ADAS ALGORITHM: HOW LORD BYRONS DAUGHTER ADA LOVELACE LAUNCHED THE DIGITAL AGE

Copyright 2014 by James Essinger

Originally published by Gibson Square, Ltd, London, 2013

First Melville House printing: October 2014

Melville House Publishing

145 Plymouth Street

Brooklyn, NY 11201

and

8 Blackstock Mews

Islington

London N4 2BT

mhpbooks.com facebook.com/mhpbooks @melvillehouse

Library of Congress

Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Essinger, James, 1957

Adas algorithm : how Lord Byrons daughter Ada Lovelace launched the digital age / James Essinger.

pages cm

Includes bibliographical references.

ISBN 978-1-61219-408-0 (hardback)

ISBN 978-1-61219-409-7 (ebook)

1. Lovelace, Ada King, Countess of, 18151852. 2. Babbage, Charles, 17911871. 3. Women mathematiciansGreat BritainBiography. 4. MathematiciansGreat BritainBiography. 5. ComputersHistory19th century. I. Title.

QA29.L72E87 2014

510.92dc23

[B]

2014021837

Design by Christopher King

v3.1

Advance Praise forAdas Algorithm

[An] absorbing biography Essingers tome is undergirded by academic research, but it is the authors prose, both graceful and confident, that will draw in a general readership. Readers are treated to an intimate portrait of Lovelaces short but significant life.

Publishers Weekly

Praise for the British Edition

[Adas Algorithm] will have us forever wondering what might have been.

The Independent

Entertaining and illuminating.

The Times Literary Supplement

Essinger displays not only verve and affection but also great scholarship.

Times Educational Supplement

Praise for Jacquards Web

Essinger tells his story with passion and with a gracious willingness to help the lay reader grasp the intricacies of technology.

The Wall Street Journal

With wit and imagination, Essinger has woven a marvelous tapestry.

Entertainment Weekly

Fascinating.

The Economist

Essinger does more than weave together science, history, and business: he sheds light on the nature of innovation His book deftly shows how even the most surprising breakthroughs are based on the work of others, and need a host of enabling factors to take root His tale of cultural, economic, and personal factors that enable ideas to become real tools makes this book a welcome addition to the literature of innovation.

The Boston Globe

An important and highly readable addition to an essential history.

CERN Courier

Essinger travels down some fascinating byways in the history of technology A compelling narrative that links past and present in surprising and illuminating ways.

Waterstones Books Quarterly

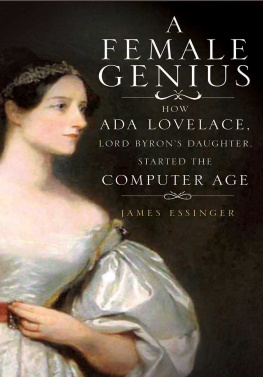

ALSO BY JAMES ESSINGER

Spellbound: The Surprising Origins and Astonishing Secrets of English Spelling

Jacquards Web: How a Hand-Loom Led to the Birth of the Information Age

This book is dedicated

in friendship and admiration

to

Dr Doron Swade MBE

and

Dr Betty Alexandra Toole

Contents

Preface

Maybe youre fascinated by Ada Lovelace already. If not, I hope by the end of Adas Algorithm you will be.

I became intrigued by Ada myself and soon enthralled by her while writing my book Jacquards Web: How a Hand-Loom Led to the Birth of the Information Age (2004), by which time a general interest in Adas work was well established. There is a popular software language called Ada, which was originally developed by the U.S. Department of Defense in the late 1970s to unite a host of different programming languages. In 2009, an international Ada Lovelace Day was launched on Londons Southbank to celebrate the achievement of women in science, technology, engineering and mathematics. There is a Hollywood movie about Ada (written by Shanee Edwards), Enchantress of Numbers, in development.

It would, at least at first glance, appear that science has a chequered record of treating women as equals of men. Indeed, female staff at Bletchley Park, the wartime decryption headquarters that cracked German ciphers, were largely unrecognised for their painstaking work. Meanwhile Rosalind Franklin, who did much of the Nobel Prizewinning work on DNA, was ignored in all official recognition of the deduction of the existence of the double helix, to the embarrassment of the male scientists involved.

Whether this is historically a case of sexism or social conditioning of both genders is beyond the scope of this book. (Change is afoot for the future as Elinor Ostrom quipped on becoming in 2009 the first female Nobel Prize winner for economics, I wont be the last.) What is clear, though, is that there is a surging interest in the history of women who have contributed to and been involved with science.

While Lord Byron, Adas father, cast a long shadow over her life, she was just over a month old when they parted company forever and so she never met him in any meaningful sense. A much more durable person in her life was Lady Byron, who had been well educated by her enlightened parents and brought up to move in liberal circles. Lady Byron maintained a ferocious control over her daughters life and, as it would turn out, death.

Ada Lovelaces story is most closely interwoven with that of her close friend Charles Babbage, the scientist who invented the first mechanical computer. Like Babbage, Ada was tireless in the pursuit of knowledge. On Monday, August 14, Ada wrote to him:

I wish to add my mite towards expounding & interpreting the Almighty, & his laws & works, for the most effective use of mankind; and certainly, I should feel it no small glory if I were enabled to be one of his most noted prophets (using this word in my own peculiar sense) in this world.

Ada and Babbages letters became so intimate that they clearly suggest that they had what was essentially a romantic friendship.

Unlike Babbage himself, Ada Lovelace saw beyond the immediate purpose of his inventions. He had little interest in such speculations and appears to have seen his inventions as mere calculators. But Ada believed that a whole new area of discovery awaited once real-world and abstract mathematics could be linked through calculations that were beyond the scope of human abilities. She had a vivid, thrilling and disturbingly prescient vision that such a computer, for example, might handle pieces of music of any degree of complexity or extent: a familiar and even everyday truth over a century and a half later but inconceivable to scientists at the time.

Ada was passionate, kind, imaginative, excitable and emphatic. She loved emphasising words in the letters and documents she wrote by underlining them (such words are italicised in this book where she is quoted). She was regularly in poor health and used mathematics as a way to regain her focus. Later in life, when she was in severe pain from cancer, she would use medication we now recognise as mind-altering drugs. After a long and excruciating battle with the disease that she appears to have suffered without complaint, she died of cancer at thirty-six, the same age at which her father Lord Byron passed away.

One of the fiercest criticisms of Ada is found in