Published in 2018 by Cavendish Square Publishing, LLC

243 5th Avenue, Suite 136, New York, NY 10016

Copyright 2018 by Cavendish Square Publishing, LLC First Edition

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwisewithout the prior permission of the copyright owner. Request for permission should be addressed to Permissions, Cavendish Square Publishing, 243 5th Avenue,

Suite 136, New York, NY 10016. Tel (877) 980-4450; fax (877) 980-4454.

Website: cavendishsq.com

This publication represents the opinions and views of the author based on his or her personal experience, knowledge, and research. The information in this book serves as a general guide only. The author and publisher have used their best efforts in preparing this book and disclaim liability rising directly or indirectly from the use and application of this book.

All websites were available and accurate when this book was sent to press.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Hurt, Avery Elizabeth.

Title: Ada Lovelace: computer programmer and mathematician / Avery Elizabeth Hurt.

Description: New York : Cavendish Square Publishing, [2018] |

Series: History makers | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2017016785 (print) | LCCN 2017019168 (ebook) |

ISBN 9781502633248 (E-book) | ISBN 9781502632951 (library bound)

Subjects: LCSH: Lovelace, Ada King, Countess of, 1815-1852--Juvenile literature. | Women mathematicians--Great Britain--Biography--Juvenile literature. | Women computer programmers--Great Britain--Biography--Juvenile literature. | Mathematicians--Great Britain--Biography--Juvenile literature. | Computer programmers--Great Britain--Biography--Juvenile literature.

Classification: LCC QA29.L72 (ebook) | LCC QA29.L72 H87 2018 (print) |

DDC 510.92 [B] --dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017016785

Editorial Director: David McNamara Editor: Kristen Susienka Copy Editor: Rebecca Rohan Associate Art Director: Amy Greenan Designer: Jessica Nevins Production Coordinator: Karol Szymczuk Photo Research: J8 Media

The photographs in this book are used by permission and through the courtesy of: Cover, p. 126 ART Collection/Alamy Stock Photo; p. 4, 74 Universal History Archive/Getty Images; p. 6 Chronicle/Alamy Stock Photo; p. 9, 14-15 SOTK2011/ Alamy Stock Photo; p. 11 Culture Club/Getty Images; p. 13 Raphael GAILLARDE/Gamma-Rapho via Getty Images; p. 17 g-stockstudio/Shutterstock.com; p. 18 Chronicle/Alamy Stock Photo; p. 23 I.H. Jones/Wikimedia Commons/File:Lord Byron - Childe Harolds Pilgimage - Dugdale edition.jpg/Public Domain; p. 32 National Galleries of Scotland/Getty Images; p. 34 Christophel Fine Art/UIG via Getty Images; p. 40, 65, 67, 85 SSPLTGetty Images; p. 43, 59 Bettmann/Getty Images; p. 48 Robyn Mackenzie/Shutterstock.com; p. 52 Look and Learn / Illustrated Papers Collection/Bridgeman Images; p. 62 Alinari Archives/The Image Works; p. 72 Ada Lovelace/Wikimedia Commons/File:Diagram for the computation of Bernoulli numbers.jpg/Public Domain; p. 77 HultonArchive/Illustrated London News/Getty Images; p. 78 Guildhall Library & Art Gallery/Heritage Images/Getty Images; p. 82-83 Thomas Hosmer/Bridgeman Images; p. 88 Photo12/UIG via Getty Images; p. 94 Topham/The Image Works; p. 100 Park Dale/Alamy Stock Photo; p. 103 Henry Phillips/Wikimedia Commons/File:Ada Lovelace in 1852.jpg/Public Domain; p. 107 Hulton Archive/Getty Images; p. 111 The Illustrated London News/Wikimedia Commons/File:Charles Babbage 1860.jpg/Public Domain; p. 112 CNP Collection/Alamy Stock Photo; p. 114 Nadya Lukic/Shutterstock.com; p. 117 DeAgostini/Getty Images; p. 121 Fine Art Images/Heritage Images/ Getty Images; p. 128 Library of Congress/Getty Images.

A wife and mother with no formal university education wrote the first computer program more than one hundred years before anyone built a computer that could run it. She signed her work with only her initials so as not to draw attention to the fact that she was a woman. No one much noticed anyway. For one hundred years after her death, she was more or less forgotten. The world, it seemed, was not ready for what Ada Lovelace had to say.

Opposite: Many think Ada Lovelace wrote the worlds first computer program.

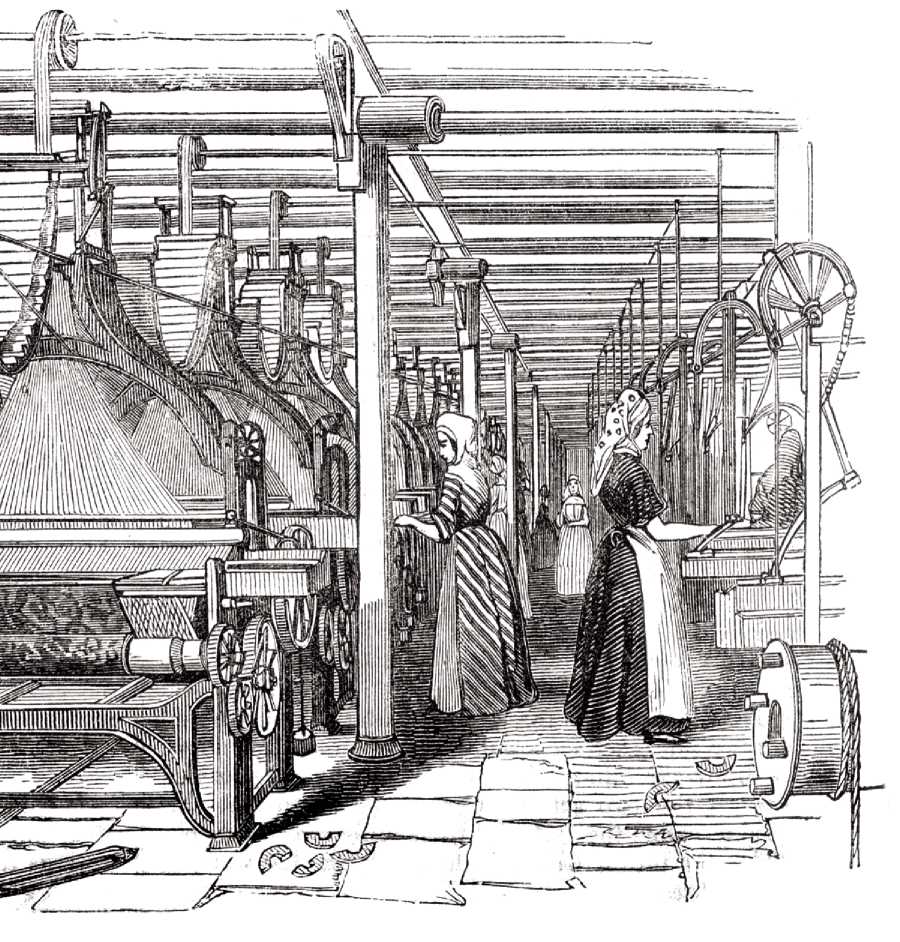

Englands Industrial Revolution was a time of great change and excitement.

Ada Lovelace (or more officially, Augusta Ada Byron) was born in December 1815, in London, England, in the midst of two important historical epochs : the Industrial Revolution and the Romantic period in art and literature.

The Industrial Revolution, which in England lasted roughly from 1780 to 1850, was a time of almost dizzying technological and social change. Jobs that had previously been undertaken by human or animal power were now being carried out much more efficiently by a variety of new machines powered by steam or electricity. Steam-powered trains crisscrossed the country; factories employed workers to produce cotton on spinning jennies and fabric on power looms; and people sent messages across the country rapidly by telegraph. The industrial age was both powered by and the inspiration for scientific change. Scientists were charting the stars, exploring the secrets of magnetism and electricity, and discovering the history of the planet by the study of geology. The period was described by Richard Holmes in The Age of Wonder as a time driven by a common ideal of intense, even reckless, personal commitment to discovery. But as Holmes also points out in his book's subtitle, How the Romantic Generation Discovered the Beauty and Terror of Science, the change was not welcomed by everyone.

Like most change, the industrial age was both thrilling and scary, and some people greatly resisted itor at least certain aspects of it. Romanticism was in many ways a reaction to the rationalism and materialism that made the technological accomplishments of the period possible. Romanticism valued the imagination, the individual, and spontaneity. It revered nature and preferred the emotions to reason, the senses to intellect, the creative spirit to a strict adherence to rules and systems. The factories of the Industrial Revolution were offensive to the spirit of Romanticism. The rigid procedures of the scientific method were off-putting to the Romantic ideal.

Not everyone appreciated the changes brought by the Industrial Revolution. Loom operators were especially troubled.