A LSO BY L UCASTA M ILLER

The Bront Myth

THIS IS A BORZOI BOOK

PUBLISHED BY ALFRED A. KNOPF

Copyright 2019 by Lucasta Miller

All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Alfred A. Knopf, a division of Penguin Random House LLC, New York, and distributed in Canada by Random House of Canada, a division of Penguin Random House Canada Limited, Toronto.

www.aaknopf.com

Knopf, Borzoi Books, and the colophon are registered trademarks of Penguin Random House LLC.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Miller, Lucasta, author.

Title: L.E.L. : the lost life and scandalous death of Letitia Elizabeth

Landon, the celebrated female Byron / Lucasta Miller.

Description: First edition. | New York : Alfred A. Knopf, 2019. | Includes

bibliographical references.

Identifiers: LCCN 2018029621 (print) | LCCN 2018042545 (ebook) | ISBN

9780525655350 (ebook) | ISBN 9780375412783 (hardcover)

Subjects: LCSH : L . E . L . (Letitia Elizabeth Landon), 18021838. | Poets,

English19th centuryBiography.

Classification: LCC PR 4865. L 5 (ebook) | LCC PR 4865. L 5 Z 875 2019 (print) | DDC

821/.7 [ B ]dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018029621

Ebook ISBN9780525655350

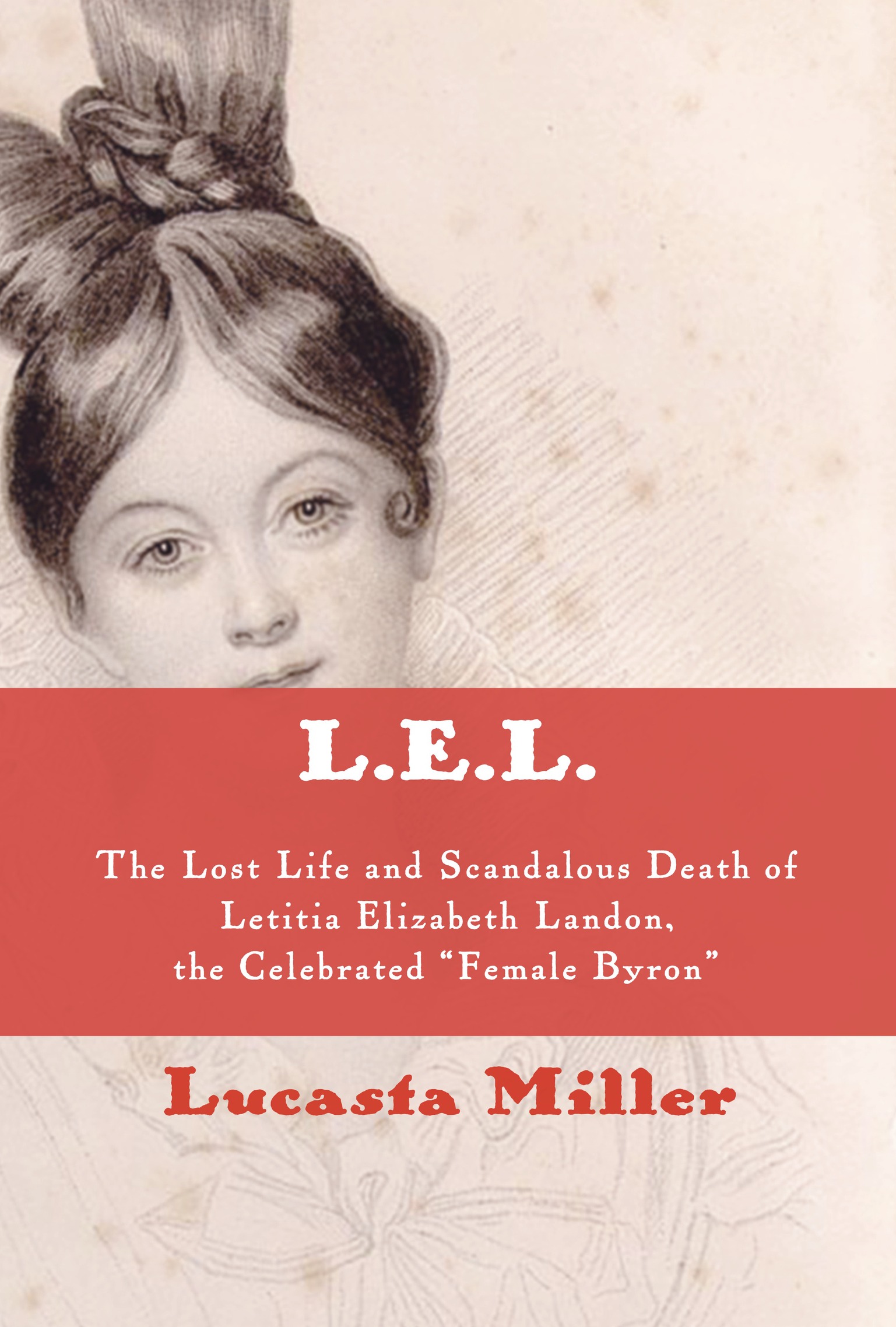

Cover image: Portrait of L.E.L., after D. Maclise, engraved by J. Thompson. Fisher, Son & Co.

Cover design by Carol Devine Carson

v5.4

ep

For I, O, and O

Forget heroin. Just try giving up irony, the deep-down need to mean two things at once, to be in two places at once, not to be there for the catastrophe of a fixed meaning.

E DWARD S T A UBYN

Contents

Preface

This book is about a poet who disappeared: about a woman who pursued her career in a blaze of publicity while leading a secret life that eventually destroyed her, and who left a such a legacy of lies and evasion that her true story can only now be told.

Letitia Elizabeth Landon, who published under her initials, L.E.L., was feted as the female Byron during the 1820s. But after she was found dead in 1838, in West Africa of all places and in suspicious circumstances, the early Victorian publishing industry closed ranks to erase what they had come to see as her shameful history. Her literary reputation declined. She was left on the margins, surrounded by an aura of mystery and occlusion, her work routinely misunderstood.

Over the past couple of decades, she has finally begun to attract more interest. Her work has begun to appear in anthologies of nineteenth-century verse and to be analyzed in scholarly articles. She has even begun to feature in a minor way on many university English literature syllabuses. At the same time, biographical researchers outside the mainstream academy have been collecting increasing documentation. Yet these disparate and uncoordinated efforts have still left a haunting vacuum where Letitia Landon ought to be.

The process of uncovering her has proved both troublesome and troubling. Unlike some marginal figures, she was so famous in her lifetime that she is surrounded by a vast wealth of material, including numerous memoirs published by her contemporaries in the aftermath of her death. Such seemingly trustworthy sources, however, frequently turn out to be a tissue of equivocation, half-truths, and downright deceit. Even her own letters can on occasion be shown to tell lies. Often the only way to establish the forensic facts of her life is by recourse to public documents, such as censuses, parish records, and wills, though those, too, sometimes contain demonstrable falsehoods.

Most challenging is the problem of interpreting her literary voice, whose unnerving qualities were, as this book will show, the direct result of the fact that it was impossible for her to speak openly. Obsessively circling around her absent I, her poetry gives away both more and less than it promises. To those who met her in the flesh she was a shape-shifter, who did in truth resemble the disputed colour of the chameleon, changing its hues with the changeful lights around. Critics lent her others names as if she had no identity of her own: she was the new Corinne or the English improvisatrice, the female Byron, or the Sappho of a polished age. Even her friends did not know whether to refer to her as Miss Landon or by her nom de plume L.E.L., using both interchangeably.

What to call Landon, or L.E.L. whateer thy name, as one contemporary satirist put it, remains a problem. In this book, I have tried to use L.E.L. when referring to her works and Letitia when telling the story of her life. If I do not always stick to that rule, it is because she made the boundary between her different selves so tantalizingly ambiguous.

Prologue

Between eight and nine oclock on the morning of Monday, October 15, 1838, the body of a thirty-six-year-old Englishwoman, wearing a lightweight dressing gown, was found on the floor of a room in Cape Coast Castle, West Africa. She was the new wife of the British governor, George Maclean, and had arrived there from England only eight weeks previously.

Cape Coast Castle was the largest trading fort on the western coast of Africa: a stark white complex bristling with cannon, perched on the edge of the Atlantic Ocean in what is now Ghana. During the eighteenth century, it had been the grand emporium of the British slave trade. Countless captives had been held in its underground dungeons before being shipped to the Americas, while slave dealers did business in its precincts. Following the Abolition Act of 1807, the castle had remained under British command, its dungeons repurposed for housing local prisoners.

A soldier in a sentry box stood at the entrance to the governors quarters, which were decorated in the European style: prints on the walls, a shining mahogany dining table, impressive table silver. The room in which the body was found, painted a deep blue, featured a toilet table and the deceaseds own portable desk, one of those small wooden boxes, typical of the period, that opened to form a sloping writing surface.

Deaths from disease among Europeans in what was then known as the white mans grave were not uncommon. Indeed, the fatality rate was so great that the local Methodist missionary was having difficulty recruiting volunteers. But this death was different. In the womans hand was a small empty bottle. Her eyes were open and abnormally dilated.

The last person to see the governors wife alive was her maid, Emily Bailey, who had traveled out with her from England. She later testified that she had found Mrs. Maclean well when she went in to see her earlier that morning. On her return half an hour later, however, Emily Bailey had had difficulty opening the door. It had been blocked by her mistresss body.

Soon after Mrs. Bailey raised the alarm, the castle surgeon arrived. He attempted to revive the patient, but in vain. Garbled news soon spread to the nearby hills. Brodie Cruickshank, a young Scottish merchants agent, arrived at the fort within the hour, mistakenly supposing that it was the governor himself who had perished. In his memoir