Tilbury House Publishers

12 Starr Street, Thomaston, Maine 04861

800-582-1899 www.tilburyhouse.com

First hardcover edition November 2015

ISBN 978-0-88448-357-1

eBook ISBN 978-0-88448-416-5

Copyright 2016 Robert Booth

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

Library of Congress Control Number: 2015952705

Text designed by Janet Robbins, North Wind Design and Production

Cover designed by Jon Friedman, Frame25 Productions

Printed in the USA by the Maple Press, York, PA.

15 16 17 18 19 20 MAP 5 4 3 2 1

Show me a hero, and Ill write you a tragedy.

F. Scott Fitzgerald, from the notebooks, 1945

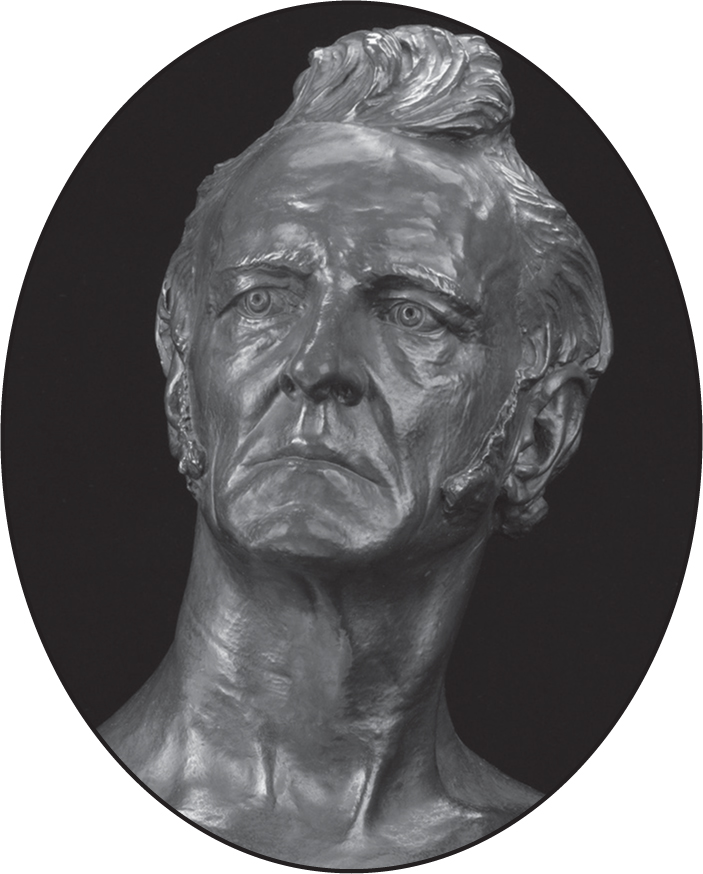

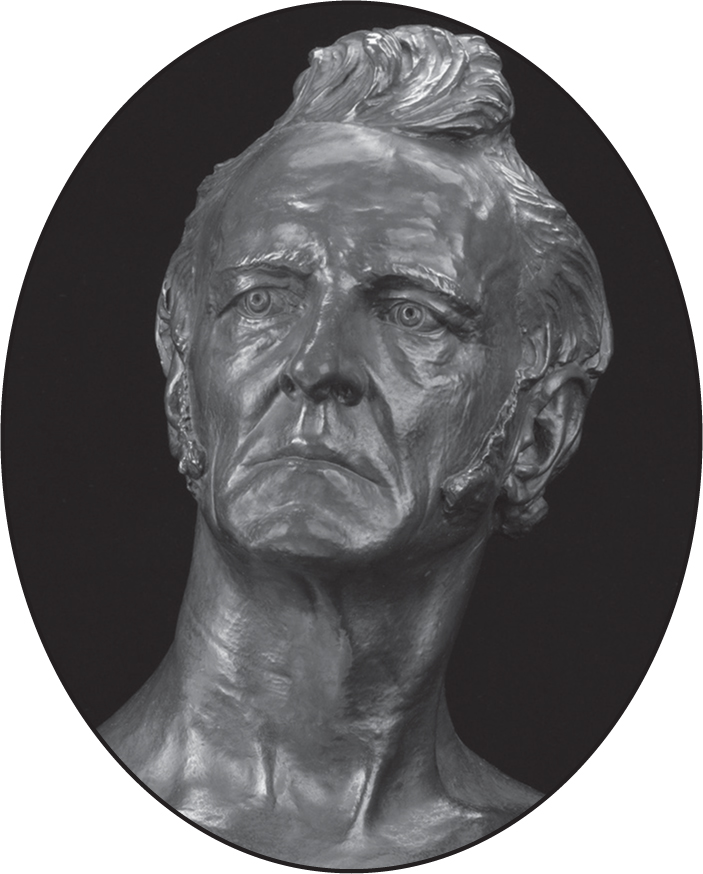

This life mask of David Porter was made in 1825, eleven years after he lost the USS Essex in the bloodiest naval fight of the War of 1812. His face still bore a large right-cheek scar earned not in battle, but in the streets of Baltimore during his escape from a mob. (Fenimore Art Museum, Cooperstown, New York; gift of Stephen C. Clark, N0215.1961; photograph by Richard Walker)

In memory of my father

Robert A. Booth

19222000

Pacific navigator, famous handicapper

Contents

Prologue

O n the afternoon of March 13, 1813, while running past a desolate stretch of Chilean shoreline, the square-rigged U.S. frigate Essex has the misfortune of losing her main topsail yard. Her captain, David Porter, intent on making an impressive entrance at the port of Valparaiso, orders his battleship hove-to.

That night, after repairs are made, the Essex rides at anchor in the gentle swells of the western ocean and Captain Porter sleeps soundly, dreaming of the British whalers that he has come so far to capture, a fleet of them, slow and awkward and full of oil, easy prey for a mighty battleship. Waking in the dark, striking a match, he is convinced that the moment has arrived. He wakes his lieutenant and gives orders, and by sunrise 300 men are at their battle stations and the Essex is bowling along under full sail.

Taking up his spyglass, Porter searches the horizon in the morning brightness, seeing only the azure line and low clouds in the distance. Confident, he keeps his vigil by the hour, until his men start muttering and his officers are exchanging glances. Finally, betrayed by his dreams and the empty sea, the scar-faced little captain gives it up and sets the Essex on a course for the coast under English colors. The mariners soon spot fishing vessels and know that they are close to their destination, but when a signal is sent aloft to summon a pilot, the local skippers stay away.

The Essex sails on, trending northeasterly. In the distance are a couple of huts and some cattle on a coast skirted by a black and gloomy rock, against the perpendicular sides of which the sea beats with fury. Farther inland, the country appears dreary beyond description: yellow and barren hills, cut by torrents into deep ravines. This stark foreground to the blank immensity of the Andes is far from Porters long-held fantasy of handsome villages and well-cultivated hills beside a beautiful blue Pacific.

Rounding the next barren bluff, the Point of Angels, Porter seeks some sign of the elusive port of the Valley of Paradise. He scans a long sandy beach, then a mule-train zigzagging its way down a hill, then in an instant afterwards, the whole townshipping with their colors flying, and the fortsburst out, as it were, from behind the rocks: Valparaiso at last.

But Porter sails too close to the cliffs, and the frigates sails luff as she suddenly decelerates. With a rush of paranoid dread, he realizes that his error has left them helpless under the guns of a battery prepared to fire into us. Seconds pass in silence as the Essex glides slowly on, until a breeze fills her topgallants and starts her back on her way. Evidently the English flag is a sufficient shield, for she sails unmolested toward an animated scene in the harbor, which includes a deep-riding American brig with her yards and topmasts struck, and a big clumsy-looking English vessel that Porter imagines to be a whaler repairing her damages after her passage around Cape Horn. Then he spots several large Spanish merchant ships preparing to depart, perhaps for Peru; if they recognize him, they might inform the English up the coast.

Porter roars at his lieutenant, John Downes, to put the helm down and send the Essex back out to sea, and in four windy hours they are thirty miles away, staring at another vista of sun-burnt hills dotted with cattle. Upon reflection, however, Porter realizes that this too is wrong. Callao, some 1,400 nautical miles norththe port for Lima, the Spanish viceroys royal capitalis the more dangerous port, so he reverses course for Valparaiso, and when the Essex reenters the bay she is flying her true colors, the Stars and Stripes.

Porter knows that the Spanish officials will not be happy. He has brought a new war with him, that of the upstart United States against Spains ally Great Britain; he is endangering the peace of Chile, a quiet country slumbering by the ocean. But he needs provisions for his 300 men and for the dozens of British sailors whom he is holding prisoner down below, some in irons.

Porter has brought his ship around Cape Horn unauthorized, bent on a private mission of wealth and glory. Ignorant of conditions in the Pacific world, he has no idea that Chile is in revolt, that its people will regard him as a savior, and that he is about to encounter the only other American official in the Pacific, Joel Roberts Poinsett, U.S. consul general for Southern Spanish America.

Chiles fateful gravity has drawn Porter and Poinsett into the presence of three other remarkable figures: Jos Miguel Carrera, the heroic leader of the revolution, seeking support for his embattled government; Jos Fernando de Abascal, the Spanish viceroy at Lima and virtual monarch of western South America, sworn to crush the rebellion; and Captain James Hillyar of the Royal Navy, sent out on pain of death to win Chile for Britain. As these men and forces converge, the longtime peace of the somnolent Pacific will be shattered, and systems and cultures will collapse under the massive violence imported from the Atlantic world.

But none of that is apparent as the Essex approaches Valparaiso. Captain Porter, thirty-three, and Consul Poinsett, thirty-four, have traveled thousands of miles by very different routes to come face to face here. Porter has embarked upon the longest, strangest cruise in naval history; Poinsett is deeply involved in creating a new nation. The self-reliance of these men is impressive and typically American. No other country could have produced (or empowered) people so certain of their ability as individuals to effect change on a massive scale.

Porter is a ruthless buccaneer and Poinsett a romantic idealist, but each considers himself a patriot and an agent of destiny. The Pacific is not a theater of the larger war nor even understood to be an area of American strategic interest, yet these two young men, a navy captain and an ambassador, both operating well beyond the chain of command, will become the godfathers of all subsequent United States imperialism and nation-building.

Next page