Introduction

T his book contains a selection of stories from Irish history. Some are more famous than others while most have been forgotten, but even those that are better known are often only partially understood. For example, many people would know that Myles Keogh fought and died at the Battle of the Little Bighorn but his involvement in the battle is shrouded in myth and legend. Also, until this book, nothing had ever been written about the more than 100 other Irish soldiers who fought at the battle. Major figures such as John Barry, who played an important role in the American War of Independence, and John Philip Holland, a key inventor of the modern submarine, have had hardly a word devoted to them in recent decades.

The same can be said of the almost unknown story of the Irish battalion in the Papal army of 1860, while the epic histories of the Irish who fought for both the Union and the Confederacy during the American Civil War are better known in America than in Ireland. Other stories are also more famous internationally than in Ireland. Such is the case with the thrilling tale of the San Patricios and the brutal MexicanAmerican War of the 1840s. It is also true of John Henry Pattersons long struggle against the Tsavo lions in what is modern-day Kenya. Even events such as the Connaught Rangers Mutiny exist mostly in out-of-print books or the pages of old newspapers. Also, there are events at home of crucial importance to modern Irish history whose history has only been partially written. There is no single account of Dublins Bloody Sunday in 1920 that covers all of the days events, including vital new evidence on the violence at Croke Park.

These are Irish stories, but they also provide a glimpse of how the history of the Irish has intersected with that of other peoples and other countries. The stories are also American, British, Mexican, Italian, Native American, African and Indian; and, as this list suggests, much of the warfare conducted by the Irish has been fought abroad. Consequently, all but one of the chapters in the book takes place outside Ireland.

Many of the stories involve Irish emigrants. Dispossessed and oppressed for much of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, it is no surprise that so many Irish people ended up fighting in other peoples wars. For many Irishmen, especially emigrants and the rural and urban poor, a career as a soldier was the last best hope for a better life and the great armies of the world have always been a home to those on the bottom rungs of society. Other stories in the book involve career soldiers, but the book is not an exhaustive study of the Irish at war. It is based around extraordinary people and events that I have stumbled upon over the years and is an assorted mix of revolutionaries, inventors, soldiers, sailors and mutineers. These stories have interested me and I hope that they interest you.

I would like to thank my brother, Enda, who acted as my research assistant and who conducted research in both Ireland and the United States. He, as well as my partner, Fiona, read the manuscripts and provided advice. I would also like to thank my father Joe, Billy Phillips and Dr Gerald Naughton for reading sections of the manuscript and for their advice. As much as I would like to blame them, any errors, omissions or misinterpretations are my fault.

Thanks to The Collins Press and especially my editor Cathy Thompson. Her work has greatly improved the book. I much appreciate the help given to me by the library staff of National University of Ireland, Galway; the staff of the National Library in Dublin; the staff of the Croke Park GAA Museum; and the staff of the Military Archives at Cathal Brugha Barracks. Thanks also to Pat Sweeney of the Maritime Institute of Ireland, who provided me with information on John Philip Hollands early life in Clare. In the US, I owe thanks to the staff in Boston College and Boston University, the staff at the Field Museum of natural history and the US Library of Congress, as well as the numerous other museums and libraries where my brother conducted research.

I would like to thank my parents, Mary and Joe, my sister Aoife and my family in Cork. I would also like to thank all the Lynams, including Conor, Mary and especially Risn, who acts as my unofficial publicity agent in the midlands. Finally, thanks to Fiona for all her love and support.

1

John Barry (17451803): Father of the

United States Navy

He was born in the county of Wexford in Ireland

But America was the object of his patriotism

And the theatre of his usefulness.

In the Revolutionary War which established the

Independence of the United States he

Bore an early and active part as a captain in their

Navy and after became its Commander-in-Chief.

He fought often and once bled in the Cause of Freedom.

(An extract from Barrys original epitaph, written by Dr Benjamin Rush,

a signatory of the American Declaration of Independence)

T he details of John Barrys early life are known only in outline. Born in 1745, he was the son of tenant farmers James and Ellen Barry, living and working in Ballysampson, County Wexford. Evidently it was a hard life and, when he was a child, his family suffered the trauma of eviction from their land. Moving to Rosslare, Barry found work with his uncle, Nicholas Barry, the captain of a small fishing boat. As a fisherman working in a county with a proud maritime tradition, Barry fell in love with the sea. How and when Barry left Ireland is unknown, although the most common tradition is that when he was only fifteen he set sail on a ship bound for Jamaica, from where he travelled to Philadelphia in late 1760. Another version states that he was the second mate of an Irish ship that arrived in Philadelphia in 1762.

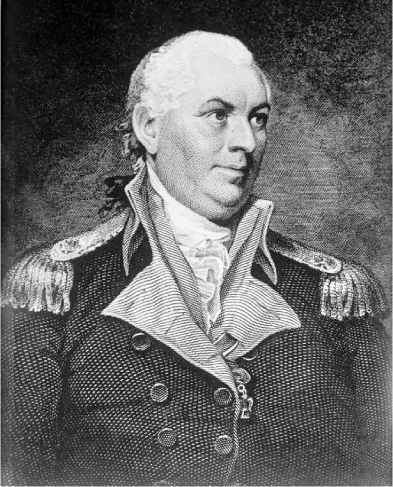

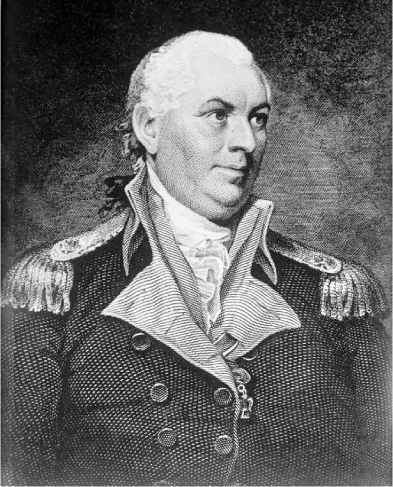

A sketch of John Barry copied from a painting by the portraitist Gilbert Stuart (Courtesy of the United States Library of Congress).

Whichever story is correct, it is known that Barry found himself alone in the New World and that he re-established contact with his family once he got to America (he wrote letters home throughout his remarkable career but, regrettably, these do not seem to have survived). He could not have realised when he looked ahead to his new life that news from Britain would set in motion a chain of events that would determine so much of his later life, as well as the course of world history.

T HE A MERICAN C OLONIES

By 1763 the thirteen British Colonies of North America seemed to be a secure and stable part of the British Empire. What had been a persistent French threat to British possessions on the continent had been ended by the Seven Years War, in which Britain had defeated France and established itself as the dominant colonial power in North America. The British success, however, contained the seeds of future rancour. Freed from the threat of French intervention, the British government determined that the American Colonies would, from now on, have to pay their share of the costs involved in maintaining a British army in North America. With this aim, the government introduced the Stamp Tax in 1765, a tax on the paper required for newspapers and legal transactions.

There was furious resistance from the American populace, with public meetings and even riots across the country. More disturbingly for the British, many colonists not only opposed the tax, but also questioned the right of Britain to impose any such taxes on the American Colonies. No taxation without representation became the common cry, with the colonists arguing that the lack of American representatives in the British Parliament made the imposition of such revenue-raising taxes unconstitutional. The government continued its policy in spite of the uproar, introducing the Townshend Acts in 1767, a system of indirect trade taxes that (most significantly) affected the import of tea, among other goods. Once again there was fierce popular opposition and a boycott of British goods. In 1768 the government responded to the heightened tensions in America by greatly increasing the numbers of soldiers in the colonies.