ALSO BY GEORGE PACKER

Nonfiction

The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New America

Interesting Times: Writings from a Turbulent Decade

The Assassins Gate: America in Iraq

Blood of the Liberals

The Village of Waiting

Fiction

Central Square

The Half Man

Plays

Betrayed

As Editor

All Art Is Propaganda: Critical Essays

by George Orwell

Facing Unpleasant Facts: Narrative Essays

by George Orwell

The Fight Is for Democracy:

Winning the War of Ideas in America and the World

THIS IS A BORZOI BOOK

PUBLISHED BY ALFRED A. KNOPF

Copyright 2019 by George Packer

All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Alfred A. Knopf, a division of Penguin Random House LLC, New York, and distributed in Canada by Random House of Canada, a division of Penguin Random House Canada Limited, Toronto.

www.aaknopf.com

Knopf, Borzoi Books, and the colophon are registered trademarks of Penguin Random House LLC.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Packer, George, [date] author.

Title: Our man : Richard Holbrooke and the end of the American century / by George Packer.

Other titles: Richard Holbrooke and the end of the American century

Description: First edition. | New York : Alfred A. Knopf, [2019] | A Borzoi book. | Includes bibliographical references.

Identifiers: LCCN 2018030382 (print) | LCCN 2018031100 (ebook) | ISBN 9780307958037 (ebook) | ISBN 9780307958020 (hardcover)

Subjects: LCSH : Holbrooke, Richard C., 19412010. | DiplomatsUnited StatesBiography. | AmbassadorsUnited StatesBiography. | StatesmenUnited StatesBiography.

Classification: LCC E 840.8. H 64 (ebook) | LCC E 840.8. H 64 P 33 2019 (print) | DDC 320.092 [ B ]dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018030382

Ebook ISBN9780307958037

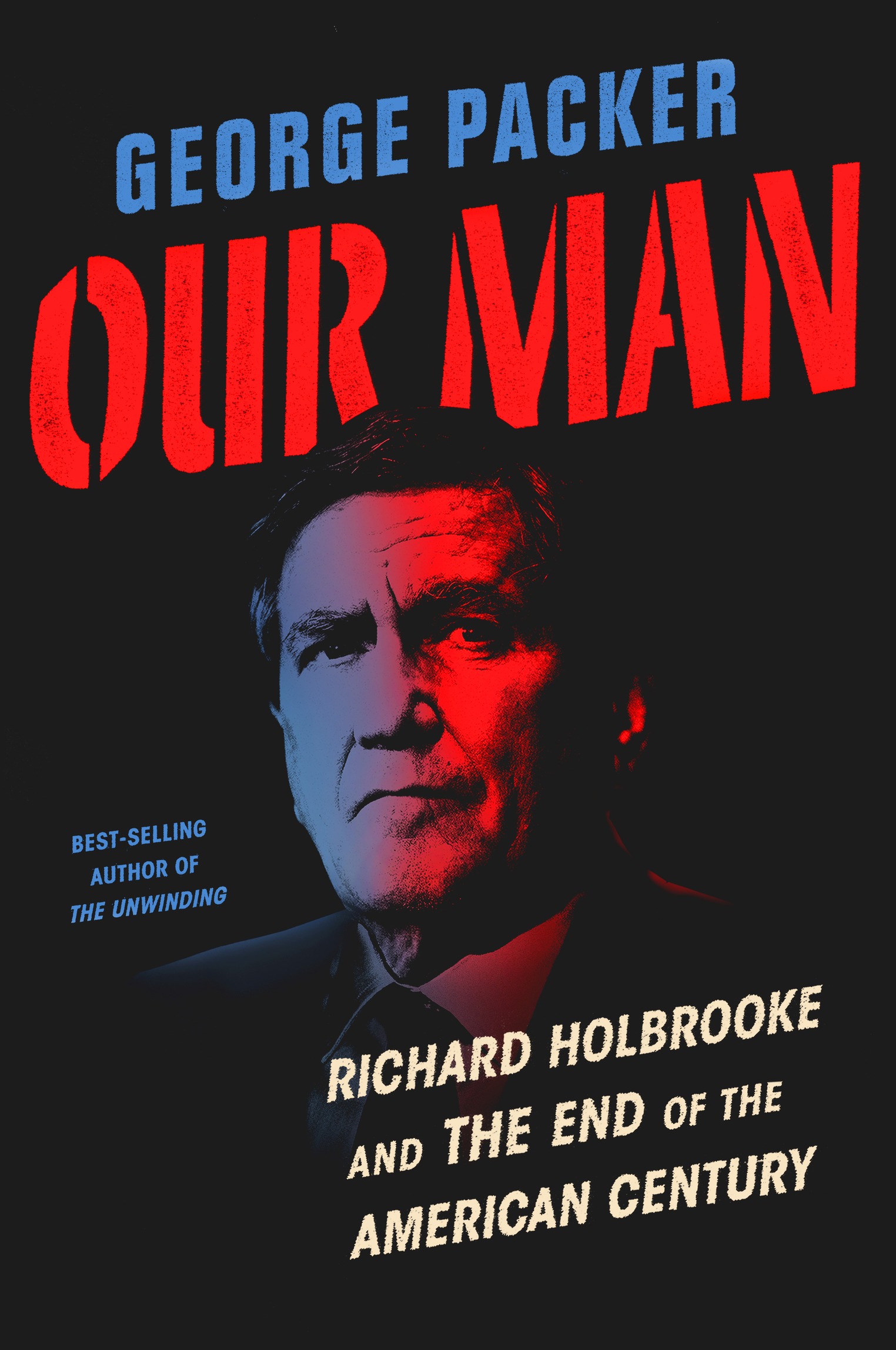

Cover photograph by Alex Wong / Getty Images

Cover design by Tyler Comrie

v5.4

ep

For Les and Judy Gelb

and for Frank Wisner

Contents

Holbrooke? Yes, I knew him. I cant get his voice out of my head. I still hear it saying, You havent read that book? You really need to read it. Saying, I feel, and I hope this doesnt sound too self-satisfied, that in a very difficult situation where nobody has the answer, I at least know what the overall questions and moving parts are. Saying, Gotta go, Hillarys on the line. That voice! Calm, nasal, a trace of older New York, a singsong cadence when he was being playful, but always doing something to you, cajoling, flattering, bullying, seducing, needling, analyzing, one-upping youapplying continuous pressure like a strong underwater current, so that by the end of a conversation, even two minutes on the phone, you found yourself far out from where youd started, unsure how you got there, and mysteriously exhausted.

He was six feet one but seemed bigger. He had long skinny limbs and a barrel chest and broad square shoulder bones, on top of which sat his strangely small head and, encased within it, the sleepless brain. His feet were so far from his trunk that, as his body wore down and the blood stopped circulating properly, they swelled up and became marbled red and white like steak. He had special shoes made and carried extra socks in his leather attach case, sweating through half a dozen pairs a day, stripping them off on long flights and draping them over his seat pocket in first class, or else cramming used socks next to the classified documents in his briefcase. He wrote his book about ending the war in Bosniathe place in history that he always craved, though it was never enoughwith his feet planted in a Brookstone shiatsu foot massager. One morning he showed up late for a meeting in the secretary of states suite at the Waldorf Astoria in his stocking feet, shirt untucked and fly half zipped, padding around the room and picking grapes off a fruit basket, while Madeleine Albrights furious stare tracked his every move. During a videoconference call from the U.N. mission in New York his feet were propped up on a chair, while down in the White House Situation Room their giant distortion completely filled the wall screen and so disrupted the meeting that President Clintons national security advisor finally ordered a military aide to turn off the video feed. Holbrooke put his feet up anywhere, in the White House, on other peoples desks and coffee tablesfor relief, and for advantage.

Near the end, it seemed as if all his troubles were collecting in his feetatrial fibrillation, marital tension, thwarted ambition, conspiring colleagues, hundreds of thousands of air miles, corrupt foreign leaders, a war that would not yield to the relentless force of his will.

But at the other extreme from his feet, the ice-blue eyes were on perpetual alert. Their light told you that his intelligence was always awake and working. They captured nearly everything and gave almost nothing away. Like one-way mirrors, they looked outward, not inward. I never knew anyone quicker to size up a room, an adversary, a newspaper article, a set of variables in a complex situationeven his own imminent death. The ceaseless appraising told of a manic spirit churning somewhere within the low voice and languid limbs. Once, in the 1980s, he was walking down Madison Avenue when an acquaintance passed him and called out, Hi, Dick. Holbrooke watched the man go by, then turned to his companion: I wonder what he meant by that. Yes, his curly hair never obeyed the comb, and his suit always looked rumpled, and he couldnt stay off the phone or TV, and he kept losing things, and he ate as much food as fast as he could, once slicing open the tip of his nose on a clamshell and bleeding through a pair of cloth napkinsyes, he was in almost every way a disorderly presence. But his eyes never lost focus.

So much thought, so little inwardness. He could not be alonehe might have had to think about himself. Maybe that was something he couldnt afford to do. Leslie Gelb, Holbrookes friend of forty-five years and recipient of multiple daily phone calls, would butt into a monologue and ask, Whats Obama like? Holbrooke would give a brilliant analysis of the president. How do you think you affect Obama? Holbrooke had nothing to say. Where did it come from, that blind spot behind his eyes that masked his inner life? It was a great advantage over the rest of us, because the propulsion from idea to action was never broken by self-scrutiny. It was also a great vulnerability, and finally, it was fatal.

I can hear the voice saying, Its your problem now, not mine.

He loved speed. Franz Klammers fearless downhill run for the gold in 1976 was a feat Holbrooke never finished admiring, until you almost believed that he had been the one throwing himself into those dangerous turns at Innsbruck. He pedaled his bike straight into a swarming Saigon intersection while talking about the war to a terrified blond journalist just arrived from Manhattan; he zipped through Paris traffic while lecturing his State Department boss on the status of the Vietnam peace talks; his Humvee careered down the dirt switchbacks of the Mount Igman road above besieged Sarajevo, chased by the armored personnel carrier with his doomed colleagues.

He loved mischief. It made him endless fun to be with and got him into unnecessary trouble. In 1967, he was standing outside Robert McNamaras office on the second floor of the Pentagon, a twenty-six-year-old junior official hoping to catch the secretary of defense on his way in or out, for no reason other than self-advancement. A famous colonel was waiting, tooa decorated paratrooper back from Vietnam, where Holbrooke had known him. Everything about the colonel was pressed and creased, his uniform shirt, his face, his pants carefully tucked into his boots and delicately bloused around the calves. He must have spent the whole morning on them. That looks really beautiful, Holbrooke said, and he reached down and yanked a pants leg all the way out of its boot. The colonel started yelling. Holbrooke laughed.