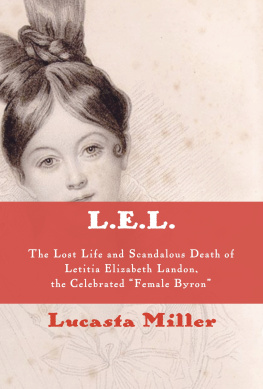

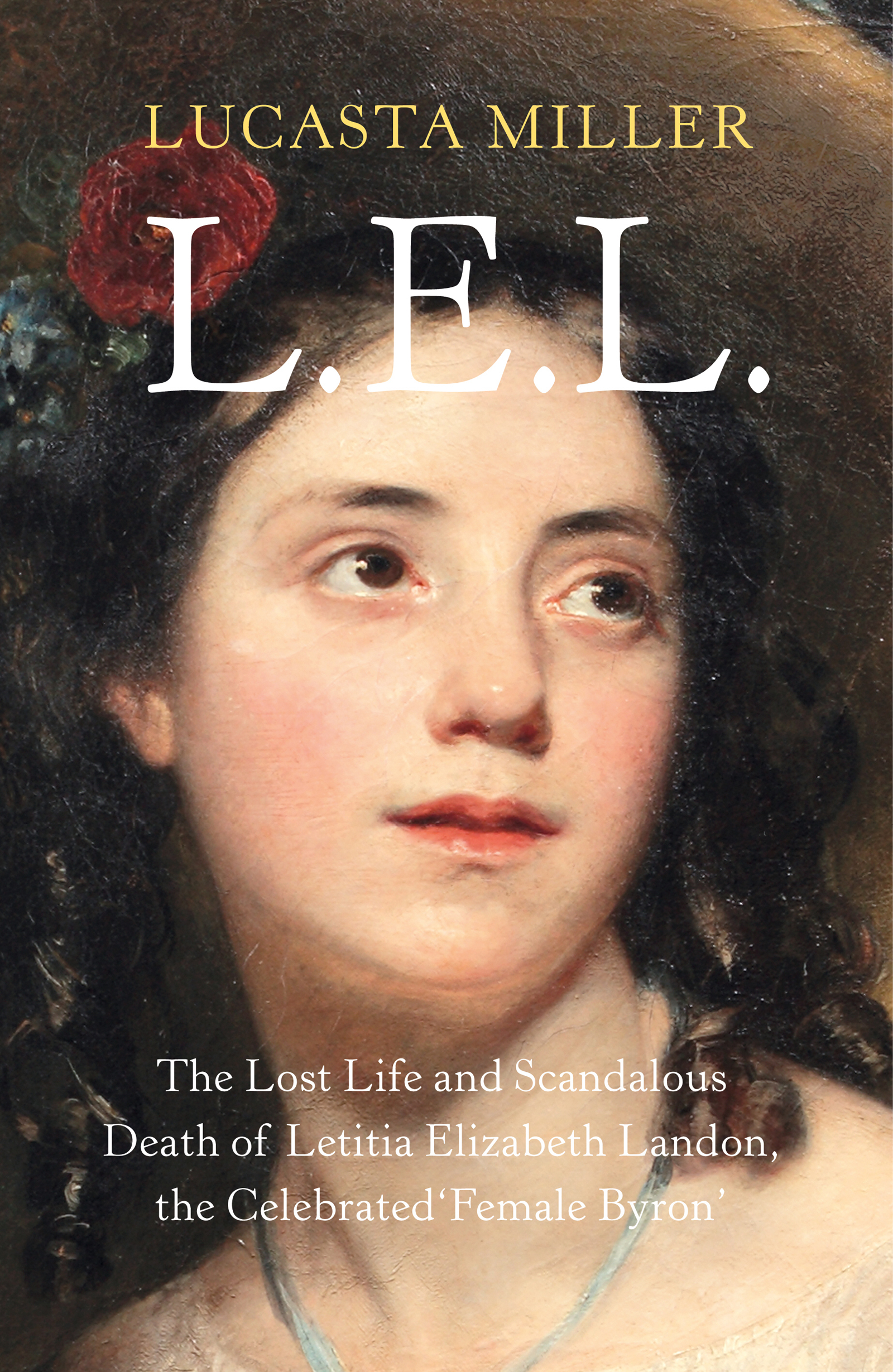

L.E.L.

The Lost Life and Scandalous Death of

Letitia Elizabeth Landon

the Celebrated Female Byron

LUCASTA MILLER

Contents

About the Author

Dr Lucasta Miller is the author of The Bront Myth and a literary journalist whose work has appeared in a wide number of publications, especially the Guardian. She is Beaufort Visiting Fellow at Lady Margaret Hall, Oxford 20152016 and lives in London with the tenor Ian Bostridge and their two children.

BY THE SAME AUTHOR

The Bront Myth

For I, O, and O

Forget heroin. Just try giving up irony, the deep-down need to mean two things at once, to be in two places at once, not to be there for the catastrophe of a fixed meaning.

Edward St Aubyn

Preface

This book is about a poet who disappeared: about a woman who pursued her career in a blaze of publicity while leading a secret life that eventually destroyed her, and who left a such a legacy of lies and evasion that her true story can only now be told.

Letitia Elizabeth Landon, who published under her initials, L.E.L., was fted as the female Byron during the 1820s. But after she was found dead in 1838, in West Africa of all places and in suspicious circumstances, the early Victorian publishing industry closed ranks to erase what they had come to see as her shameful history. Her literary reputation declined. She was left on the margins, surrounded by an aura of mystery and occlusion, her work routinely misunderstood.

Over the past couple of decades, she has finally begun to attract more interest. Her work has begun to appear in anthologies of nineteenth-century verse and to be analysed in scholarly articles. She has even begun to feature in a minor way on many university English literature syllabuses. At the same time, biographical researchers outside the mainstream academy have been collecting increasing documentation. Yet these disparate and uncoordinated efforts have still left a haunting vacuum where Letitia Landon ought to be.

The process of uncovering her has proved both troublesome and troubling. Unlike some marginal figures, she was so famous in her lifetime that she is surrounded by a vast wealth of material, including numerous memoirs published by her contemporaries in the aftermath of her death. Such seemingly trustworthy sources, however, frequently turn out to be a tissue of equivocation, half-truths and downright deceit. Even her own letters can on occasion be shown to tell lies. Often the only way to establish the forensic facts of her life is by recourse to public documents, such as censuses, parish records and wills, though those, too, sometimes contain demonstrable falsehoods.

Most challenging is the problem of interpreting her literary voice, whose unnerving qualities were, as this book will show, the direct result of the fact that it was impossible for her to speak openly. Obsessively circling around her absent I, her poetry gives away both more and less than it promises. To those who met her in the flesh she was a shape-shifter, who did in truth resemble the disputed colour of the chameleon, Even her friends did not know whether to refer to her as Miss Landon or by her nom de plume L.E.L., using both interchangeably.

What to call Landon, or L.E.L.whateer thy name, as one contemporary satirist put it, remains a problem. In this book, I have tried to use L.E.L. when referring to her works and Letitia when telling the story of her life. If I do not always stick to that rule, it is because she made the boundary between her different selves so tantalizingly ambiguous.

Prologue

Between eight and nine oclock on the morning of Monday, October 15, 1838, the body of a thirty-six-year-old Englishwoman, wearing a lightweight dressing gown, was found on the floor of a room in Cape Coast Castle, West Africa. She was the new wife of the British governor, George Maclean, and had arrived there from England only eight weeks previously.

Cape Coast Castle was the largest trading fort on the western coast of Africa: a stark white complex bristling with cannon, perched on the edge of the Atlantic Ocean in what is now Ghana. During the eighteenth century, it had been the grand emporium of the British slave trade. Countless captives had been held in its underground dungeons before being shipped to the Americas, while slave dealers did business in its precincts. Following the Abolition Act of 1807, the castle had remained under British command, its dungeons repurposed for housing local prisoners.

A soldier in a sentry box stood at the entrance to the governors quarters, which were decorated in the European style: prints on the walls, a shining mahogany dining table, impressive table silver. The room in which the body was found, painted a deep blue, featured a toilet table and the deceaseds own portable desk, one of those small wooden boxes, typical of the period, that opened to form a sloping writing surface.

Deaths from disease among Europeans in what was then known as the white mans grave were not uncommon. Indeed, the fatality rate was so great that the local Methodist missionary was having difficulty recruiting volunteers. But this death was different. In the womans hand was a small empty bottle. Her eyes were open and abnormally dilated.

The last person to see the governors wife alive was her maid, Emily Bailey, who had travelled out with her from England. She later testified that she had found Mrs Maclean well when she went in to see her earlier that morning. On her return half an hour later, however, Emily Bailey had had difficulty opening the door. It had been blocked by her mistresss body.

Soon after Mrs Bailey raised the alarm, the castle surgeon arrived. He attempted to revive the patient, but in vain. Garbled news soon spread to the nearby hills. Brodie Cruickshank, a young Scottish merchants agent, arrived at the fort within the hour, mistakenly supposing that it was the governor himself who had perished. In his memoir Eighteen Years on the Gold Coast of Africa, he later recalled his shock on entering the room where Mrs Macleans body had been laid out on a bed. He had dined with the Macleans only the evening before, when she had appeared to be in perfect health. The governor himself was in the room. He had slid down into a chair and was silently staring into space, his face crushed.

Later that very day, an inquest was held at the castle, the jury hastily convened from among the local merchant community. No autopsy was performed, but the empty bottle was produced in evidence and its label carefully transcribed: Acid Hydrocianicum Delatum, Pharm. Lond. 1836, Medium Dose Five Minims, being about one-third the strength of that in former use, prepared by Scheeles proof. The deceased was said to have been in the habit of using the contents, prussic acid in everyday parlance, for medicinal reasons, and to have taken too much by mistake. A verdict of accidental death was recorded.

After the inquest, the corpse was hastily interred under the parade ground. During the burial, a tropical shower burst from the sky in such torrents that a tarpaulin had to be erected over the gravediggers. By the time the final paving stone was replaced it had grown dark. The workmen finished the job by torchlight.

Next page