CAMPAIGN 262

MANZIKERT 1071

The breaking of Byzantium

| DAVID NICOLLE | ILLUSTRATED BY CHRISTA HOOK

Series editor Marcus Cowper |

CONTENTS

ORIGINS OF THE CAMPAIGN

The battle of Manzikert in 1071 is widely regarded as one of the most significant turning points in medieval history. More recently, some historians have downgraded its importance, noting that it was not the defeat of a Byzantine army by a Saljuq Islamic army which opened the Byzantine Empire to Turkish conquest, but the Byzantine civil war that followed that defeat. Meanwhile western historians still tend to present the battle of Manzikert as the culmination of a Turco-Islamic assault upon the Byzantine bulwark of a Christian world struggling for survival against an Islamic threat. The reality was far more complex.

Byzantine civilization had its roots in both the Graeco-Roman and Early Christian pasts. Its people believed themselves to be under divine protection while their leaders were doing Gods work in this world. As a result, their Orthodox Christianity was central to their identity. Referring to themselves as Romaioi or Romans and their state as the New or Second Rome, the Byzantines clear sense of superiority annoyed several of their neighbours. Many foreign peoples who had been forcibly settled within the Empire by earlier Byzantine emperors had, by the 11th century, been Byzantinized. Only on the peripheries did non-Greek-speaking, non-Orthodox Christian peoples predominate numerically. In the east these included Armenians, Syriacs, Kurds, Arabs, Georgians and perhaps Laz.

Meanwhile the Byzantine Empires relations with its western neighbours had a profound impact on the events leading up to the battle of Manzikert, and even more so on the events that followed. Although the Great Schism between the eastern Orthodox and the western Catholic Churches dates from the year 1054, it was as yet merely a theological dispute between senior churchmen. Indeed westerners were widely admired in Byzantium for their simple piety and military prowess, being widely welcomed as military recruits.

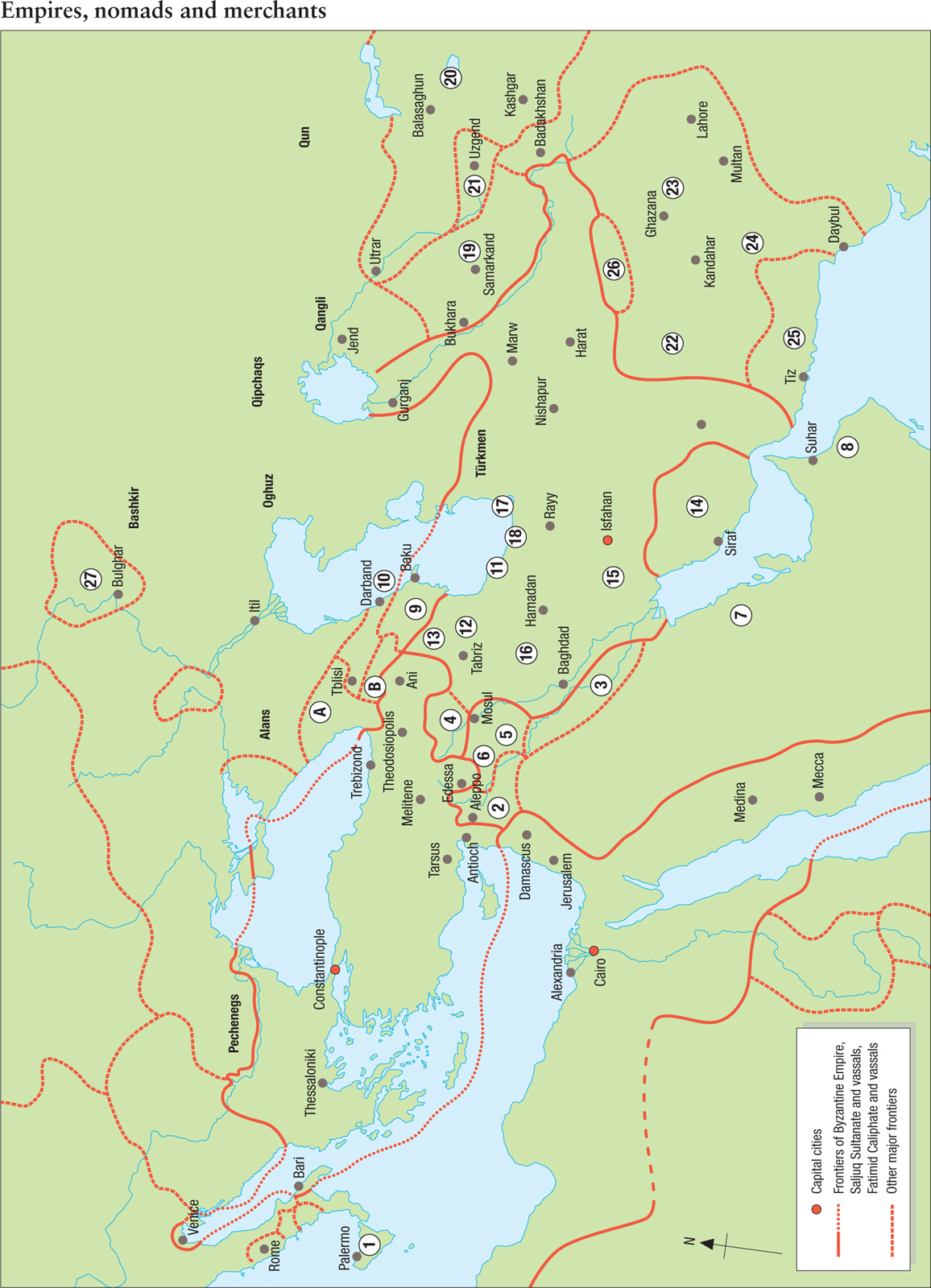

Sicily under local qadis (judges).

Mirdasids.

Mazyadids.

Marwanids, Saljuq vassal since 1056. S

Uqaylids.

Numayrids (probably changed allegiance from Fatimid to Abbasid Caliphate in 1060).

Qarmati (Shia but not recognising Fatimid Caliphate).

Ibadi Imams (Saljuqs apparently controlled the Omani coast after 1054).

Sharwan Shahs.

Hashimids.

Musafirids (Shia but vassals of Saljuq Sultanate).

Rawwadids (Saljuq vassals since 1054). S

Shaddadids (Saljuq vassals since reign of Tughril Beg). S

Buwayhids (Shia but not recognising the Fatimid Caliphate).

Annazids. S (probably)

Kakuyids (Saljuq vassals since 1051). S

Bawandids (Shia but recognising Saljuq overlordship). S

Ziyarids (Saljuq vassals probably since c.1041). S

Western Qarakhanids.

Eastern Qarakhanids.

Qarakhanids of Farghana (suzereinty varying between the Eastern and Western Qarakhanids.

Maliks (vassals of Ghaznawids).

Ghaznawids.

Khusdar (vassals of Ghaznawids).

Makran (in revolt against Ghaznawids since 1029).

Ghurids (vassals of Ghaznawids).

Volga Bulgars.

Other Christian states

A Georgia.

B Armenian Lori-Tashir.

S vassal of Saljuqs

Shia or normally supporting the Fatimid Caliphate

vassal of the Byzantine Empire

In the 11th century Christians were a substantial community within the Islamic regions bordering the Byzantine Empire. Today they are a small minority but several medieval monasteries and churches still exist, including the Tahira Church at Qaraqush, near Mosul. (Authors photograph)

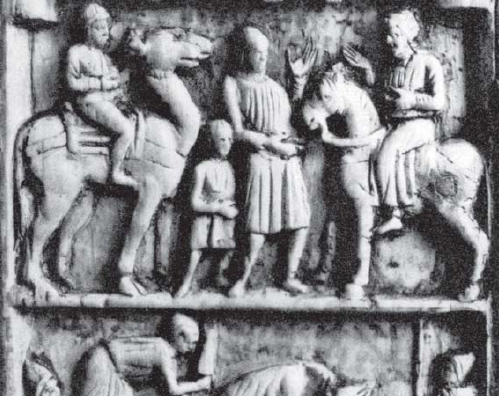

The events surrounding the battle of Manzikert focused upon the eastern part of the Byzantine Empire, in what is now Turkey. Here the Byzantine authorities continued the long-standing Romano-Byzantine policy of forcible population movement as a means of strengthening the Empires defence. Hence, between the 7th and 11th centuries, large numbers of people had been brought in from Europe, the Middle East and the Eurasian Steppes. In other cases unreliable elements had been moved out of Anatolia, for example, to Thrace where there was already a substantial Armenian community.

The carvings on an Armenian church on Aghtamar Island in Lake Van date from a century before the battle of Manzikert, but they shed light on the costume and equipment of this region when it was ruled by independent Armenian kings. (Authors photograph)

In many cases these transfers had a religious motivation, the Imperial government being particularly concerned about perceived heresy in vulnerable frontier regions bordering the Islamic world. On the other hand minor theological differences were usually tolerated, if only because their followers numbered millions. For example, in the 10th and 11th centuries Monophysites who maintained that Jesus Christ had one nature which was both human and divine, included the Armenian and the largely Arabic-speaking Syriac Churches. In contrast the Nestorian Church, which maintained that Jesus Christ had two natures, one human and one divine remained unacceptable. Instead Nestorians found sanctuary under Islamic rule where their doctrines were closer to those of Muslims, who regarded Jesus as a divinely inspired man in other words a prophet.

The wealth of ArabChristian communities in the 11th century Marwanid amirate of Mayyafariqin and Diyarbakr was reflected in the decoration of some churches. This wall mosaic in the Monastery of Mar Gabriel, near Mardin, is a survival from the early medieval period. (Authors photograph)

The persecution of more extreme heresies continued. They included the Paulician sect, which was brutally suppressed by the Byzantine authorities before briefly reappearing in the Eastern Euphrates Valley where the Manzikert campaign would later be fought. At the start of the 11th century a related sect called the Tondrakeci was still recorded, many of its surviving remnants fleeing to Islamic territory where some of its followers, the supposedly sun worshipping Areworik fought for Damascus during the 12th century.

Armenians were, of course, central to the story of the battle of Manzikert. Early medieval Armenian society was not urbanized and the existing towns were Greek foundations, which, after being used as Roman garrison centres, had flourished under early Islamic rule. These and newly established towns had attracted Muslim settlers as well as garrisons, almost all under the control of Arab amirs rather than an Armenian naxarar aristocracy who were themselves vassals of the Abbasid Caliph in Baghdad. Amongst these new centres were Manzikert, Ahlat, Archech [Eri] and Perkri [Muradiye], which would feature in the events around 1071.