DECISION AT ANTIETAM

A counterfactual history of the Civil War

Andrew J. Heller

Copyright 2018 Andrew J. Heller

The right of Andrew J. Heller to be identified as author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988

All Rights Reserved

No reproduction, copy or transmission of the publication may be made without written permission. No paragraph of this publication may be reproduced, copied or transmitted save with the written permission of the publisher, or in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright Act 1956 (as amended).

Any person who does any unauthorised act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages.

Published by

Fiction4All

www.fiction4all.com

This Edition Published 2018

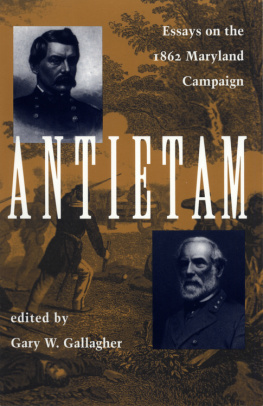

Cover image from print

Battle of Antietam

by

Thure de Thulstrup

(1887)

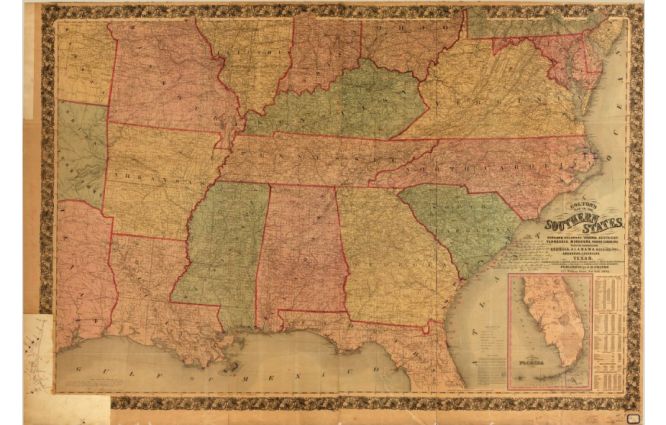

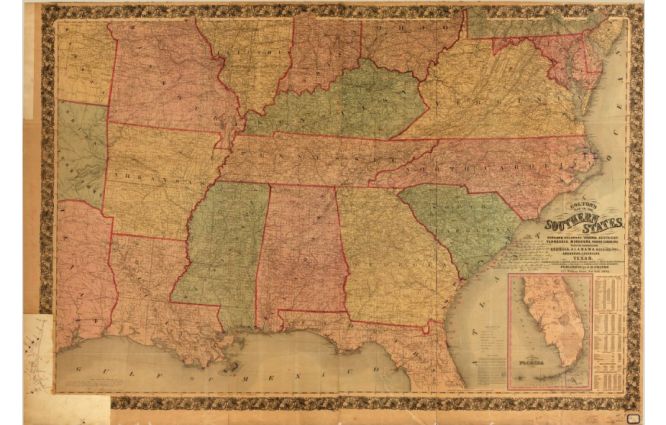

The Southern States on the eve of the Civil War

Introduction

The American Civil War is by all odds the most popular subject of alternate history fiction, as it is the most popular subject of straight history in the United States. That popularity is doubtless related to the fact that there are many people in this country who remain unreconciled to the result, even in the 21 st Century. This phenomenon has actually grown in both scope and seriousness.

Many novels have been written in which the South was victorious. Until recently, the majority of them were simply dedicated to showing that Lee, Jackson, Stuart and their men were better than the Yankees, and deserved to win. In other words, they were for the most part, fairly harmless hero-worship.

Within the last 20 years or so, things have changed. A considerable number of revisionist histories of the Civil War by alleged scholars have been published purporting to show that, among other things, secession had nothing to do with slavery, the war was entirely the result of Northern aggression, secession was justified by intolerable oppression of the South by the Federal government, and similar, equally dubious propositions.

This has in turn resulted in a series of new, openly political alternate histories of the Civil War which echo the afore-mentioned scholarly histories. These new alternate histories tend to be more strident in their claims of Confederate superiority, to the extent that they begin by assuming that the South would certainly have won the war, if not for bad luck, such as the accidental shooting of Stonewall Jackson by his own men at Chancellorsville.

My purpose in writing this book is to show be means of a counter-factual thought experiment that if anything, the South was very fortunate to avoid being defeated much more quickly than it was in fact, by use of a serious counterfactual analysis. The book begins by looking at what very nearly happened the Battle of Antietam, then goes on to set forth some of the consequences that would have been likely to flow from what was initially only a very slight alteration in events (the late arrival of A.P. Hill at Sharpsburg). I have made every effort to base my conclusions on reliable historical sources, and have done my best to set aside any preconceptions I may have had, although I cannot promise that I was completely successful with the latter.

I do not believe it is necessary to further prove that the Confederate cause was, in the words of Ulysses S. Grant, the worst one men ever fought for, nor is this the place for it. My purpose here is to show that the South was, rather than the victim of unusually bad luck, the beneficiary of undeserved good fortune, and to offer a plausible example of how the war could have easily gone very much worse for the Confederacy than it did in fact.

This book was originally published as part of a novel entitled If the North Had Won the Civil War , which was set in a 21 st Century CSA. In retrospect, my counterfactual history may have been overlooked by serious students of the Civil War, because it was presented intermingled with this novel. So for those of you who like your counterfactuals straight with no chaser, I give you Decision at Antietam .

In addition to some comparatively minor textual changes and corrections, there is one major change to the original material. I had accumulated many contemporary photographs of the (real) people places and things in the book, as well as a number of maps, none of which were in If the North Had Won the Civil War . I have taken the opportunity presented by the publication of this book to include them here, and I think addition represents a significant improvement over the original presentation. All illustrations are in the public domain courtesy of the Library of Congress, unless otherwise noted.

Andrew J. Heller

May, 2018

Erdenheim, PA

Table of Contents

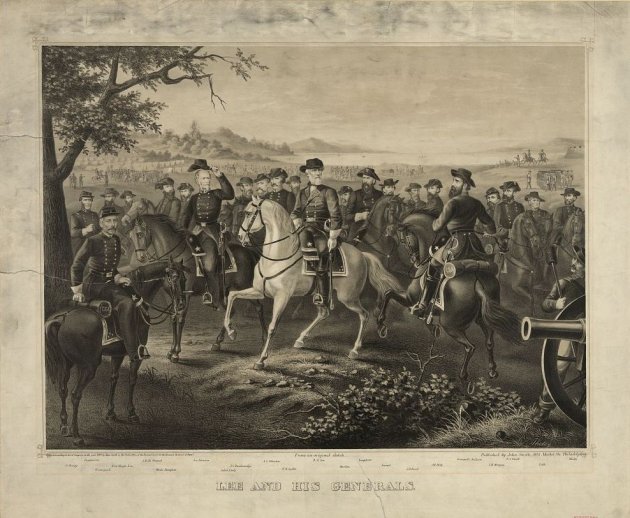

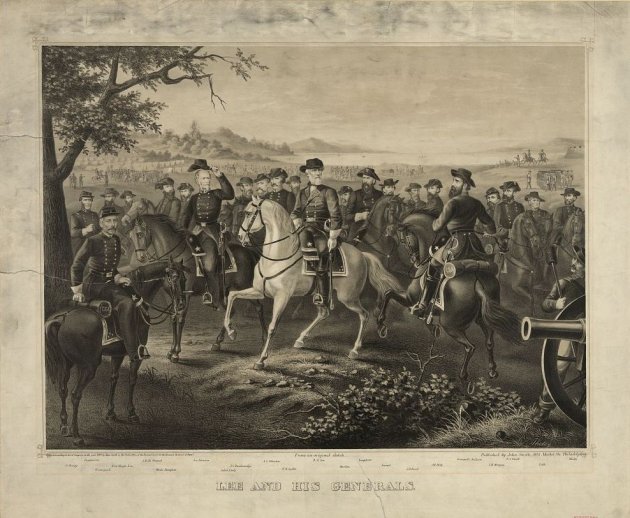

Robert E. Lee and his staff

Chapter One

A most terrible sight

Robert E. Lee began his invasion of Maryland in 1862 as he began all of his campaigns, with one goal in mind: to engage and destroy the enemy army in a single great battle:- in short, to recreate Napoleons victory at Austerlitz.

The trait that made Lee notable among military men of his time and place was not his obsessive quest for a Napoleonic, war-winning victory in battle (this was typical of West Point graduates of his era), but rather his willingness to take long chances to achieve one. Napoleons Grand Army almost always had numerical superiority and other tactical advantages over its foes in its great victories, particularly in artillery. Lees Army of Northern Virginia, on the other hand, was invariably outnumbered by its opponents, and if the Rebels possessed superiority in the cavalry arm, this was more than offset by the quality and quantity of the superb Federal artillery.

So in order to create the conditions for his Austerlitz, Lee had to take chances, sometimes what seemed like desperate chances. Like a professional riverboat gambler ready to risk his entire fortune on the turn of a card, Lee was willing to play with the highest stakes for the biggest prize, a war-winning battle of annihilation. While conventional military wisdom held that offensive action requires a manpower advantage of at least 3 to 2 in favor of the attacker, Lee repeatedly demonstrated his readiness to strike at the enemy in an attempt to bring about a battle of annihilation, undeterred by the fact that he was usually on the short end of 3 to 2 odds or worse.

Lee set the tone for his aggressive style of command in the first battle of the Seven Days, at Mechanicsville, by dividing his forces in the face of the much larger Union army in order to go over to the offensive. He left only 25,000 men in the Richmond defenses to face approximately 3 times as many Federals, while he shifted the bulk of his army across the Chickahominy Creek to gain local superiority, risking the loss of the Confederate capitol and possibly the war itself in an attempt to destroy the Union right wing.

When this blow went awry, he continued to attack the Federal army over the course of the following week, as if he had 105,000 men and the enemy 85,000, instead of the reverse. In the end, Lee was dissatisfied with merely defeating and driving off the bigger Union army, and saving Richmond. After the Seven Days, he wrote, Under ordinary circumstances, the Federal Army should have been destroyed. Soon thereafter, Lee pushed all his chips in with another attempt to win the big pot, when he divided his army in the face of the enemy yet again, to bamboozle Pope and smash his army at Second Manassas.