Jon Agar - Turing and the Universal Machine: The Making of the Modern Computer

Here you can read online Jon Agar - Turing and the Universal Machine: The Making of the Modern Computer full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. publisher: Icon Books Ltd, genre: Religion. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

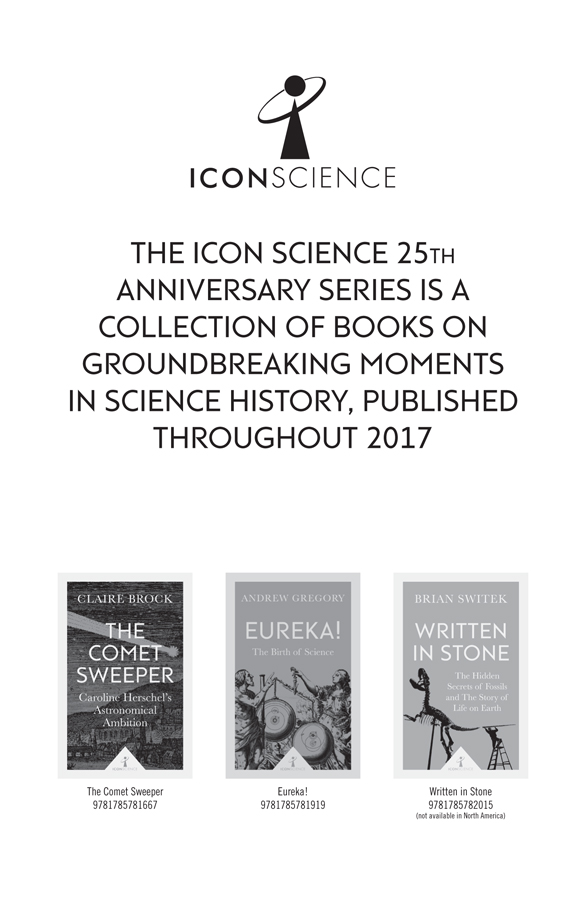

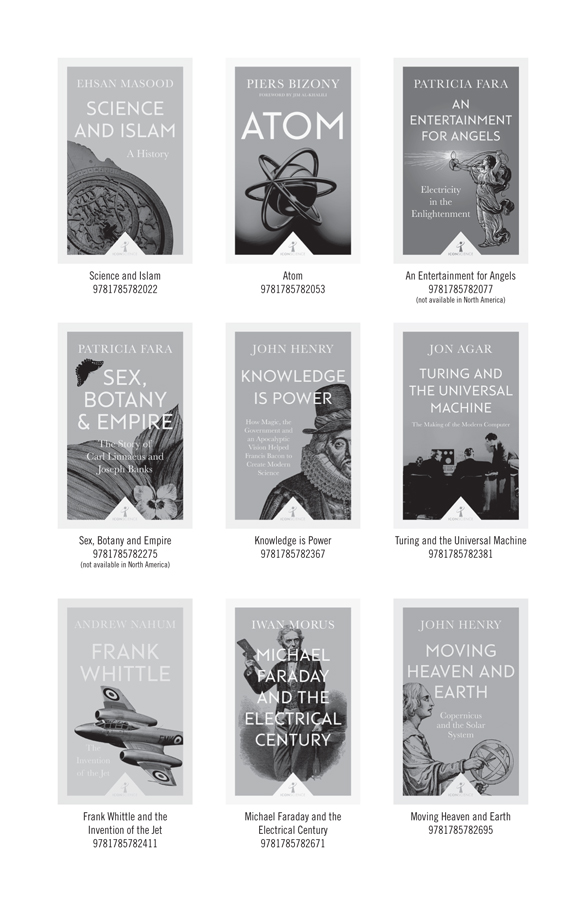

Turing and the Universal Machine: The Making of the Modern Computer: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Turing and the Universal Machine: The Making of the Modern Computer" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Jon Agar: author's other books

Who wrote Turing and the Universal Machine: The Making of the Modern Computer? Find out the surname, the name of the author of the book and a list of all author's works by series.

Turing and the Universal Machine: The Making of the Modern Computer — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Turing and the Universal Machine: The Making of the Modern Computer" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

I would like to thank Jon Turney and Bat for reading my manuscript and suggesting improvements. (Remaining errors, of course, should be blamed on me or on the universal machine that helped me write this book.)

Jon Agar is Professor of Science and Technology Studies at University College London. He is a historian of science and technology and is the author of Science in the Twentieth Century and Beyond (2012), The Government Machine: a Revolutionary History of the Computer (2003), and Constant Touch: a Global History of the Mobile Phone (Icon Books, 2003, updated edition published in 2013).

Take out a Swiss Army knife and have a good look at it. I have one here. It has the full range of gizmos and attachments. There is a pair of scissors, a retractable pen, a ruler, a magnetic Phillips screw-driver, some tweezers, a small blade and an emergency blade. There is even a cuticle pusher and a nail file, essential for any well-manicured soldier. Nothing to get stones out of horses hooves, but very handy nevertheless.

Swiss Army knives are versatile machines: they can be put to many different uses. Other machines are far more restricted. A lawnmower, for example, can mow lawns, but not much else. It has been designed for a specific purpose, and the function of each part of it follows. The handle is there so that it can be pushed by an adult human. The engine will power the blades, which would be exhausting to turn by hand. The blades are set so that grass is cut to an inch off the ground, the height we like lawns to be. While the lawnmower can be put to other purposes propping open a door, perhaps it will usually not be very effective. No one tries to fly the Atlantic on a lawnmower. Flying requires different kinds of special-purpose machines.

Some devices are more versatile because they are simple. A sharpened stick, for example, can be used as a lever, or to cook a kebab, or to knit a sweater. Indeed, more uses can probably be found for a simple sharpened stick than for a Victorinox Pocket Size MiniChamp II my top-of-the-range Swiss knife. Yet, despite their varying versatility, Swiss Army knives, lawnmowers and sharpened sticks are all a similar sort of machine. Even the knife and the stick are, in the end, special-purpose machines, and are radically different to an astonishing device built for the first time in the middle of the last century: a machine of universal application.

An early example could be found in Manchester in 1951. It filled a room, and broke down regularly. A team of engineers tended it, replacing the valves or vacuum tubes as they blew. They called it the Blue Pig. If you had 150,000 you could buy one of these machines for yourself, although there would be a queue of military establishments and scientific laboratories ahead of you. Three years earlier, the first ever machine of this type had been built a hundred yards away. That one was an experiment, rows of electronic tubes and a tangle of gutta-percha-covered wires filling what resembled a set of bookshelves. The 1951 model gleamed the valves hidden in banks of metal cupboards, a shiny central console with rows of switches and lights.

Late in the year, the Blue Pig had some visitors. They were from a childrens radio programme, and had come to hear the Pig sing. The engineers prepared the machine, and, after a moments hesitation, a gratingly harsh but stately National Anthem blared forth. The radio presenter was delighted. The patriotic hymn was followed by Baa Baa Black Sheep and finally the dancehall jazz of In the Mood. The Blue Pig had trouble with the last tune: it improvised some notes of its own and then fell into silence. The machine, concluded the radio presenter, was not, after all, in the mood.

With the visitors gone, the engineers returned to another task, but with the same machine. The Pig could produce poetry, doggerel love letters. Heres an example:

Darling Sweetheart,

You are my fellow feeling. My affection curiously clings to your passionate wish. My liking yearns to your heart. You are my wistful sympathy: my tender liking.

Yours beautifully

M.U.C.

The Blue Pig could do mathematics too. Much faster than any human mathematician, it made calculation after calculation. What it searched for were moments when a certain function the Riemann Zeta function took the value of zero. It was something of a fishing expedition, but if they were lucky and found an unexpected zero, then a famous mathematical hypothesis would be proven wrong. Despite the Pigs all-night efforts, none was found. This was a particular disappointment to a middle-aged man of awkward manner, who had achieved early fame proving another hypothesis wrong and at the very same moment had come up with the idea now expressed in massive material form by the Blue Pig. This man was Alan Turing, and the renaissance Pig one machine producing music, poetry and mathematics was MUC: the Manchester University Computer.

Computers nowadays look nothing like the Blue Pig. But the machine that sits on your desk shares the same ability as its predecessor from half a century ago: it is a universal machine. I use mine to write books, send e-mails, play music and add numbers. Without it Id need a typewriter, a pen, paper, envelopes, a CD player and a calculator. If I stuck all these special-purpose objects together Id have something akin to a very strange Swiss Army knife, but it wouldnt be a computer. A computer can switch between these different jobs, while apparently remaining the same machine. It is a different sort of device from the special-purpose machines.

What makes the difference is the fact that a computer has two parts: a part which does stuff, and a part which has a list of instructions of what stuff to do next. It is the fact that we can change the list of instructions that makes the computer a different sort of device from a typewriter or a calculator. In other words, the computer can store and run a program.

There is another sense in which computers in the twenty-first century are universal machines: they seem to be everywhere. Not only do they sit atop millions of desks in every city, but they also come in many sizes and shapes. Laboratories such as CERN on the SwissFrench border or Los Alamos in New Mexico, where thousands of scientists congregate, depend on massive, powerful computers, each of which might cost as much as a new hospital. These machines are bigger and pricier than the Blue Pig. However, the drop in the cost of computing in the twentieth century was something unprecedented in the history of technology. As one chief executive put it: if the performance and cost of the car had followed that of the computer, we would be driving to Mars on a thimbleful of gasoline. The reason for this remarkable transformation is miniaturisation: by the 1970s a whole computer could be put on one small chip of silicon, a microprocessor. Thats a Blue Pig sitting on something the size of a postage stamp.

As a result of this miniaturisation, computing has become too cheap to meter. Take, for example, a washing machine. By the late nineteenth century there was already a range of special-purpose machines to help clean clothes, including two important ones. First, a big vat in which clothes could be soaked, soaped and stirred. Using the vat, you got clean but wet clothes. Second, a mangle, which consisted of two rollers attached to a handle. You fed the clothes between the rollers and cranked the handle to squeeze out the water, and the end result was clean and almost dry clothes. It was back-breaking work for a human: stirring, lifting and cranking. Then the washing machine added another device an electric motor and changed how the work was done. Think carefully about what has happened. Now you just put the clothes into a washer-dryer, press a button, wait, and ideally take out clean, dry clothes. To do this, the machine has to have parts which clean and parts which dry. However, in any piece of work something else must be clear too: knowledge of the order in which to perform the stages of the work. Or, in other words, any job can be expressed as a list of instructions. The list that a washing machine has to follow is not very long, nor very complicated. However, in a modern washing machine this list is programmed into a microprocessor. We know that a computer can follow any list of instructions as long as they are put in a form that it can understand. It is an indication of just how cheap computers have become that we now put them in washing machines. The microprocessor of a washing machine governs the order of rinses and spins. The miniature embedded computers found in modern cars monitor the engine, keep track of fuel consumption, and control the information displayed on the dashboard. Even the roads that the car travels upon are getting smarter: microprocessors control the traffic lights, the hazard warning signs, the speed cameras, and the electronic panels which flash up the number of free parking spaces in the city centre. Electronic information is constantly circulating in the modern world, a flow enabled by millions of miniature computers. The universal machine is not just a device of multi-purpose application, but has become ubiquitous, if often unnoticed. In the West, in the year of the Y2K scare, the average distance from every human to a computer was a matter of a handful of metres.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Turing and the Universal Machine: The Making of the Modern Computer»

Look at similar books to Turing and the Universal Machine: The Making of the Modern Computer. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Turing and the Universal Machine: The Making of the Modern Computer and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.