Published in 2020 by Cavendish Square Publishing, LLC

243 5th Avenue, Suite 136, New York, NY 10016

Copyright 2020 by Cavendish Square Publishing, LLC

First Edition

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any meanselectronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwisewithout the prior permission of the copyright owner. Request for permission should be addressed to Permissions, Cavendish Square Publishing, 243 5th Avenue, Suite 136, New York, NY 10016. Tel (877) 980-4450; fax (877) 980-4454.

Website: cavendishsq.com

This publication represents the opinions and views of the author based on his or her personal experience, knowledge, and research. The information in this book serves as a general guide only. The author and publisher have used their best efforts in preparing this book and disclaim liability rising directly or indirectly from the use and application of this book.

All websites were available and accurate when this book was sent to press.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Hurt, Avery Elizabeth, author.

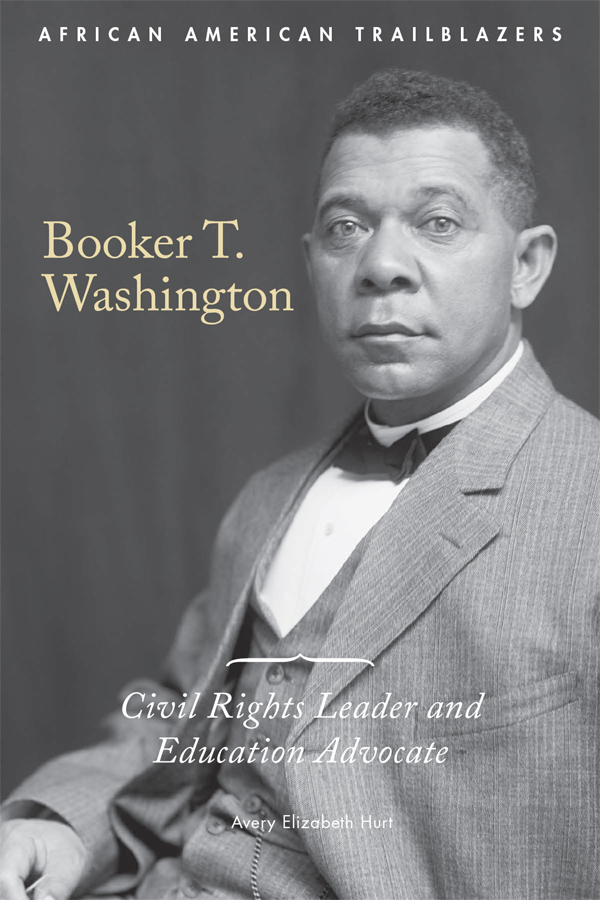

Title: Booker T. Washington : civil rights leader and education advocate / Avery Elizabeth Hurt.

Description: First edition. | New York : Cavendish Square, [2020] |

Series: African American trailblazers | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2018047437 (print) | LCCN 2018051209 (ebook) | ISBN 9781502645593 (ebook) | ISBN 9781502645586 (library bound) | ISBN 9781502645579 (pbk.)

Subjects: LCSH: Washington, Booker T., 1856-1915--Juvenile literature. |

African Americans--Biography--Juvenile literature. | Educators--United States--Biography--Juvenile literature. | Tuskegee Institute--Juvenile literature.

Classification: LCC E185.97.W4 (ebook) | LCC E185.97.W4 H87 2020 (print) | DDC 370.92 [B] --dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018047437

Editorial Director: David McNamara

Editor: Kristen Susienka

Copy Editor: Alex Tessman

Associate Art Director: Alan Sliwinski

Designer: Joe Parenteau

Production Coordinator: Karol Szymczuk

Photo Research: J8 Media

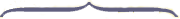

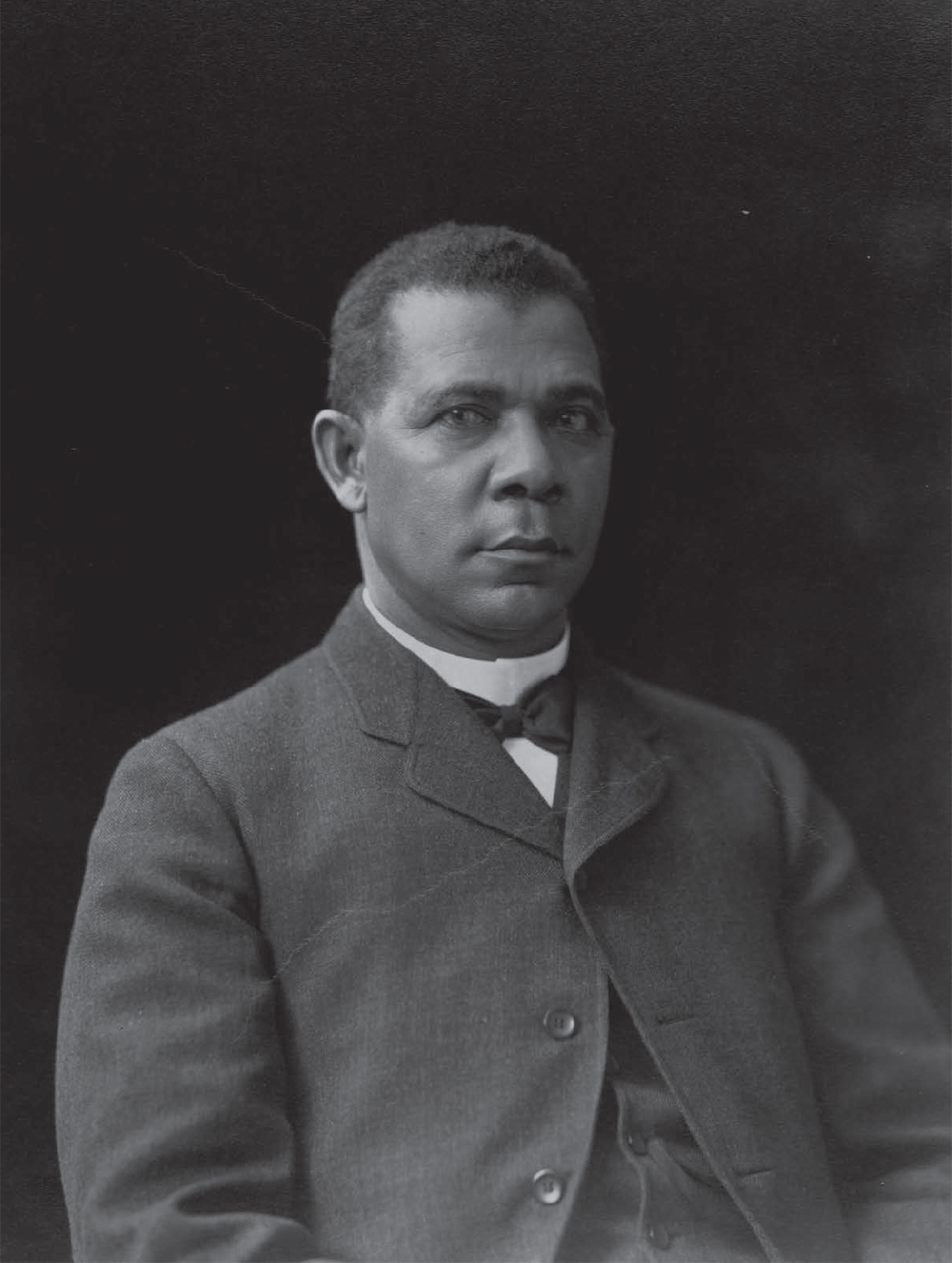

The photographs in this book are used by permission and through the courtesy of: Cover, Frances Benjamin Johnston, (1866-1952) Library of Congress/File: Booker T. Washington, c. 1895.jpg/Wikimedia Commons/Public Domain; p. Peck (Akron, Ohio) Library of Congress/File: Booker T. Washington cph.3b04335.jpg/Wikimedia Commons/Public Domain.

Printed in the United States of America

CONTENTS

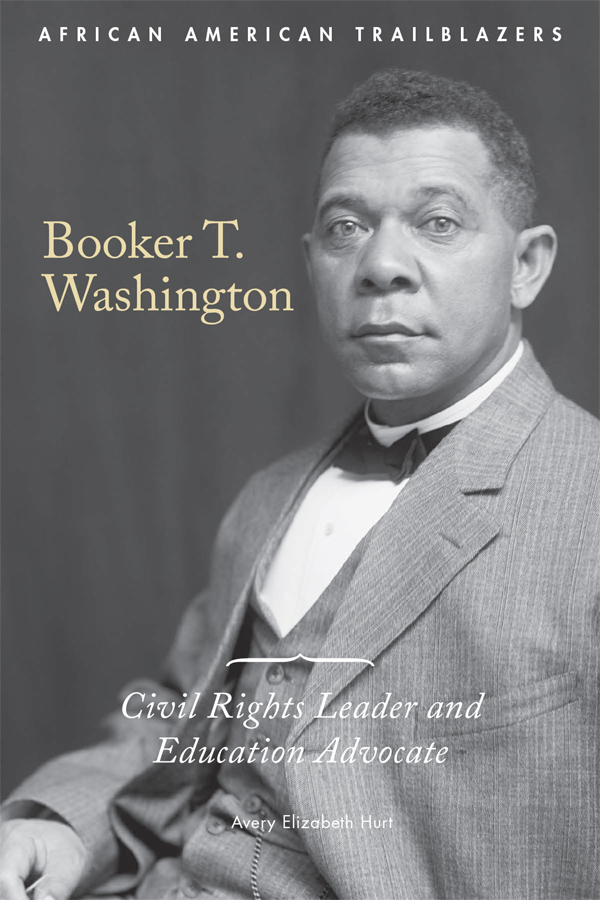

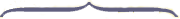

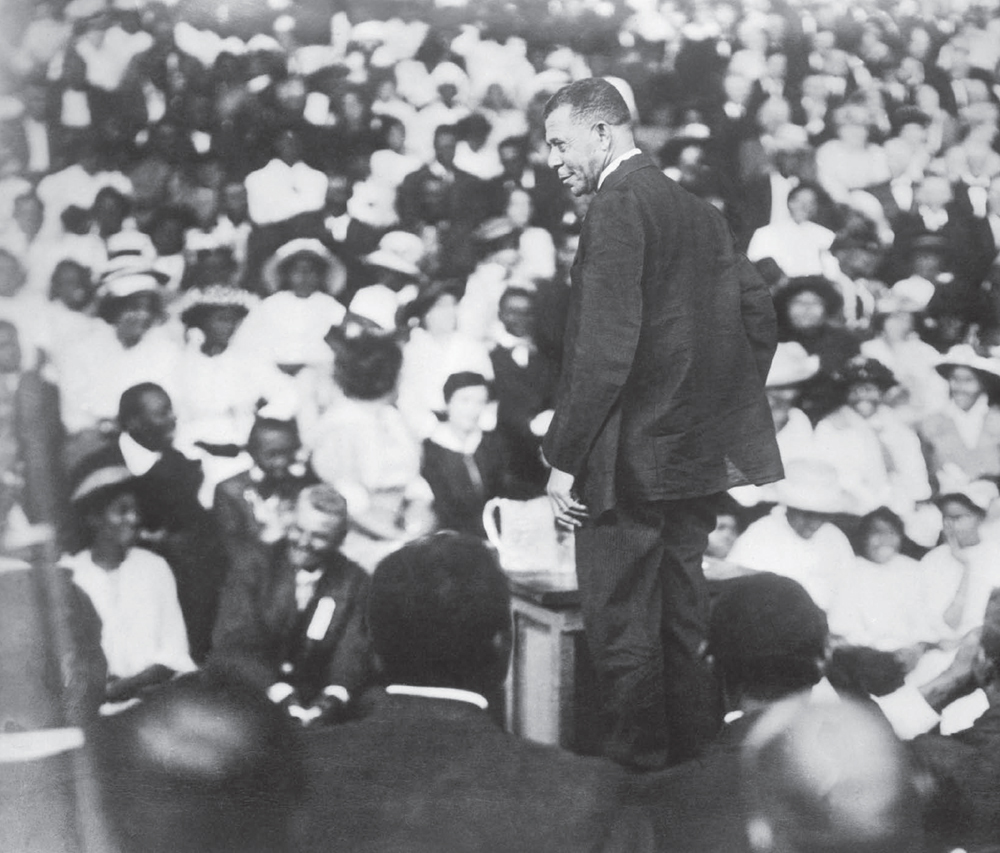

Booker T. Washington was a striking man with a distinguished character. For much of his adulthood he advocated for education for all African Americans.

INTRODUCTION

From Cabin

to Campus

T oday we know him as Booker T. Washington, but when he was a child, he was known only as Booker. He was born a slave in 1856, slightly before the start of the Civil War. Only after he and his people were freed a little more than a decade later would he choose for himself a last name and discover that his mother had given him a middle name (Taliaferro) when he was born.

Longing for Education

Young Booker wasnt bothered much by the fact that he had no last name, but he was much troubled by not being allowed to learn. Slaves were not allowed to attend school or even learn to read, and Washington longed for education.

When the war was over and the slaves were set free, Washington finally had a chance at education, though it wasnt easy. He made great sacrifices in order to learn. He stayed up late at night after work studying, and he walked long distances to meet with teachers. Eventually, he graduated from college and immediately began teaching others. He would found one of the nations most successful historically black colleges, what is now Tuskegee University. He would become one of the nations most beloved and respected educators. In his later years, he was the acknowledged leader of the African American community.

Establishing Purpose

Washingtons purpose in life was to help African Americans become successful in the postslavery world. The years just after emancipation were hard, and it would be many more before the majority of whites accepted blacks as equal citizens. After 1865, many whites, especially in the South where most blacks lived, were actively hostile to their recently freed fellow Americans. Laws to protect blacks and give them political rights were ignored, and other laws were passed to restrict their rights and freedoms.

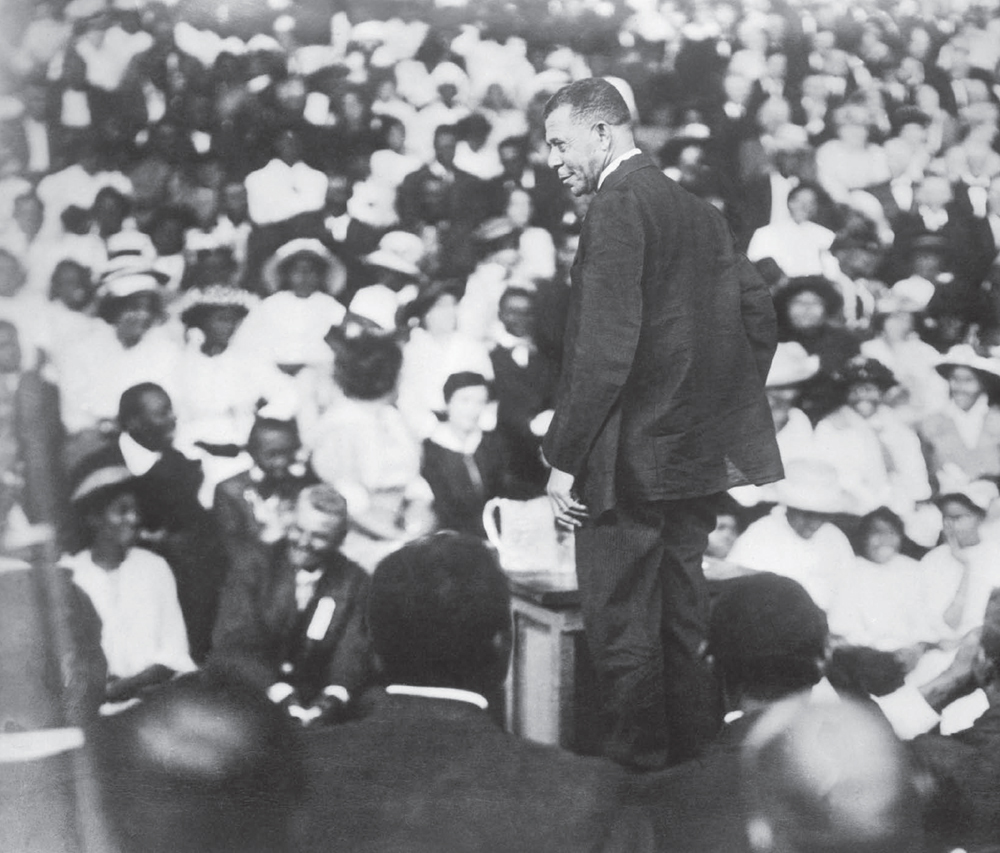

Booker T. Washington (standing) addresses students and administrators at Tuskegee University.

Guiding his people through these difficult years was a challenge for Washington. He believed that economic independence and entrepreneurship were essential if African Americans were to survive. Constitutional amendments made blacks voting citizens and guaranteed them the protection of the law. Still, white people were in charge, and during Washingtons lifetime there was little blacks could do to protect their rights and protect themselves from violence by hostile whites. Washington resisted activities that further antagonized whites and advised his fellow blacks to work hard to get along with whites and not demand political and social equality.

He believed that blacks should concentrate first on education and entrepreneurship. When they owned land and businesses and had proved themselves both capable and necessary to the white economy, only then would they be ready for political action and involvement. His tremendous success at Tuskegee proved the value of his approach, and by far most African Americans agreed with his methods. However, some thought that he was too accepting of injustice and too slow to demand change. In his later years, he was reviled by some younger black leaders, such as W. E. B. Du Bois. He was accused of being a sell-out and of holding back his race. Nevertheless, his work in education and his tireless efforts to give African Americans a sense of dignity and self-worth helped create a black middle class and make possible the generation that launched and led the civil rights movement of the 1950s and 1960s, decades after Washingtons death.

Today many people still wonder if Washington did more good than harm. Might civil rights for blacks have come earlier if he had been less accommodating of white power? Or did his slow and measured approach prepare and protect his people until the time was right for the movement? Historians do not agree, but there is no denying Booker T. Washington helped many African Americans out of poverty and that he is an inspiration to people, both black and white, even today.

The Emancipation Proclamation was signed by President Abraham Lincoln on January 1, 1863.

CHAPTER ONE