ALSO BY ALBERT MARRIN

Thomas Paine: Crusader for Liberty

A Volcano Beneath the Snow: John Browns War Against Slavery

Black Gold: The Story of Oil in Our Lives

Flesh and Blood So Cheap: The Triangle Fire and Its Legacy

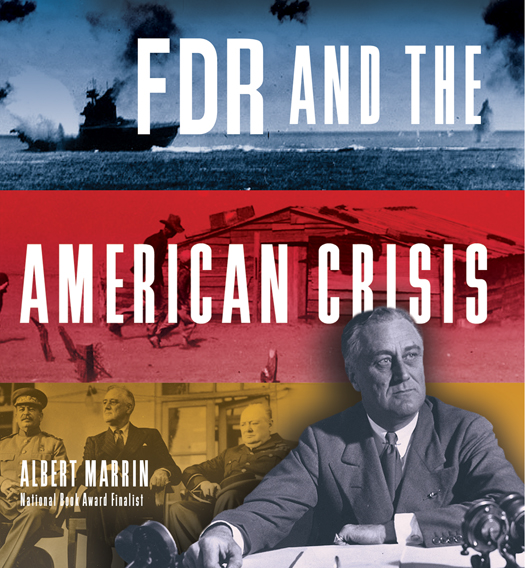

THIS IS A BORZOI BOOK PUBLISHED BY ALFRED A. KNOPF

Text copyright 2014 by Albert Marrin

Jacket photographs copyright 2014 courtesy of U.S. National Archives (top) and the Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library and Museum (all others)

All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Alfred A. Knopf, an imprint of Random House Childrens Books, a division of Random House LLC, a Penguin Random House Company, New York.

Knopf, Borzoi Books, and the colophon are registered trademarks of Random House LLC.

For image credits, please see .

Visit us on the Web! randomhouseteens.com

Educators and librarians, for a variety of teaching tools, visit us at RHTeachersLibrarians.com

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Marrin, Albert.

FDR and the American crisis / Albert Marrin.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-385-75359-3 (trade) ISBN 978-0-385-75360-9 (lib. bdg.) ISBN 978-0-385-75361-6 (ebook)

1. Roosevelt, Franklin D. (Franklin Delano), 18821945Juvenile literature. 2. PresidentsUnited StatesBiographyJuvenile literature. 3. World War, 19391945United StatesJuvenile literature. 4. United StatesPolitics and government19331945Juvenile literature. I. Title.

E807.M29 2015

973.917092dc23

[B]

2013042351

Random House Childrens Books supports the First Amendment and celebrates the right to read.

v3.1

History, by apprizing [people] of the past, will enable them to judge of the future; it will avail them of the experience of other times and other nations; it will qualify them as judges of the actions and designs of men.

THOMAS JEFFERSON, Notes on the State of Virginia (1785)

In the darkness with a great bundle of grief the people march.

In the night, and overhead a shovel of stars for keeps, the people march:

Where to? what next?

Carl Sandburg, The People, Yes (1936)

Washington, D.C., March 4, 1933. Inauguration Day. A dull, damp, dismal winter day with thick gray clouds gliding overhead.

Half a million people, standing ten deep in places, lined Pennsylvania Avenue, the capitals main thoroughfare stretching from the White House to Capitol Hill. To gain a better view, some stood on stepladders and soapboxes; a few brave souls climbed into trees, clinging to leafless branches. One hundred thousand others waited on the lawn in front of the U.S. Capitol, their feet squishing in the sodden earth.

Despite the festive decorations, the crowd was as gloomy as the weather. America was losing faith in itself. Now is the winter of our discontent the chilliest, an onlooker wrote. Fear, bordering on panic, loss of faith in everything, our fellowman, our institutions, private and government. Worst of all, no faith in ourselves, or the future.

Now in the fourth year of the Great Depression, America was suffering the worst The guns had shields that resembled cages at a distance.

A

New Yorker cover depicting President Hoover and FDR on their way to the inauguration. (March 4, 1933)

Meanwhile, a gleaming limousine of the blackest black pulled up to the front door of the White House. A big man in a fur-trimmed coat, striped suit, and tall silk hat sat in the backseat. From the expression on his face, Franklin D. Roosevelt seemed anything but frightened. Born into one of Americas oldest familiesa man with great personal charm and a presence that drew others to himhe radiated self-confidence.

FDR, as everyone called him, had always believed in his destiny. When he was five years old, his parents brought him to the White House to meet President

Roosevelt ignored the advice. He thought the presidency the greatest prize this side of paradise. Wouldnt you be President if you could? he once asked a guest. Wouldnt anybody?

Now president-elect, he waited in the limousine. Moments after it arrived, a butler opened the door, and Herbert Hoover, the outgoing president, took a seat beside him.

Upon arriving at the Capitol, the limousine stopped under the main stairway leading to the Rotunda, hidden from the crowds view. Only family members, trusted aides, and his Secret Service detail ever saw Roosevelt get into or out of a car. A victim of polio, he dragged along his withered legs. No president had faced such a physical challenge when he took office. Fearing the public would lose confidence in his leadership, FDR treated his disability as a secret, hiding its full extent from the American people.

Two husky Secret Service men lifted him out of the vehicle. Carefully, they placed him in a wheelchair, of Roosevelts own design, and rolled him into the Capitol along a ramp built for the inauguration. Once inside, they lifted him out of the wheelchair and stood him up, locking the steel leg braces he wore under his trousers. Each brace weighed ten pounds and extended from his waist to his heel. Holding a cane in one hand, he leaned heavily on the arm of his eldest son, James, with the other. After steadying himself, he swung his legs from the hips and walked the thirty-five feet to the platform on the East Portico.