuation have been modernized with the exception of personal names which have been modernized or not according to context and Indian names, which I left as they appeared in the original.

The story of the Lost Colony is Americas oldest mystery. To tell it properly, I felt that it had to be told as a mystery, not simply as a chronological history. This allows the reader to approach the material as a series of questions, each one leading to the next, in order to preserve both a sense of discovery and a sense of the complexity of the data, which at first sight seems baffling, inexplicable, and contradictory.

Contrary to the impression generally given, clues to the Lost Colonists whereabouts abound, although they have never been given equal value in any previous treatment of the subject. As a consequence, the mystery has not been solved. The single most important question surrounding the Lost Colonists is: Why were they left on Roanoke Island? From this question all else follows: Who was responsible for this, and why? What were the initial reports filtering into London? If the colony was in trouble, why did its governor, John White, abandon it and return to England? Do we know something about his background, or about the colonists themselves, that could explain what was happening? What does John Whites own account reveal of the problem? What were the conditions on Roanoke that would explain the colonists disappearance? What of the conflicting reports from Jamestown of Lost Colony sightings?

Question after question drives us back in time from effect to cause until we finally reach the first plateau: Why were the colonists lost? Only when we understand this, and the danger posed by Roanoke Island and its environs, can we move forward to trace what happened after their disappearance. I chose to tell this story, then, as a series of discoveries generated by key questions. The result is not a traditional history format. If it conveys, as I hope, anything of the tension and drama of the story itself, then I have succeeded.