Copyright 2013 by Lynne Olson

All rights reserved.

Published in the United States by Random House,

an imprint of The Random House Publishing Group,

a division of Random House, Inc., New York.

R ANDOM H OUSE and colophon are registered trademarks of Random House, Inc.

Grateful acknowledgment is made to Houghton Mifflin Harcourt for permission to reprint excerpts from The Wartime Journals of Charles A. Lindbergh by Charles A. Lindbergh, copyright 1970 by Charles A. Lindbergh and renewed 1998 by Anne Morrow Lindbergh and Reeve Lindbergh, and excerpts from War Within and Without: Diaries and Letters of Anne Morrow Lindbergh, 19391944 by Anne Morrow Lindbergh, copyright 1980 by Anne Morrow Lindbergh. Reprinted by permission of Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. All rights reserved.

PHOTO CREDITS: All images are from the Library of Congress with the exception of , which is reprinted courtesy of Century Association Archives Foundation.

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA

Olson, Lynne.

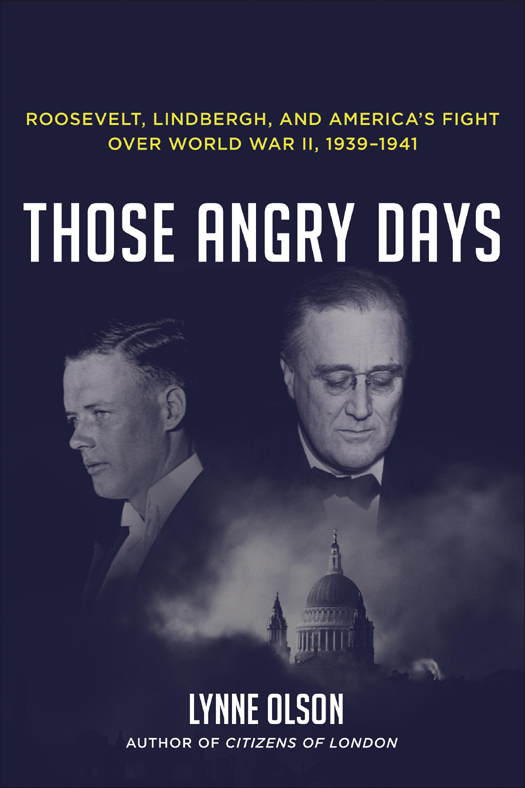

Those angry days: Roosevelt, Lindbergh, and Americas fight over World War II, 19391941 / by Lynne Olson.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references.

eISBN: 978-0-679-60471-6

1. World War, 19391945United States. 2. World War, 19391945Diplomatic history. 3. Roosevelt, Franklin D. (Franklin Delano), 18821945Political and social views. 4. Lindbergh, Charles A. (Charles Augustus), 19021974Political and social views. 5. IsolationismUnited StatesHistory20th century. 6. Intervention (International law)History20th century. 7. United StatesPolitics and government19331945. 8. Political cultureUnited StatesHistory20th century. 9. United StatesForeign relations19331945. 10. United StatesMilitary policy. I. Title.

D753.O47 2013

940.5310973dc23 2012025381

www.atrandom.com

Jacket design: Michael Boland for The Boland Design Company

Jacket images: The New York Public Library/Art Resource, N.Y. (Charles Lindbergh), Bettmann/Corbis (Franklin D. Roosevelt), Herbert Mason/Daily Mail/Getty Images (St. Pauls Cathedral)

v3.1_r1

Though historians have dealt with the policy issues, justice has not been done to the searing personal impact of those angry days.

ARTHUR M. SCHLESINGER JR.

In a democracy, a politician is supposed to keep his ear to the ground. He is also supposed to look after the national welfare and to attempt to educate the people when, in his opinion, they are off base.

JOHN F. KENNEDY

You can always count on Americans to do the right thingafter theyve tried everything else.

WINSTON CHURCHILL

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

O n a soft April morning in 1939, Charles Lindbergh was summoned to the White House to meet President Franklin D. Roosevelt, arguably the only person in America who equaled him in fame. The images of the two men had been indelibly impressed on the nations consciousness for yearsLindbergh, whose solo flight across the Atlantic in 1927 had mesmerized and inspired his countrymen, and Roosevelt, whose energetic, confident leadership had helped jolt a Depression-mired America back to life.

When Lindbergh was ushered into the Oval Office, he found FDR seated behind his desk. It was their first face-to-face encounter, but no one would have guessed that from the presidents warm, familiar manner. Leaning forward to clasp Lindberghs hand, Roosevelt welcomed him as if he were an old friend, asking him about his wife, Anne, who, the president noted, had been a high school classmate of FDRs daughter, Anna.

His head thrown back, with his trademark cigarette holder tilted rakishly upward, Roosevelt exuded charm, joie de vivre, and an unmistakable air of power and command. During his thirty-minute chat with Lindbergh, he gave no sign of the many grave problems weighing on his mind.

He was, in fact, in the midst of one of the greatest crises of his presidency. Europe was on the brink of war. The month before, Adolf Hitler had seized all of Czechoslovakia, violating the promise he had made at the 1938 Munich conference to cease his aggression against other countries. In response, Britain and France had promised to come to the aid of Poland, the next country on Germanys hit list, if it were invaded. Both Western nations, however, were desperately short of arms, a situation that FDR was trying to remedy. But he was faced with a dilemma. Thanks to the provisions of neutrality legislation passed by Congress a few years earlier, Britain and France would be barred from buying U.S. weapons once they declared war on Germany. As Roosevelt knew, his chances of persuading the House and Senate to repeal the arms ban were close to zero.

But he mentioned none of that in his conversation with Lindbergh. Nor, in the course of his genial banter, did he betray any hint of the considerable suspicion and distrust he felt for the younger man sitting opposite him. Five years before, Roosevelt and Lindbergh had engaged in what the writer Gore Vidal called a mano a mano duel, in which the president emerged as the loser. FDR hated to lose, and his memories of the 1934 incident were still raw and bitter.

The clash had been prompted by Roosevelts cancellation of airmail delivery contracts granted by his predecessor, Herbert Hoover, to the nations largest airlines. Charging fraud and bribery in the contract process, Roosevelt directed the U.S. Army Air Corps to start delivering the mail. Lindbergh, who served as an adviser to one of the airlines, publicly criticized FDR for ending the contracts without giving the companies a chance to respond.

Less than seven years after his history-making flight, the thirty-two-year-old Lindbergh was the only person who could match the fifty-two-year-old president in national popularity. They were alike in other ways, too. Both were strong-willed, stubborn men who believed deeply in their own superiority and had a sense of being endowed with a special purpose. They were determined to do things their own way, were slow to acknowledge mistakes, and did not take well to criticism. Self-absorbed and emotionally detached, they insisted on being in control at all times. A friend and distant relative of FDRs once described him as having a loveless quality, as if he were incapable of emotion. Of Lindbergh, a biographer wrote: The people he called friend were mainly, to him, good, functional, temporary acquaintances. He seemed to have taken much more than he gave in the way of warmth and affection.

The conflict between the president and Lindbergh quickly became front-page news. A former airmail pilot himself, Lindbergh warned that Air Corps fliers had neither the experience nor the right type of instruments in their planes to take on the extremely hazardous job of delivering the mail, which often involved night flying in blizzards, heavy rain, and other extreme weather. To the administrations embarrassment, his assessment proved correct. In the four months that Army pilots flew the mail, there were sixty-six crashes, twelve deaths, and, as one writer put it, untold humiliation for the Air Corps and White House. On June 1, 1934, following rushed negotiations between the government and airlines to come up with new delivery agreements, the commercial companies resumed mail delivery.