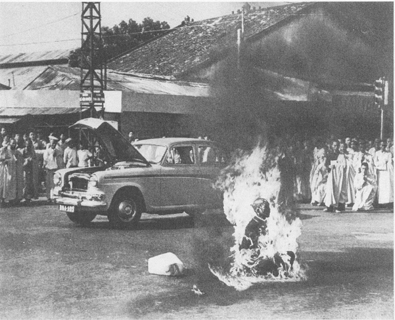

June 1963. To protest South Vietnamese President Diems anti-Buddhist policies, a monk immolates himself in the middle of a busy Saigon street.

Introduction

A few years ago when I began teaching the American literature of the Vietnam War, I tried to find an anthology my students could usea book that collected all the major work in one place. This didnt seem far-fetched; the war had been over for twenty years, and thousands of books had been written about it. But as I searched through libraries and catalogues, new- and used-book shops, I discovered there wasnt one.

Yes, there were anthologies, but most were out of print and none put together all the pieces I considered essential. Some were fitted together like polemics, others relied too heavily on dull reportage. There were solid poetry anthologies, most notably W. D. Ehrharts Carrying the Darkness, but few books had tried to collect everythingthe fiction, the oral histories, the memoirs, the films, the photosand those that did inevitably had gaps. Imagine a comprehensive Vietnam anthology without the work of Michael Herr or Tim OBrien or Larry Heinemann, without a healthy sampling of the oral histories, without a single mention of Platoon, without Ronald Haeberles famous picture of the ditch at My Lai.

Instead of ordering a single volume and sending my students to the campus store, I began digging through the individual novels and poetry collections, poring over the photographic essays, watching the films, taking notes, making photocopies. I haunted the used-book stores for sadly out-of-print work, borrowed books from colleagues, sat in the stacks of libraries. What I finally came up with was a course packet weighing in at around six pounds, the permissions for which were impossible to secure in time for the semester.

While Ive cut a great deal from that original manuscript, this book remains true to its core. I believe Ive chosen and hunted down the elusive permissions for the best and best known works about the war, selections that will give the reader both an essential overview and a deep understanding of how America has seen its time in Vietnam over the past thirty years.

Any Vietnam anthology should bring its reader closer to the war, and in teaching my course I found that one way to accomplish that, beyond presenting students with the usual literature, was to include such powerful and immediate material as photographs, films, and popular songs. They bring the war home inescapably, in the same way they inflamed and informed the public when they first appeared. Its one thing to tell a class that the average age of the combat soldier in Vietnam was nineteen, another to show them a roomful of recruits no older than themselves. By examining the films and songs, my students gained a deeper appreciation for how the war, and its representation, has always been debated in a charged, extremely public forum, and how that debate has changed over the years. As with the literary selections, the photos, songs, and films Ive chosen to include are the best and best known, some, like Haeberles shot of My Lai, practically iconic at this point.

The Vietnam Reader is organized according to two chronological schemes. The first is the typical arc of the Vietnam narrative and traces the tour of duty from induction all the way through returning stateside. The second scheme is the timeframe during which these books and films were released. In certain chapters (such as the popular songs) I found it did more justice to the material to collect works that span a great deal of time but are similar in either theme or genre, thereby illustrating how trends in representing Vietnam echoed the changes in American popular and political culture. This combination of approaches is intended to give the reader a better sense of how both the soldiers and the publics attitudes toward Vietnam have changed as the years pass.

An important point to keep in mind is that this anthology isnt concerned with the Vietnamese or French points of view, which have produced an equal if not greater number of insightful and important works. Instead, this volume is restricted to American views of the war. One remarkable aspect of Americas involvement is that its literature focuses almost solely on the wars effect on the American soldier and American culture at large. In work after work, Vietnam and the Vietnamese are merely a backdrop for the drama of America confronting itself. To balance American views with others herein retrospectwould be to rewrite history and to present a false portrait of Americas true concerns.

A number of themes run through these works or can be read into them, the most obvious the representation of the American soldier, since he (most decidedly he) is usually the main character. In Vietnam literature, even more so than in the literature of previous American wars, the hero is the combat infantryman, whether hes regular Army, Special Forces, or a Marine; there are few pieces concerned with Navy or Air Force personnel, and only a smattering deal with support troops. The soldier and later the vet are often given to the reader as types, if not stereotypes already familiar to the casual reader or viewer. Heres a brief list: professional warrior, reluctant draftee, terrified new guy, hardened grunt, psycho killer/psycho vet, deluded lifer, bumbling ROTC lieutenant, disabled protest vet, troubled/addicted vet. Of course these end up being reductive if not outright slanderous clichs, but the reader will recognize variations on all these characters throughout this book and should be aware of them, and also of who on that list is eligible to play the American hero, and why.

Another major concern in these works is their view of the American presence in Vietnamthat is, the question that tortured all of America back then and still troubles some now: Was the war right or wrong? And was the American presence simply an extension of the American character, and not an anomaly? That is, can (should) the war be related to the larger cultural forces that produced it? Most of these works comment overtly on these questions, though some operate more subtly. Every author (filmmaker, photographer, songwriter) has his or her view of the war, and its rare when that view doesnt surface in the work. The stances of somesay, Ron Kovic in