DAVID LEAVITT

The Man Who Knew Too Much

Alan Turing and the Invention of the Computer

For Markfriend, comrade, partner

David Foster Wallace

Everything and More: A Compact History of

Sherwin B. Nuland

The Doctors Plague: Germs, Childbed Fever, and the Strange Story of Ignc Semmelweis

Michio Kaku

Einsteins Cosmos: How Albert Einsteins Vision Transformed Our Understanding of Space and Time

Barbara Goldsmith

Obsessive Genius: The Inner World of Marie Curie

Rebecca Goldstein

Incompleteness: The Proof and Paradox of Kurt Gdel

Madison Smartt Bell

Lavoisier in the Year One: The Birth of a New Science in an Age of Revolution

George Johnson

Miss Leavitts Stars: The Untold Story of the Forgotten Woman Who Discovered How to Measure the Universe

David Leavitt

The Man Who Knew Too Much: Alan Turing and the Invention of the Computer

William T. Vollman

Uncentering the Earth: Copernicus and the Revolutions of the Heavenly Spheres

David Quammen

The Reluctant Mr. Darwin: An Intimate Portrait of Charles Darwin and the Making of his Theory of Evolution

FORTHCOMING TITLES

Richard Reeves on Rutherford and the Atom

Daniel Mendelsohn on Archimedes and the Science of the Ancient Greeks

General Editors: Edwin Barber and Jesse Cohen

Contents

I n Alexander Mackendricks 1951 Ealing comedy The Man in the White Suit , Alec Guinness plays Sidney Stratton, a dithery, even childlike chemist who creates a fabric that will never wear out or get dirty. His invention is heralded as a great step forwarduntil the owners of the textile mills at which he was employed, along with the members of the unions representing his fellow workers, realize that it will put them all out of business. Soon enough, these perennial antagonists join forces to trap Stratton and destroy his fabric, which he is wearing in the form of a white suit. They chase him down, corner him, and seem about to murder him, when at the very last moment, the suit begins to disintegrate. Failure thus saves Stratton from the industry he threatens, and saves the industry from obsolescence.

It goes without saying that any parallel drawn between Sidney Stratton and Alan Turingthe English mathematician, inventor of the modern computer, and architect of the machine that broke the German Enigma code during World War IImust by necessity be inexact. For one thing, such a parallel demands that we view Stratton (especially as portrayed by the gay Guinness) as at the very least a protohomosexual figure, while interpreting his hounding as a metaphor for the more generalized persecution of homosexuals in England before the 1967 decriminalization of acts of gross indecency between adult men. This is obviously a reading of The Man in the White Suit that not all of its admirers will accept, and that more than a few will protest. To draw a parallel between Sidney Stratton and Alan Turing would also require us to ignore a crucial difference between the two scientists: while Stratton is hounded because of his discovery, Turing was hounded in spite of it. Far from the failure that is Strattons white suit, Turings machinesboth hypothetical and realnot only initiated the age of the computer but played a crucial role in the Allied victory over Germany in World War II.

Why, then, labor the comparison? Only because, in my view, The Man in the White Suit has so much to tell us about the determining conditions of Alan Turings short life: homosexuality, the scientific imagination, and England in the first half of the twentieth century. Like Stratton, Turing was nave, absent-minded, and oblivious to the forces that threatened him. Like Stratton, he worked alone. Like Stratton, he was interested in welding the theoretical to the practical, approaching mathematics from a perspective that reflected the industrial ethos of the England in which he was raised. And finally, like Stratton, Turing was hounded out of the world by forces that viewed him as a danger, much as the eponymous hero of E. M. Forsters Maurice fears that he will be hounded out of the world if his homosexuality is discovered. Dubbed a security risk because of his heroic work during World War II, Turing was arrested and tried a year after the opening of The Man in the White Suit on charges of committing acts of gross indecency with another man. As an alternative to a prison sentence, he was forced to endure a humiliating course of estrogen injections intended to cure him. Finally, in 1954, he committed suicide by biting into an apple dipped in cyanidean apparent nod to the poisoned apple in one of his favorite films, the Disney version of Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs , and one which writers on Turing in subsequent years have made much of.

In a letter written to his friend Norman Routledge near the end of his life, Turing linked his arrest with his accomplishments in an extraordinary syllogism:

Turing believes machines think

Turing lies with men

Therefore machines cannot think

His fear seems to have been that his homosexuality would be used not just against him but against his ideas. Nor was his choice of the rather antiquated biblical locution to lie with accidental: Turing was fully aware of the degree to which both his homosexuality and his belief in computer intelligence posed a threat to organized religion. After all, his insistence on questioning humankinds exclusive claim to the faculty of thought had brought on him a barrage of criticism in the 1940s, perhaps because his call for fair play to machines encoded a subtle critique of social norms that denied to another populationthat of homosexual men and womenthe right to a legitimate and legal existence. For Turingremarkably, given the era in which he came of ageseems to have taken it as a given that there was nothing at all wrong with being homosexual; more remarkably, this conviction came to inform even some of his most arcane mathematical writings. To some extent his ability to make unexpected connections reflected the startlingly originaland at the same time startlingly literalnature of his imagination. Yet it also owed, at least in part, to his education at Sherborne School, at Kings College during the heyday of E. M. Forster and John Maynard Keynes, and at Princeton during the reign of Einstein; to his participation in Wittgensteins famous course on the foundations of mathematics; and to his secret work for the government at Bletchley Park, where the necessity of contending with an elusive German cipher on a daily basis exercised his ingenuity and compelled him to loosen up his already limber mind.

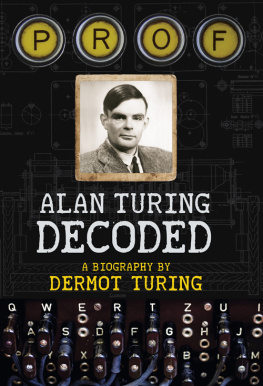

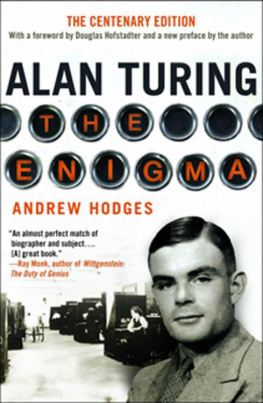

The fallout of his arrest and suicide was that for years his contribution to the development of the modern computer was minimized and in some instances erased altogether, with John von Neumann often being given credit for ideas that really originated with Turing. Indeed, only after the declassification of documents relating to his work at Bletchley Park, and the subsequent publication of Andrew Hodges magisterial 1983 biography, did this great thinker begin to receive his due. Now he is acknowledged as one of the most important scientists of the twentieth century. Even so, most popular accounts of his work either fail to mention his homosexuality altogether or present it as a distasteful and ultimately tragic blot on an otherwise stellar career.

I first heard about Alan Turing in the mid-eighties, when he was often recalled as a sort of martyr to English intolerance. Although I had taken a basic course in calculus in high school, in college and afterward Id made a point of avoiding mathematics. Id made an even greater point of steering clear of computer science, even as I grew, like most Americans, increasingly dependent on computers. Then I started to read more about Turing, and to my own surprise, I found myself becoming as fascinated by the work hed done as by the life hed led. Within the daunting morass of Greek and German letters, logic symbols, and mathematical formulae that enwebbed the pages of his papers, there lay the prose of a speculative and philosophical writer who thought nothing of asking whether a computer could enjoy strawberries and cream, or of resolving a bothersome problem in logic by means of an imaginary machine writing 1s and 0s on an endless tape, or of putting the principles of pure mathematics to the practical goal of breaking a cipher.

Next page