To my son, Lee Jin.

A golden benefit you really are.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

For providing me with the finest instruction and patience, I must thank Chan master Hsuan Hua, tai chi chuan master Tung-tsai Liang, Zen master Dainan Katagiri, dharma master Chen Yi, and master healer Oei Kong-wei.

Special thanks to Patrick Gross for all his early editing and formatting of the text, and to Richard Peterson for the incredible cover photo collage and the photos that illustrate each exercise.

Peoples natures are basically the same;

it is their practices which set them far apart.

Confucius

| INTRODUCTION |

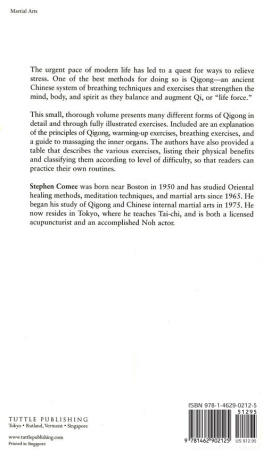

T he purpose and hope for this work, beyond the sharing of these marvelous ancient Taoist teachings with the public, is that its contents will help clarify and add a proper depth of meaning to the many oversimplified explanations given in so many of the popular Taoist and qigong books available in English today. I hope that it will also make clear the many overly mystified explanations that predominate in these popular writings as well.

The Taoist Canon (Tao tsang) consists of some 1,600-plus volumes, of which 75 percent deal primarily with the so-called arts of nourishing life (yang sheng shu), of which qigong is a part. It would be unreasonable to assume that any one book could possibly elucidate completely the teachings of Taoism; this work represents but a small fraction of the ancient wisdom. But what this book does do, if I have been successful, is provide a useful explanation of Taoist restorative and healing arts and comprehensive instructions on the most effective series of qigong longevity exercises developed by the Taoists, called the Eight Brocades and the Lesser Heavenly Circuit.

What makes this work unique, however, is not just its instructions on these Taoist practices but its commentaries on the exercises by the highly respected master Li Ching-yun. Li Ching-yun is one of the most famous Taoist masters of this century. He reportedly practiced these exercises for more than one hundred years, and historical documents show that he was 256 years old at the time of his death in the early 1930s. His explanations, endorsements, and longevity attest to and validate the Eight Brocades as the culmination of Taoist health and qigong practices.

Although this book deals primarily with Taoist practices, it reveals so much more about Taoism in general than could ever be learned from just studying Taoist historical and philosophical works. Practice and philosophy go hand in hand, being just two sides of the same coin. Whether you choose to practice any of the exercises in this book, your understanding of Taoism will be greatly increased by just reading it.

The book has been organized to accommodate both the advanced and the beginning student. The text relies upon several works that I have translated from the Chinese as well as upon my own practice of qigong. The primary translation comes from a stone rubbing of the original Eight Brocades text by Kao Lin of the early Ching dynasty (circa seventeenth century A.D.). (Note: The Eight Brocades text was reproduced for the stone rubbing; the date that it was first drafted is unknown.) Also included are extensive translated passages from General Yang Shens biography of the immortal Li Ching-yun, published in Wan Hsien, China, in 1936. Where I deemed them informative, I have translated small passages from other works as well, but it is not necessary to list them all here.

Basically the reader will encounter three separate voices in the material: that of the Kao Lin text, that of Li Ching-yun, and of course, my own voice, usually designated Authors Comments. The translated voices were originally presented in separate sections, with my comments included as footnotes, but that arrangement resulted in a lot of repetition. Ultimately, I found it simpler for readers to follow the material if everything was contained in one running text.

The book provides a background explanation of the Eight Brocades, the how-to aspects of the form, and supplementary techniques to further develop your practice. To learn the exercises, it is important to read the entire book first, then begin performing the exercises according to the instructions provided.

Whether you are just starting out in learning about Taoism or are already engaged in Taoist practices, you will find many new and wonderful insights in the contents of this work, as many portions are appearing in English for the first time.

| TAOIST LONGEVITY PRACTICES |

T hroughout history, Taoists have propagated the development and restoration of the human body, breath, and spirit. They call these the Three Treasures (san pao): ching, qi, and shen, corresponding in simplest terms to body, breath, and spirit. The human body results from the culmination of sexual forces, or ching, is animated by the vital force of qi, and made conscious through the activation of shen. By preserving the Three Treasures, Taoists believe that people can achieve optimal health and longevity and also create within themselves the alchemical gate to immortality.

The Arts of Nourishing Life

Three practices dominate the Taoist quest for health, longevity, and immortality. The first is the ingestion of herbal medicines (fu erh) and the purification dietary regimes. The second is the performance of physical and respiratory exercises (tu na) to gain breath control and mobilize the qi. The third practice is the achievement of mental and physical tranquility through meditation (ching tso). If one or more of these three practices can be maintained in your daily life, you will at the very least restore your vitality and stamina (having youthfulness in old age). Depending on the depth and sincerity of your efforts, you could attain longevity (living to over one hundred years of age in good health) or actually discover the elixir of immortality.

Many Taoists consider longevity (shou) to mean the ability to experience youthfulness in old age and to live in good health to the end of ones days. Sickness prevents practitioners from putting all their effort toward immortality, and death ensures failure. The notion of living beyond one hundred years of age has always been considered a milepost of sorts, proving to everyone that your art and teaching have merit.

The term corresponding to immortality (hsien) literally means man in the mountains. The idea is of a hermit seeking complete absorption into nature. Many schools of Taoism, however, do believe and propagate the idea of actual physical immortality. The most widely accepted meaning contends that when the practitioner dies, the mental and spiritual energies remain intact after death; in other words, the practitioner remains completely conscious during the death experience. In Taoist terms, the heavenly spirit (hun) remains, while the earthly spirit (po) is shed.

In order to preserve the Three Treasures and forge the elixir of immortality, Taoists developed physical and respiratory exercises that originally were placed under the general heading of arts of nourishing life. The entire basis for what is now popularly called qigong began with the simple experiment of healing with the breath, which in turn led to the discovery of qi energy itself.

Next page