You may humbug the town as a tragedian, but comedy is a serious business.

S ETUP L INES

Introduction

Theres a lot to be said for making people laugh. Did you know thats all some people have? It isnt much, but its better than nothing in this cockeyed caravan.

J OEL M C C REA , in Preston Sturgess Sullivans Travels

N OBODY REALLY REMEMBERS the 1950s, where much of our story is set, with any accuracy. Great sport is still made of the fifties. Theyre satirized and exploited and even waxed nostalgic about, yet nobody gets them quite right; a sharper close-up of that much-maligned decade is long overdue. The 1950s might have been innocent but they were far from innocuous. Maybe you had to be there. Yet even people who were there accept the standard snapshot. The fifties were largely a victim of bad timingovershadowed by the heroic forties and the histrionic sixties.

Viewed through the lens of its satirical comedians, the fifties were at least as vital and vivid as any flashier decadeand a whole lot funnier. The historians may have been nodding off, but the audiences who flocked to see the new comedians of that time were wide awake. The comedians of the fifties and sixties were a totally different species from any that came before or after, comics whose humor did more than pry guffaws out of audiences. This new postKorean War comedy poked and prodded and observed, demolishing fond shibboleths left and right; it didnt just pulverize us with a volley of joke-book gags.

Teenagers who grew up watching TV in the early fifties were baffled and bored by the comedians their parents doted on, reverentially trotted out each Sunday night by Ed Sullivan, whose show was almost a wing of the Catskills hotels. Many of them enjoyed a last hurrah on The Colgate Comedy Hour, where aging troupers like Eddie Cantor, Jimmy Durante, and Abbott & Costello, refugees from radio, and even vaudeville, grabbed the spotlight week after week. They were consummate entertainers, but they had little to say about the emerging world. Satire then was itself a semiheretical notion, practiced almost exclusively by elite easternersreaders of The New Yorker, regulars at swank little Manhattan botes, and radical Jewish intellectuals.

Books and documentaries about the 1950s blithely skip over the trenchant satire of the period. In 1971 the Village Voice hooted, A look back at the 1950s is enough to make ones flesh creep; what a dismal decade of cultural rubbish. Arthur Penn, the director, claimed in a TV documentary, It was an era that was conspicuous for its dullnessand, as if to illuminate that innate dullness, we get stock shots of Dwight D. Eisenhower, Hula-Hoops, and beach-party movies. But as Norman Podhoretz argued, The Silent Generation was a term invented by the Leftists of the 60s. Ben Stein wrote in Brills Content in a department called Media Myths: Journalists have a lazy habit of dismissing the 1950s as a time when life was sterile, stuffy, and dull. They must have seen too many movies. The only problem with this presumption is that it is wildly, comically wrong. The 1950s were an explosive decade, especially culturally.

David Halberstams not-quite-definitive work, The Fifties, mentions Mort Sahl only in passing in a couple of quips about Eisenhower and Werner von Braun, but no mention of Sid Caesar, Lenny Bruce, Nichols & May, Stan Freberg, Shelley Berman, Tom Lehrer, the Second City, or the new cutting-edge comedy they embodied. There are long sections devoted to Elvis Presley, the TV quiz-show scandals, and the Sullivan show, but nothing about the satirical revolution that was as significant as the rock-and-roll revolt that takes up a chunk of Halberstams tome. In another book about the decade, also titled The Fifties, the authors write (after a polite nod to Caesar and Bruce), In retrospect it was essentially a humorless decade, the prevailing clich that still shrouds the period. It was more an era of fear than fun. Oh, yeah? Tell it to the fans of Sahl, Caesar, Lehrer, Berman, Phyllis Diller, Freberg, Nichols & May, and Steve Allen. Listen to the albums by Allen, Bruce, Sahl, Dick Gregory, and Nichols & May, and youll know all you need to know about American life in the years 1953 through 1965.

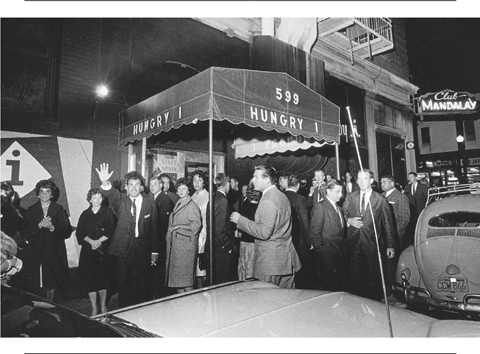

The 1950s, far from fast asleep, helped light the way for many of the cultural eruptions that followed. The sixties had sex, drugs, rock and roll, and civil unrest, but it seems almost culturally drab compared to the fifties artistic turmoil. Consider the following cultural rebels, with and without causes, who either began or flourished then: Charles Schulz, Elvis Presley, Allen Ginsberg, Jack Kerouac, Dave Brubeck, Miles Davis, Charlie Parker, Marlon Brando, James Dean, J. D. Salinger, Harvey Kurtzman, Paul Krassner, Rod Serling, Paddy Chayefsky, William F. Buckley, Jr., Eric Hoffer, Walt Kelly, Vance Packard, Mickey Spillane, Arthur Miller, William Inge, Tennessee Williams, Truman Capote, Norman Mailer, Jules Feiffer, Hugh Hefner, Pauline Kael, Pete Seeger, I. F. Stone, and Marilyn Monroe. Snoring fifties? There was plenty going on once you take a minute to look around. Rosa Parks boarded a bus, Sputnik shot into orbit, Volkswagens rolled off the assembly line, Ray Kroc reinvented the hamburgerand Mort Sahl told a joke about Joe McCarthy. It looks as if the only people snoozing in the 1950s were the historians.

Nearly every major comedian who broke through in the 1950s and early 1960s was a cultural harbinger: Sahl, of a new political cynicism; Lenny Bruce, of the sexual, pharmaceutical, and linguistic revolution (and the anything-goes nature of comedy itself); Dick Gregory, of racial unrest; Bill Cosby and Godfrey Cambridge, of racial harmony; Phyllis Diller, of housewifely complaint; Mike Nichols & Elaine May and Woody Allen, of self-analytical angst and a rearrangement of male-female relations; Stan Freberg and Bob Newhart, of the encroaching, pervasive manipulation by the advertising and public relations culture; Mel Brooks, of the Yiddishization of American comedy; Sid Caesar, of a new awareness of the satirical possibilities of TV; Joan Rivers, of the obsessive catty craving for celebrity gossip and of a latent bitchy gay sensibility; Tom Lehrer, of the inane, hypocritical (and, in Jean Shepherds case, melancholy) nature of hallowed Americana and nostalgia, and in the instances of Allan Sherman and the Smothers Brothers, of its overly revered folk songs and folklore; Steve Allen, of the late-night talk show as a force in comedy and of the reliance on wit over verbal pratfalls; Shelley Berman, of a generation of obsessively self-confessional humor; Jonathan Winters, of the possibilities of free-form improvisational comedy and of a sardonically updated view of midwestern archetypes; and Ernie Kovacs, of surreal visual effects and the unbounded vistas of video.