To my adopted home, Birmingham, Alabama, where people marched in the streets, sat at lunch counters, and stood firm in their resolvea place where people are still working to right wrongs and make the world a better place. I am both proud and humbled to call you home.

Published in 2020 by The Rosen Publishing Group, Inc. 29 East 21st Street, New York, NY 10010

Copyright 2020 by The Rosen Publishing Group, Inc.

First Edition

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Hurt, Avery Elizabeth, author.

Title: The fight for civil rights / Avery Elizabeth Hurt.

Description: New York : Rosen YA, 2020 | Series: Activism in action: a history | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2018010899| ISBN 9781508185413 (library bound) | ISBN 9781508185406 (pbk.)

Subjects: LCSH: African AmericansCivil rightsHistory 20th centuryJuvenile literature. | Civil rights movementsUnited StatesHistory20th centuryJuvenile literature. | United StatesRace relationsJuvenile literature.

Classification: LCC E185.61 .H977 2020 | DDC 323.1196/0730904dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018010899

Manufactured in the United States of America

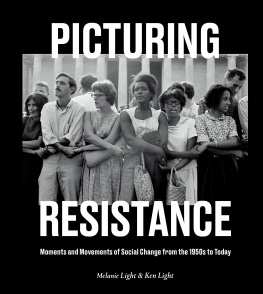

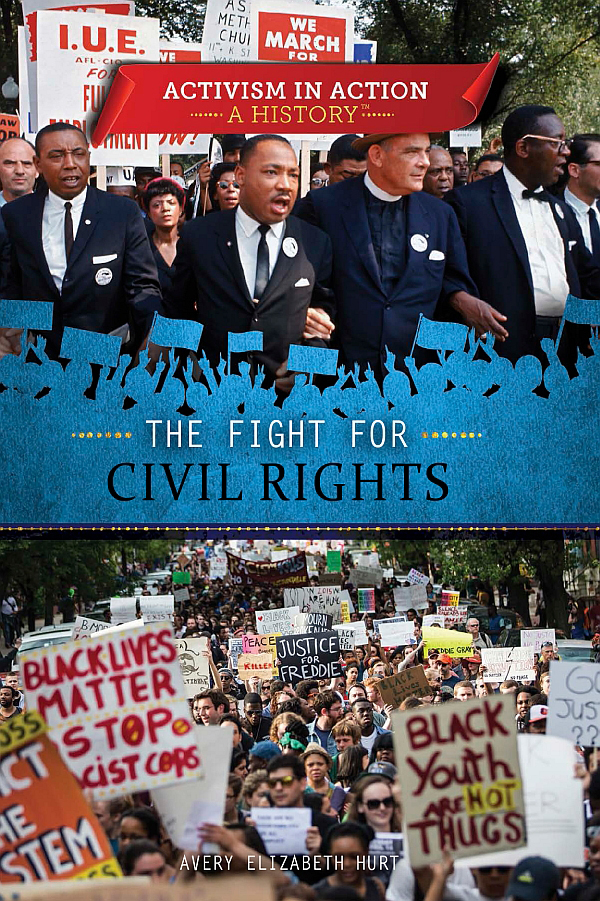

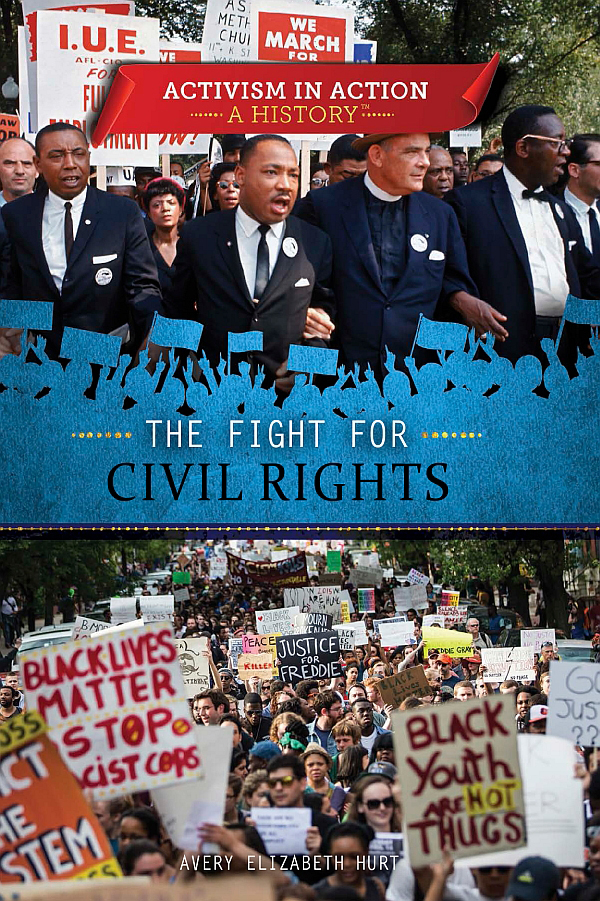

On the cover: Courageous leaders, such as Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. (top), and nationwide movements, such as Black Lives Matter, help to inspire change in the fight for civil rights.

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

I n 1861, the United States was torn in two over the issue of slavery. The Union of the North wanted to end slavery, while the Confederacy of the South wanted the practice to continue. The nation endured a four-year civil war, and in 1865, slavery was abolished. In the years that followed, former slaves and their descendants were guaranteed full citizenship. Black men were even given the right to vote. Things looked promising, until the nation systematically began denying them their civil rights. A system of racial discrimination in the South, and less systematic but no less damaging discrimination in the North, kept blacks from enjoying the rights, privileges, and opportunities that white citizens took for granted.

African Americans were not only denied their civil rights but were often terrorized. If a black person dared to challenge or even question the status quo, he or she was likely to be beaten or murdered. It was not uncommon for mobs of angry white men to hang a black person for a minor offense or for no reason at all. A white person who committed a similar crime was rarely punished. As the years went on, blacks began to organize and take steps to change the system. But real and lasting changes were few and far between.

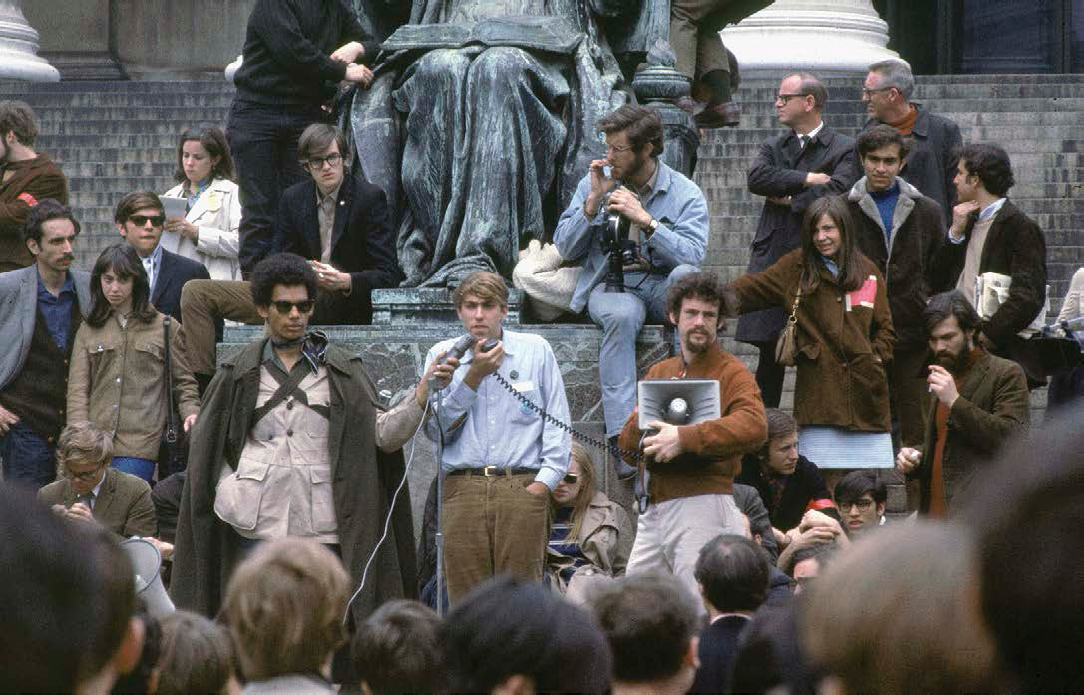

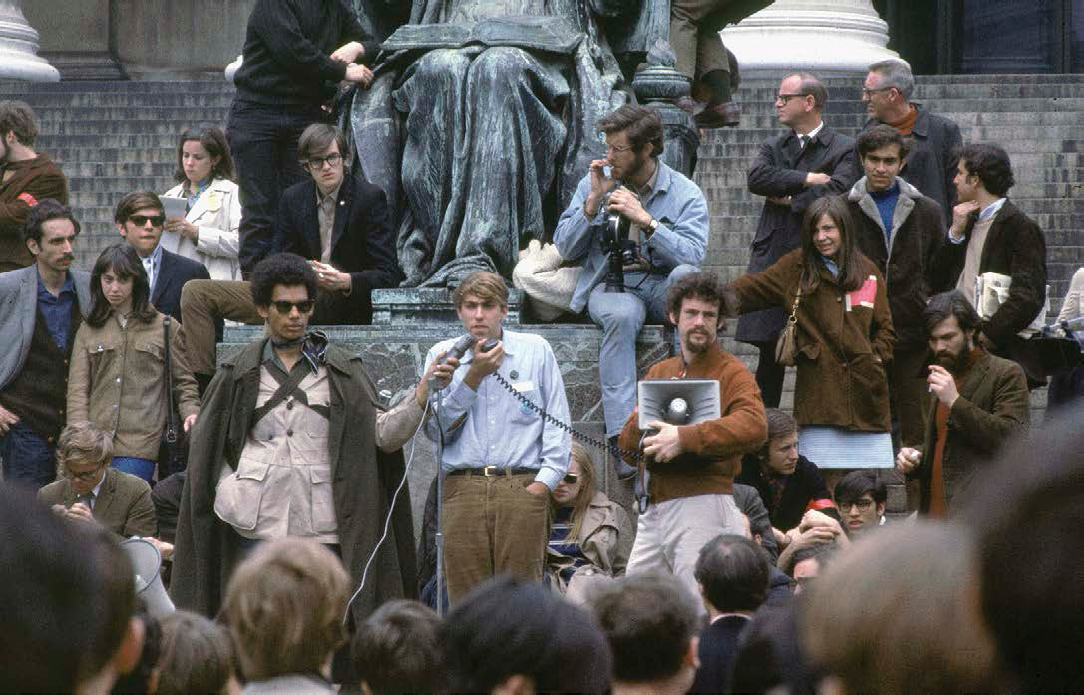

In 1968, Students at Columbia University listen as speakers from the Students for a Democratic Society speak out about civil rights.

In the middle of the twentieth century, things began to change. African Americans had had enough. Leaders such as Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., Rosa Parks, Bayard Rustin, Gloria Richardson, Ralph Abernathy, Fred Shuttlesworth, John Lewis, A. Philip Randolph, and many more took to the streets to make their voices heard. Hundreds of thousands of people followed them, including schoolchildren and college students, men and women, the young and old.

The civil rights movement was one of the most effective social movements in history. Between the mid-1950s and the mid-1960s, civil rights activists in the United States challenged segregation in schools, public transportation, and public spacesand won. They crashed through barriers for voting rights and forced the government to pass laws to provide equal job opportunities and end discrimination in the workplace. In a manner of speaking, they held up a mirror for the nation to look at its own hatred.

Activists achieved great strides in the civil rights movement by using nonviolent techniques of passive resistance. They didnt throw bombs, though bombs were thrown at them. They didnt burn down buildings, though many of their homes and churches were burned. They marched. They sang. They refused to leave when told to do so, and they refused to leave when sprayed with fire hoses. Activists marched in small towns and in big cities. They even marched up to the nations capital. Every step, action, song, and refusal to give in changed a nation and its place in the world. The exciting and sometimes heartbreaking stories of these change makers portray them as full of courage, pride, and loveand ultimately triumphant, propelling the fight for civil rights.

CHAPTER ONE

THE LONG MARCH AHEAD

O n March 7, 1965, six hundred demonstrators gathered on a chilly Sunday in Selma, Alabama. They planned to march to the states capital, Montgomery, almost 50 miles (80 kilometers) away. Their goal was to highlight the need for laws that would protect the voting rights of African Americans. They also marched to commemorate the death of Jimmy Lee Jackson, who had been fatally shot by a state trooper a few weeks earlier. Jackson had been trying to protect his mother at a voter registration protest in Marion, Alabama.

Marchers set out on US Route 80, heading east toward Montgomery. The participating men, women, and children were hopeful, unarmed, and walking peacefully. Some were holding hands. Others were singing softly or talking quietly with fellow marchers. After six blocks, they reached the Edmund Pettus Bridge, which stretches across the Alabama River. On the other side of the bridge were state and local law enforcement officers, waiting for the peaceful demonstrators. Most of the officers were on foot. Some were on horseback. The activists paused for a moment and then began crossing the bridge. One of the march leaders, twenty-four-yearold John Lewis, suggested they pray. Word spread throughout the crowd, and prayers were said as they crossed the bridge. The police, however, attacked the peaceful demonstrators with clubs and tear gas. They rode their horses into the crowd, beating people with nightsticks and spraying them with tear gas. The police forced the marchers back across the bridge and back through Selma. Seventeen people, including Lewis, were injured on what became known as Bloody Sunday.

People line the streets of Montgomery, Alabama, to watch the Selma to Montgomery marchers as they walk by in March 1965.

ONCE MORE, WITH FEELING

Two days later, on March 9, fifteen hundred protesters headed out again from Selma toward the Edmund Pettus Bridge. This time, they were led by civil rights leader Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. National news shows had covered the story of Bloody Sunday, and the world was watching. Protesters did not intend to march all the way to Montgomery but planned to walk to the Edmund Pettus Bridge, where Alabama state troopers had set up a barricade to keep them from crossing. Marchers did not confront the police. Instead, they approached the barricades, knelt, and prayed. They then turned around and walked back to Selma. In cities across the country, people held marches to show solidarity with the protesters in Alabama.

Next page