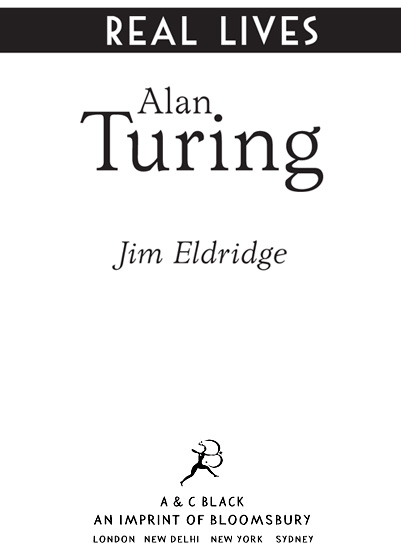

This electronic edition published in November 2013 by Bloomsbury Publishing

Copyright 2013 A & C Black

Text copyright 2013 Jim Eldridge

First published 2013 by A & C Black

Bloomsbury Publishing Plc

50 Bedford Square,

London, WC1B 3DP

www.bloomsbury.com

The right of Jim Eldridge to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyrights, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved

You may not copy, distribute, transmit, reproduce or otherwise make available this publication (or any part of it) in any form, or by any means (including without limitation electronic, digital, optical, mechanical, photocopying, printing, recording or otherwise), without the prior written permission of the publisher. Any person who does any unauthorised act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages.

eISBN: 978-1-4729-0011-1

A CIP catalogue for this book is available from the British Library.

Visit www.bloomsbury.com to find out more about our authors and their books

You will find extracts, author interviews, author events and you can sign up for newsletters to be the first to hear about our latest releases and special offers

To Lynne, my inspiration

Contents

1

School

Alan Turing was born on 23 June 1912 in London. At this time his parents lived in India because his father worked for the Indian Civil Service, and soon after Alan was born, his parents returned there. They left their two sons in the care of friends of the family, Colonel and Mrs Ward, who became the boys foster parents.

This was not unusual for the time. Many British families who worked in India, or other parts of the British Empire, sent their children back to England to be educated, returning occasionally to visit.

Colonel and Mrs Ward lived in St Leonards-on-Sea near Hastings, in Sussex. The upbringing of Alan and his brother was left in the hands of Mrs Ward, but in reality they were brought up by their nanny, who they called Nanny Thompson.

Alan wasnt happy at the Wards: they thought he was a bookish child, rather than an active one, and they disapproved of this. Mrs Ward complained to Alans mother about this side of him, and Mrs Turing wrote to Alan from India telling him off for being too much of a bookworm.

When Alan was ten, he was sent to Hazelhurst, a small prep school for boys. It was while Alan was there that Julius Turing decided to take early retirement from the Indian Civil Service, and Mr and Mrs Turing moved to the town of Dinard in Brittany in northern France. The plan was for Alan and John to live with their parents in Brittany during school holidays, and return to England during term time to go to school, where they would be boarders (living at the school).

In 1926, Alan sat the entrance exam for a place at Sherborne School. Admission to this prestigious public school was highly competitive. Alan passed the exam and won a place.

In September 1926, Alan, then aged 14, caught the boat from Brittany to Southampton in England, travelling on his own. When he arrived in Southampton there was a General Strike in Britain, which meant there were no trains, no buses, no public transport of any kind. So Alan collected his bicycle from the boat, bought a map, and then cycled the sixty miles from Southampton to Sherborne. On the way he had problems with his bicycle and had to stop to carry out repairs to it, which meant he had to stay overnight at a hotel. Despite this, he cycled in through the gates of Sherborne School in time for the start of school. Being a methodical boy, he posted the receipts for his expenses on his journey to his father in France, asking him to send him the money.

Even at this young age, Alan Turing was a determined person, set on overcoming all obstacles to achieve his aims.

Alans time at Sherborne was not particularly happy. As at most British public schools at this time, the academic emphasis was on the Classics (Latin and Greek), and on the arts, particularly literature. Sports were also an important feature of school life. Subjects such as sciences and mathematics were looked down on as inferior pursuits. Alan did not enjoy English and Latin: he was bottom of his class in English, and second from bottom in Latin. His handwriting was messy and often illegible. He could not stop his pen from leaking ink and making ink blots on his work. Fellow pupils remembered him as a messy and untidy boy, sometimes stammering when he spoke.

One report from his teacher was very blunt in its disapproval of him, stating, His writing is the worst I have ever seen. His work is slipshod, dirty and inconsistent.

It was hardly an inspiring start for someone who would later be considered to be one of the twentieth centurys greatest geniuses.

When it came to sports, Alan did not enjoy team games, although he did enjoy solo long-distance running. It was while he was at Sherborne that Alans talent as a runner came out, and he won races both at Sherborne and in athletics competitions held against other schools.

Even in mathematics, for which he had shown a great aptitude, Alan had trouble at Sherborne. For one thing, he struggled with long division; but his biggest problem was that he solved mathematical problems without doing any of the early stages that were required: he went straight to the end and reached the correct conclusion without showing how he had arrived at that conclusion. His teachers complained that his work at maths was not methodical. This was seen as very bad: the approved method of working out a maths problem was to build up a proof step by step. Because of this, his work was marked down, and he did badly in maths tests at school.

As far as we know, Alan responded to this with a mixture of annoyance and frustration. He did the work and understood it as well as anyone. When it came to solving mathematical problems, he did not understand why his teachers could not see that he did not need to work out the answer by a long and tedious method, when the correct answer simply leapt out at him. Already, Alans different way of thinking, a kind of lateral way of working out problems, was showing itself.

Some teachers at the school did see Alans potential, particularly the chemistry teacher. Chemistry was one of Alans favourite subjects, and he spent many hours conducting chemistry experiments. In one of these, when he was just 14, he worked out a new method for extracting iodine from seaweed.

It was at Sherborne that Alan finally found a friend he felt comfortable with. Up until the time he met Christopher Morcom, Alan had been a lonely, solitary child, considered anti-social and, because of that, odd. Christopher was a year older than Alan but they were on the same wavelength: both were excited by the mysteries of chemistry and other sciences, as well as enjoying the more complex forms of maths. Alan and Christopher spent a lot of their time discussing Einsteins theories, and working out their own answers to problems that the scientific community were grappling with.

In December 1929, Christopher sat the entrance exam to go to Cambridge University. Alan was keen to go to Cambridge at the same time as Christopher, and also sat the entrance exam, although he was just 17 years old. Christopher passed, his scores being high enough to earn a scholarship. Alan failed, which meant he would have to remain for a further year at Sherborne.

2

Cambridge University

On 6 February 1930, Christopher Morcom became dangerously ill and was rushed to hospital. He was suffering from a recurrence of bovine tuberculosis, the result of drinking contaminated cows milk many years earlier. On 13 February, Christopher died.

Next page