Nansen

Explorer and Humanitarian

Marit Fosse and John Fox

Hamilton Books

An Imprint of

Rowman & Littlefield

Lanham Boulder New York Toronto Plymouth, UK

Copyright 2016 by Hamilton Books

4501 Forbes Boulevard, Suite 200, Lanham, Maryland 20706

Hamilton Books Acquisitions Department (301) 459-3366

Unit A, Whitacre Mews, 26-34 Stannary Street,

London SE11 4AB, United Kingdom

All rights reserved

Printed in the United States of America

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Information Available

Library of Congress Control Number: 2015932743

ISBN: 978-0-7618-6578-0 (pbk : alk. paper)ISBN: 978-0-7618-6579-7 (electronic)

All illustrations courtesy of the Archives of the League of Nations, Geneva.

Front cover: Dr Fridtjof Nansen, High-Commissioner for Refugees, sketched by Alois Derso. [Undated. Archives of the League of Nations, Geneva.] Alois Derso (18881964) and Emery Kelen (18961978) were two internationally recognized caricaturists who worked at the League of Nations for fifteen years. Both were of Hungarian Jewish origin and arrived in Switzerland after the First World War, where they drew humorous caricatures and political satires of the League of Nations delegates and politicians, as well as significant events such as the Disarmament Conference. Their work was published widely in the European press. Derso and Kelen departed Europe on 13 December 1938 aided by friends who recognized the impending dangers facing them due by both being Jewish and their past outspoken criticism of Hitlers rise to power.

TM The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

TM The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

Foreword

Antnio Guterres,

United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees

Fridtjof Nansen was a pioneer in many waysa scientist, an intrepid polar explorer, a respected diplomat. He was also the first High Commissioner for Refugees appointed by the League of Nations. In that role, he profoundly shaped the evolution of international efforts to protect some of the worlds most vulnerable peoplerefugees who have been forced to flee their countries as a result of persecution and conflict.

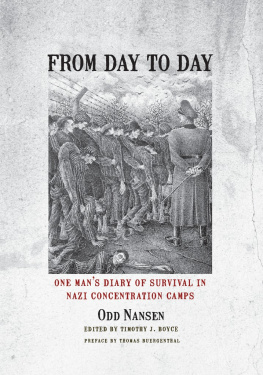

Refugees have lost everythingtheir homes, their communities, their livelihoods, often even their loved ones. No longer under the protection of their own government, they depend on the generosity of other countries to provide them sanctuary and allow them to restart their lives without fear. As refugees, they enjoy a special legal status entitling them to international protection by their host countries. Fridtjof Nansen laid the groundwork for this system, spearheading early legal agreements that later became the basis for the 1951 Refugee Convention and UNHCRs work.

More than ninety years after Nansen was first appointed to assist Russian refugees in Europe, people continue to be uprooted from their homes every day. There are now more than 45 million people worldwide who fled violence and conflict, including over 15 million refugees and 29 million internally displaced persons. If they were a nation, they would make up one of the worlds thirty biggest countries.

Nansen not only pioneered international work on behalf of refugees, he also embodiedalready nearly a century agomany of the fundamental tenets of humanitarian work. His greatest assets were his neutrality and political independence, and the confidence he as an individual inspired in others, irrespective of their national or political background. At a time when the political interests and positions of governments regularly disregarded the suffering of civilians, both Nansens successes and his failures clearly illustrate a fact that still holds true today: humanitarian work is impossible without steadfast fidelity to the principles of neutrality, impartiality and independence. As humanitarian organizations work in crisis settings around the world, our ability to help people in need depends entirely on the credibility we have with all sides in a conflicta credibility that is predicated upon our political neutrality. But at the same time, political independence and neutrality must not be translated to mean paralysis, and Nansen personified the ingenuity and perseverance in finding ways to push through solutions that mark an outstanding humanitarian.

Nansen paved the way for our refugee work, and his legacy remains with us today. In recognition of the importance of his efforts for international refugee protection, UNHCR has since 1954 presented its annual Nansen Refugee Award to individuals and organizations that have made exceptional contributions to the refugee cause. The award boasts a long list of laureates who share Nansens personal conviction. Eleanor Roosevelt, who laboured for decades to champion open-door policies and refugee rights both within the United States and internationally. Graa Machel, the longtime activist who advanced protection norms for refugee children caught in the midst of conflict. Dr Annalena Tonelli, an Italian volunteer who fought against tuberculosis, HIV/AIDS and female genital mutilation among the forcibly displaced in Kenya and Somalia, and who ultimately sacrificed her life for her work. They, like Nansen, are true heroes of refugee protection.

This book is an important one. It portrays the many dimensions of a man who was one of the most interesting personalities of his time. And it shows, through that mans struggles, setbacks and overwhelming victories on behalf of hundreds of thousands of people in need, the fundamental importance of having a strong international system in place for their protection. This system now exists, also thanks to Fridtjof Nansen. But it continues to come under pressure, as respect for human rights runs low in many places, and as racism and xenophobia resurface, time and again, in societies around the world.

As UNHCR continues its work to protect and assist those who need it most, we are reminded each day that whether or not refugees can find safety and restart their lives depends, first and foremost, on the governments, the societies and the communities that take them in. Nansen recognized this, and worked with this knowledge to find creative, often unexpected solutions for refugees and people in need. I hope this book will help to spread this recognition, through the tribute it pays to one of the true humanitarians of all time.

Preface

When we worked together on our previous book about the League of Nations, we realised that much of the work that is currently being carried out by the international organizations is based upon the foundations laid during the 1920s.

Recalling the activities of the League of Nations today is not a fruitless activity given what is taking place on the international scene. For a long time, academic research has neglected this area where ideology and political reality confronted each other. When the League of Nations was dissolved on 18 April 1946, Lord Robert Cecil said: The League is dead. Long live the United Nations. When the United Nations first saw the light of day, it was already clear that the League of Nations, for all its faults, was the ideological laboratory that had modelled, pioneered, even forged, the whole universe of the international world to come.

While the financial turmoil of 2008 was still sending shockwaves through the European countries and across the rest of the world, we realised that much of what we are living through today has similarities to what went on between the two World Wars. According to the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, the number of people in situations of displacement at the time of writing has reached 45 milliona fourteen year high. These figures include 15.4 million internationally displaced refugees, as well as 28.8 million people forced to flee their homes within their own countries. Some ninety years ago, Nansen did not blanch when confronted with what were for the time similarly daunting figures.

TM The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

TM The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.