CONTENTS

TO

HER

WHO CHRISTENED THE SHIP

AND

HAD THE COURAGE TO REMAIN BEHIND

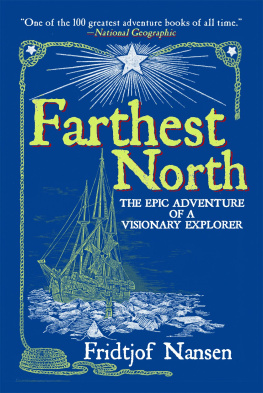

F ARTHEST N ORTH

Dr. Fridtjof Nansen

FRIDTOJF NANSEN

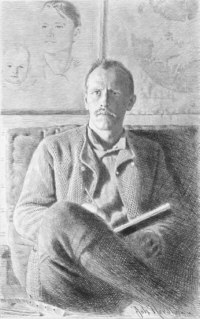

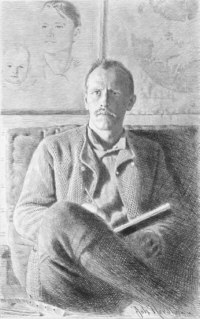

Fridtjof Nansen, Arctic explorer, scientist, diplomat, and humanitarian, was born in Fren, Norway, on October 10, 1861. His father was a well-to-do lawyer; his mother was a vigorous, aristocratic woman who scandalized polite society by taking up skiing. Nansens yearning for outdoor adventure dated from his early childhood. He learned to ski at the age of two; later, the hardy, self-reliant boy delighted in exploring the forests and mountains surrounding the familys home near Oslo. After studying zoology at the University of Christiania (now Oslo), Nansen, then twenty, set sail on the Viking, a sealing ship bound for the waters off Greenland. He later published his recollections of the formative four-month voyage in Hunting and Adventure in the Arctic (1925). From 1882 to 1888 he served as curator of zoology at the Museum of Natural History in Bergen.

In 1888 Nansen led a six-man team that became the first expedition ever to cross the Greenland ice cap. The First Crossing of Greenland (1890) recounts his celebrated trek by ski and sleigh across a desert of ice and snow. His account of a perilous traverse of the unknown ice cap is still one of the most absorbing narratives of adventure, said TheNew York Times. Eskimo Life (1893), a second book about the trip, is a lively and entertaining anthropological study describing the winter he spent at the native settlement of Godthaab on the west coast of Greenland. Upon returning to Norway, Nansen was appointed curator of the zoological collection at the University of Oslo, but immediately began making plans for a journey to the North Pole.

Nansen and his carefully selected crew sailed for the New Siberian Islands on June 24, 1893, aboard the Fram, whose crush-proof triple hull would allow the ship to be frozen in sheets of Arctic ice and then be carried by ocean currents to the North Pole. When it became apparent that the vessel would pass to the south of its target, Nansen attempted to reach the pole by kayak and dog sled. On April 7, 1895, he arrived with colleague Frederik Hjalmar Johansen at latitude 8614N, farther north than anyone had ever been. Farthest North (1897) is his compelling account of the three-year voyage. To hear the story from Nansens lips was to realize that they were truly of the Viking breed, said The New York Times. He later published the scientific results of the journey in The Norwegian North Polar Expedition18931896 (19001906) and chronicled the entire history of Arctic exploration in In Northern Mists (1911).

Afterward, Nansen became increasingly captivated with the emerging science of oceanography. In 1900 he participated in the maiden voyage of the Michael Sars, a ship especially outfitted by the Norwegian government for sea exploration. Nansen went on to develop research methods that had a fundamental influence on the study of oceanography. He chronicled the findings of his many oceanographic excursions in such pioneering works as The Oceanography of the NorthPolar Basin (1902), Northern Waters (1906), and The Norwegian Sea (1909).

Eventually Nansens international prominence drew him into public service as a statesman and humanitarian. In 1905 he was caught up in the events leading to the dissolution of Norways union with Sweden and subsequently became the first Norwegian minister to Britain. Following World War I he headed his countrys delegation to the League of Nations and oversaw the repatriation of war prisoners. In addition, he supervised relief programs to famine-stricken Russia and was instrumental in creating the Nansen passport, a special identification card for refugees. In 1922 Nansen was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize for his humanitarian efforts. The Nansen International Office for Refugees in Geneva, which was founded in 1931 to continue his work, was also awarded the same prize. His several books dealing with affairs of state include Norway and the Union with Sweden (1905), Russiaand Peace (1923), Armenia and the Near East (1928), and Through the Caucasus to the Volga (1931).

The spirit of adventure and exploration flourished in Nansen until the end of his life. In addition to publishing Sporting Days in Wild Norway (1925) and Adventure and Other Papers (1927), he became interested in traveling to the Arctic by airship in order to study meteorological conditions. While visiting America in 1929 he delivered the lecture Why the Arctic Calls Me Again. Fridtjof Nansen died suddenly of a heart attack on May 13, 1930. One of the best friends of mankind and one of the most fearless, generous and chivalrous of men passed away at Oslo yesterday, wrote The New York Times. All explorers will feel sorry at the death of Fridtjof Nansen, radioed Rear Admiral Richard E. Byrd from halfway around the world. He was the dean of explorers and one of the most romantic figures in history.

Nansen was one of the surprising figures who emerged from northern mists and helped to mould the age, wrote his most recent biographer, Roland Huntford. He was the father of modern polar exploration.... He became the incarnation of the explorer as hero. He had the power of inspiring men to act. He opened what is called the heroic age of polar exploration. His successors tried to build themselves in his image. The combatants in the race for the South Pole, Amundsen, Shackleton and Scott, were all his acolytes.... With his wide attainments, he approached the Renaissance ideal of the universal man.

INTRODUCTION TO THE MODERN LIBRARY EXPLORATION SERIES

Jon Krakauer

Why should we be interested in the jottings of explorers and adventurers? This question was first posed to me twenty-four years ago by a skeptical dean of Hampshire College upon receipt of my proposal for a senior thesis with the dubious title, Tombstones and the Mooses Tooth: Two Expeditions and Some Meandering Thoughts on Climbing Mountains. I couldnt really blame the guardians of the schools academic standards for thinking I was trying to bamboozle them, but in fact I wasnt. Hoping to convince Dean Turlington of my scholarly intent, I brandished an excerpt from The Adventurer, by Paul Zweig:

The oldest, most widespread stories in the world are adventure stories, about human heroes who venture into the myth-countries at the risk of their lives, and bring back tales of the world beyond men.... It could be argued... that the narrative art itself arose from the need to tell an adventure; that man risking his life in perilous encounters constitutes the original definition of what is worth talking about.

Zweigs eloquence carried the day, bumping me one step closer to a diploma. His words also do much to explain the profusion of titles about harrowing outdoor pursuits in bookstores these days. But even as the literature of adventure has lately enjoyed something of a popular revival, several classics of the genre have inexplicably remained out of print. The new Modern Library Exploration series is intended to rectify some of these oversights.

Next page