Also by PAUL GARSON

New Images of Nazi Germany: A Photographic Collection (McFarland, 2012)

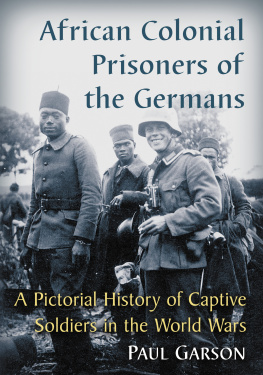

African Colonial Prisoners of the Germans

A Pictorial History of Captive Soldiers in the World Wars

Paul Garson

McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers

Jefferson, North Carolina

e-ISBN: 978-1-4766-2542-3

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGUING DATA ARE AVAILABLE

BRITISH LIBRARY CATALOGUING DATA ARE AVAILABLE

2016 Paul Garson. All rights reserved

No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying or recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

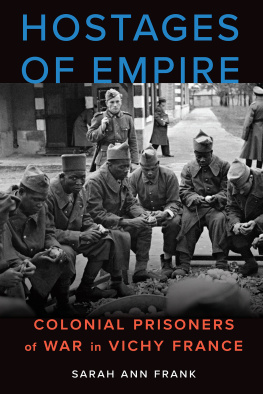

Front cover: A German NCO in the Wehrmacht poses for a photograph with his French African colonial captives somewhere in France in the summer of 1940 (Authors collection)

McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers

Box 611, Jefferson, North Carolina 28640

www.mcfarlandpub.com

Preface

In the time when Dendid created all things,

He created the sun,

And the sun is born, and dies, and comes again.

He created the moon,

And the moon is born, and dies, and comes again;

He created the stars,

And the stars are born, and die, and come again;

He created man,

And man is born, and dies, and does not come again.

Ancient song of the Dinka tribe of the Southern Sudan

The fate of African colonial soldiers during the World War I and II was inextricably linked both to European imperialism and its racist foundations. Measured as a currency of blood and lives lost, the recruits served foreign masters who regarded them as a manpower resource available for consumption just as those same foreign masters had extracted other raw materials from their African colonies.

Among those non-European military resources procured from Frances colonial empire were soldiers of some 23 nationalities who would bear arms during World War II in the battle against the Nazi invaders. By August 1944, following the June 6th Allied D-Day amphibious landings, half the Free French forces that landed on the beaches of Normandy were Africans.

Prior to Germanys invasion of France in the summer of 1940, few of the new generation of German soldiers taking part in the campaign, especially those who lived outside metropolitan centers such as Berlin, had ever seen, much less interacted with, a black person. German forces, when encountering these soldiers of color, reacted with a variety of responses, from curiosity to murderous intent. Often they considered their encounters with African soldiers a novelty, worth recording for family and friends back home. Since many German soldiers brought their personal cameras to the battlefront, the snapshots they captured helped document the outcomes of these encounters.

This book takes us into one of those cul-du-sacs of war, one largely overlooked, that of the German militarys treatment of African colonial soldiers. Not only did their German enemies regard the African colonial soldiers as culturally inferior, but in great part so did their French military overseers who shipped them en masse from their homes in Africa to fight and die in yet another European war.

Notes on the Photographs, Artifacts and Documents

Many of the 20,000,000 Germans in Third Reich uniforms recorded their military experiences on film, often using advanced German cameras. In addition, the Nazi regimes massive propaganda apparatus produced millions of images to promote their programs, foster public support and bolster morale.

Tourists.A group of German army soldiers capture images of a days outing cameras, swords and bayonets included.

German army officers adjust a variety of still and motion picture cameras somewhere in France.

All the images in this book are originals from the authors collection and are for the most part one-of-a-kind photos taken by individual German soldiers. They constitute part of an archive of some 3,000 photographs, postcards, documents and artifacts sourced from around the world. Many more such photographs exist, now and then resurfacing after decades. When they do reappear they continue to shed light on that darkest of times where technology and racism took warfare to a new level of barbarityin the process creating indelible images of a war that forever changed humankinds view of itself.

While many of these images captured by the German servicemens cameras are telling in and of themselves, some carried explanatory handwritten notations or were captioned in some way when they were placed in often elaborately detailed service albums. While the notes are often illegible, thus most remaining anonymous, a very few have provided a particular name, place and date.

With their presentation within the historical context, the author hopes the photos will bring forth some form of recognition, perhaps even allowing for attachment of a name to some of the many faces who for decades have remained unnamed. When viewing these images, one must also keep in mind that an individual, in this case a German soldier, had made a conscious decision to aim his personal camera at a particular target. So in effect the images are two-sided, the photographer an unseen reflection in the eye of the subject; both fused together for a uniquely recorded split second of history.

Introduction

Before the Germans Invade France, the French Invade Africa

The so-called Army of Africa (Arme dAfrique) initially took shape in 1830 when France began accepting volunteers from its colonial possessions in Morocco, Algeria and Tunisia. The Tirailleurs, comprised of indigenous colonial French Africans, were first formed in 1841 in French colonial Algeria and three years later the 4th Regiment was formed in Tunisia. The Tirailleurs Sngalais (skirmishers or riflemen) were first formed in 1857 by Louis Faidherbe, governor general of French West Africa who went seeking soldiers who, unlike white Europeans, would be immune to malaria and other indigenous diseases.

The numbers of recruits increased after conscription was implemented in 1913 as the result of the impending European conflict. At the outbreak of World War I, the Army of Africa was comprised of 28 regiments of Algerian Tirailleurs, 13 regiments of Zouaves (light infantry), six of Chasseurs (mounted cavalry), and four regiments of Spahis (horsemen). They were joined in 1914 by the 1st Regiment of Moroccan Tirailleurs.

During World War II the various colonial troops, known overall as Tirailleurs, were similarly recruited from the northwest region of African known as the Maghreb (Maghrib) and included indigenous peoples from Algeria, Morocco, Tunisia, French West Africa and Madagascar. Elements of the famed French Foreign Legion, its members sourced from a wide range of countries, were also considered part of the Army of Africa.

Next page