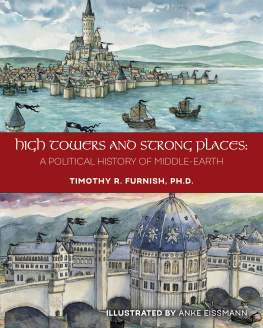

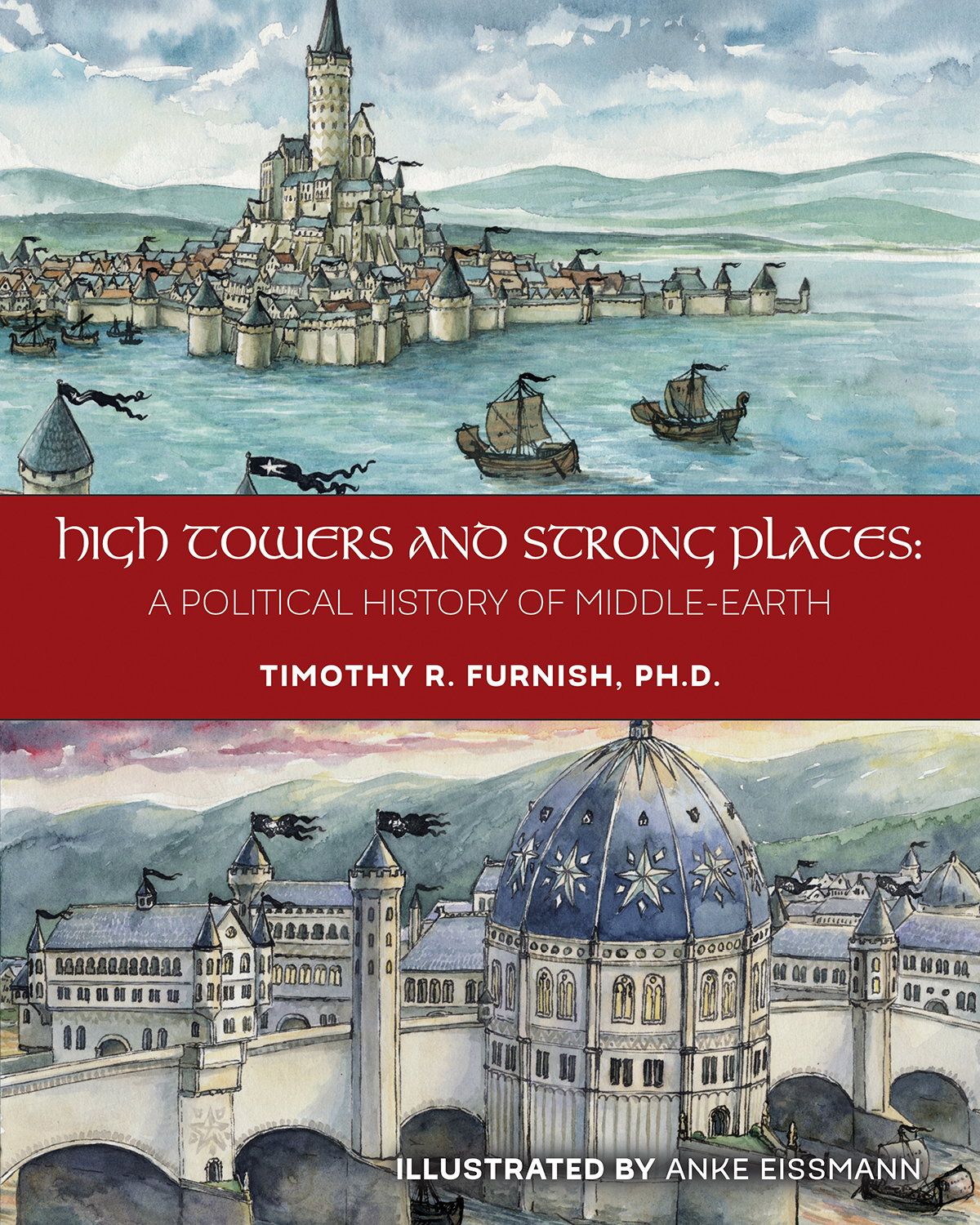

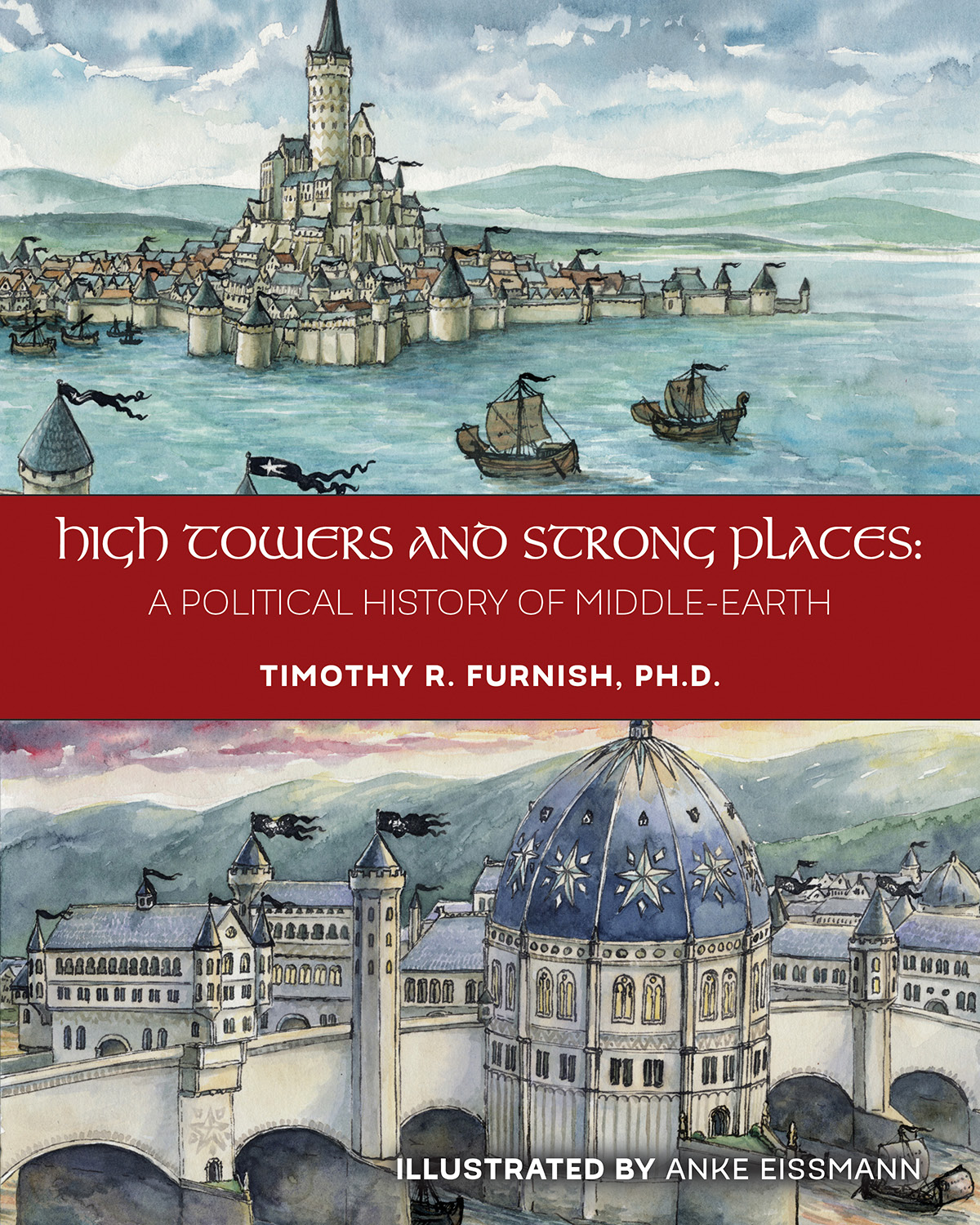

High Towers and Strong Places:

A Political History of Middle-earth

Timothy R. Furnish, Ph.D.

illustrated by anke eissmaNn

High Towers and Strong Places: A Political History of Middle-earth 2016 by Timothy R. Furnish. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever, including Internet usage, without written permission from Oloris Publishing LLC., except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

First Edition

First Printing

ISBN-10: 1-940992-50-8

ISBN-13: 978-1-940992-50-1

Printed in Canada

Cover art & illustrations 2016 by Anke Eissmann

Maps & diagrams 2016 by Aaron Siddall

Author photograph Timothy R. Furnish

For more information please see: www.olorispublishing.com.

Contents

INTRODUCTION

I first read The Hobbit when I was 16, in the fall of 1976. Some forever unknown high school chum inadvertently put a copy of the book in my gym bag, which was backstage during our high school practice for the play M*A*S*H. Hawkeye Pierce almost tossed it as a silly kids bookbut instead, I read the whole thing that very night, then made a trip to the local mall the following weekend, purchased the trilogy and read it in, as I recall, three days. Like many, I choked up when the Balrog pulled Gandalf off the bridge, something that Id never experienced with any previous fiction book. Of course, my senior English composition paper the next year dealt with The Lord of the Rings , and I even used The Silmarillion , which had been published in the fall of 1977. Over the intervening three-and-a-half decades, I have not only added the rest of Tolkiens published works on Middle-earth to my collection as they came outI have re-read the trilogy numerous times, and The Hobbit to my boys once they were old enough to enjoy it (which seems to have stuck, since as I write they are both in the other room playing Shadow of Mordor on Xbox). Ive also lost count of how many times Ive watched Peter Jacksons excellent movies set in Middle-earthyes, the extended editions.

Over the years, Tolkien has seeped into my mind as well as my soul, fusing with my other areas of interest and expertise, both personal and professional: world and Middle Eastern history; eschatology; comparative politics; military topics and weaponry. While I greatly esteem the HobbitsFrodos heroic pathos, Sams stalwart simplicity, Merrys discerning devotion to his friends and especially to King Thoden, Pippins puckish braveryI found myself, with every re-read of LotR , increasingly skipping over the Halfling-centric chapters, even (or rather, especially) those involving Gollumwho, for all his centrality to the story, rather bored me. This will possibly exasperate those who see one of the hobbitseither Sam (as Tolkien himself did) or Frodoas the main hero of the story. But the psychology of addiction or the class differences between Hobbits were not what moved me; nor, despite my own pipe collection, did the relative virtues of Old Toby v. Longbottom Leaf. Rather, I was fascinated by the chapters describing the great battles, or presenting the geopolitical views of the major strategists like Gandalf: The Council of Elrond, Helms Deep, The Palantr, Minas Tirithand of course, most importantly, The Siege of Gondor, The Battle of the Pelennor Fields, and The Last Debate. If fans of Tolkien can be divided into, broadly speaking, those focused on Frodos having worn the One Ring too long (psychology and Hobbits); those who cant get enough about Elves (fairy); and those overjoyed that there is, finally, a King in Gondor (epic battles and politics)I would be classified as amused by the first topic, intrigued by the second, but completely fascinated by the third, choosing to focus on the high and the noble rather than the simple and ordinary, without, of course, denigrating the latter.

While, in a very real sense, every member of the Fellowship in LotR is heroiceven tragic Boromiras, indeed, are many of the other major characters, I think it safe to say that most Tolkien fans and critics would agree that there are four major heroes: Sam, Frodo, Gandalf, and Aragorn. The first two exemplify simple hobbit heroism, while the latter two embody grand strategy, geopolitics and, if you will, high heroism. In fact, as Tolkien himself says Gandalfs opposite was, strictly, Sauron, on one part of Saurons operations; as Aragorn was in another In terms of power, piety and guidance, Gandalf was the closest Good analog to Sauron; Aragorn, on the other hand, was the Dark Lords positive opposite as the legitimate ruler of most of Middle-earth and the instituter of the Dominion of Men.

I also read Tolkiens other works much the same waypassing over character development and psychological tensions in favor of grand strategy and military tactics. Parallel to this fascination with the military history of Gondor and Gondolin and Nmenor, I found myself falling into the habit of looking at surrounding landscapes and inserting them into Middle-earthor, perhaps more accurately, finding Tolkieneque counterparts in our own world: rows of hedges might conceal Black Riders just on the other side; concrete ruins projecting from north Georgias Lake Lanier resemble relics from a different age, possibly left over from Gondors zenith of empire; unidentified woodsmoke rising above a tree line could mark a Ranger encampment.

Seeing Middle-earth around every turn in the road only became easier after Jacksons movies were released; and my interest in Middle-earth warfare exploded after I taught several Masters-level classes in military historya field which was new to me professionally, if not personally. Now, gazing out my study window on the north Georgia countryside, I no longer just see Barrow-downs when the ridge line is foggyI wonder how many Men (or Elves or Dwarves, or combination thereof) would be needed to hold that high ground against an Orc onslaught. Casting a wider historical net, in recent years I began to speculate about military modes of Middle-earth across space and time: Were the Third Age Wainriders who invaded Gondor 1200 years before the War of the Ring heavy or light cavalry? How realistic were the Nmenorean steel bows and thangail battle formations of the Second and early Third Ages? Did the struggle Trins band of outlaws waged against Morgoths First Age Orcs in Doriath qualify as guerrilla warfare?

I wanted to read more about the military history of Middle-earth. But not all that much has been written about the topic, and what has been done is neither systematic nor comprehensive. I started looking for such books and articles, and found only a few; notably Chris Smiths book The Lord of the Rings: Weapons and Warfare. An Illustrated Guide to the Battles, Armies and Armor of Middle-earth and Robert Woonam-Savages article The Matriel of Middle-earth: Arms and Armor in Peter Jacksons The Lord of the Rings Motion Picture Trilogy; But these fine works really deal with the movie, and then only with the late Third Age battles depicted thereinnot with the vast scope of kingdoms and their conflicts across space and time as set out in the Tolkien legendarium. And since militaries exist to defend the civilization or polity which created them, its only logical to exploreinsofar as possiblethe political history of Middle-earth as well as, on a more meta-narrative level, whether the history (and thus the warfare) of Tolkiens Secondary World could be analyzed in a Primary World manner. Then, like any good (albeit borderline obsessive-compulsive) historian, I heeded the scholarly adage that good criticism will take note of what other critics have written and began canvassing not just popular, but scholarly works on Tolkien, focusing on ones dealing with the political and military history of Middle-earth.