Table of Contents

To those on all sides who lost

their lives on November 11, 1918

Now, God be thanked, Who has matched us with His hour,

And caught our youth, and wakened us from sleeping.

RUPERT BROOKE, 1914

What passing-bells for these who die as cattle?

Only the monstrous anger of the guns.

WILFRED OWEN, 1917

PRAISE FOR Eleventh Month, Eleventh Day, Eleventh Hour

Beautifully written... Persicos story dramatically juxtaposes the patriotic fervor of both sides with the soldiers awakening to the blood and mud of the front lines.

Deseret News

Exhaustive research... [Persico puts] a human face on a horrific war... [and] bring[s] the war back to us in all its visceral horror.

Minneapolis Star Tribune

Persico has a flair for describing the hostilities in striking terms.... [He] seems incapable of writing an uninteresting paragraph.

The Orlando Sentinel

With admirable skill, Persico weaves in every facet of World War I: how it began, life in the trenches and the plague of rats.... He illuminates key battles in which the men fought, and he recounts their first days in the trenches as well as other moving moments.

USA Today

An ambitious book that looks at the unnecessarily deadly end of World War I and resembles Aleksandr Solzhenitsyns Gulag Archipelago in its crushing, relentless chronicle of horrors.

San Jose Mercury News

A compelling look at the final hours of this bloody conflict... The remarkable stories of sacrifice and courage go a long way toward illuminating a war that was supposed to end all wars.

Entertainment Weekly

Joseph Persicos new book eloquently examines... paradoxes about the Great War and war in general.... Research and readability are constants in this book.... One of Persicos best.

The Sunday Gazette (Schenectady, New York)

Veteran non-fiction author Joseph Persico has found a fresh way to tell the story of World War I that makes it seem like it occurred yesterday, not 86 years ago.... I could not stop reading, not even for sleep.... Persicos book demonstrates starkly... how the traditional definition of bravery on the battlefield equated to stupidityand fatal stupidity at that.

Milwaukee Journal Sentinel

Persico has a well-deserved reputation for a solid writing style. His latest effort combines graphic casualty counts with individual stories of common people, and famous personages, to complement his analysis.... Persicos work is a welcome addition to the field and adds to our general background knowledge of the first global conflict.

The Philadelphia Inquirer

Superb... Persico creates more than a historical account of events or an examination of high strategy. These are in the book, but for Persico the real story of the war is told by those who lived it: the men in the trenches.... It is a story worth reading.

BookPage

Highly recommended... The intimate portrayal of men striving not to be the last killed enlivens this important addition to the vast literature on World War I. Readers will be captivated by the dramatic depiction of combat and life in the trenches and intrigued by Persicos concise historical analysis of events leading to the war, its key battles, and the political-military decision-making that dragged out the combat to the final bloody minute.

Library Journal (starred review)

The books full account of the war, from its causes to its conclusion, is crisp and vivid.... Where Persico excels is in reconstructing the moment-by-moment journeys of men facing possible death or mutilation, many of whom were dehumanized in the process. You can see, feel and smell these doughboys, poilus, Tommies and boschesand sense their rage and despair.

New York Daily News

An eye-opening study of the final hours of a war that threatened never to end... [Persico] ably encapsulates the whole conflict in a highly readable narrative. First-rate, and evocative of why the war to end all wars was anything but.

Kirkus Reviews (starred review)

INTRODUCTION

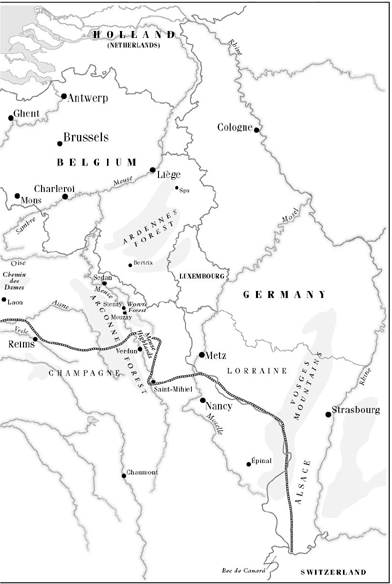

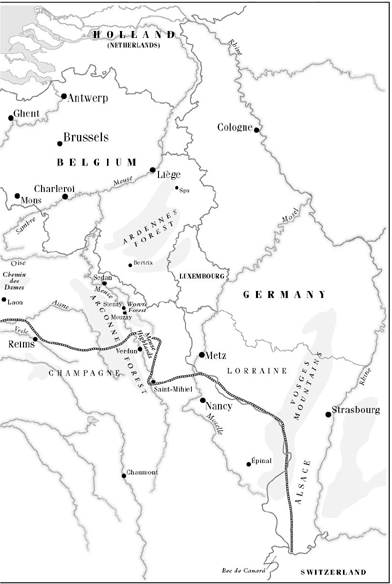

In the fall of 1919, Alvan T. Fuller, a second-term Republican congressman from Massachusettss Ninth District, received a letter from a constituent, George K. Livermore, one of an accumulating file. Grieving families wanted to know why a son, husband, father, or brother had died on the last day of the Great War when it had been known well in advance, down to the exact moment, that the fighting would end on the eleventh month, eleventh day, eleventh hour. Congressman Fuller, son of a Civil War veteran and raised on tales of soldierly sacrifice, was particularly moved by Livermores description of a plot of land outside a French village, Pont--Mousson, where he had seen little crosses over the graves of the lads who died a useless death on that November morning.

So numerous were such inquiries that in January 1920, Congress began an investigation into the conduct of leaders of the American Expeditionary Forces, beginning with General John J. Pershing, to find out why so many lives had been sacrificed after peace was assured. Casualties that last day were not confined to American forces. Large numbers of French, British, and German soldiers as well died in the final hours, even minutes.

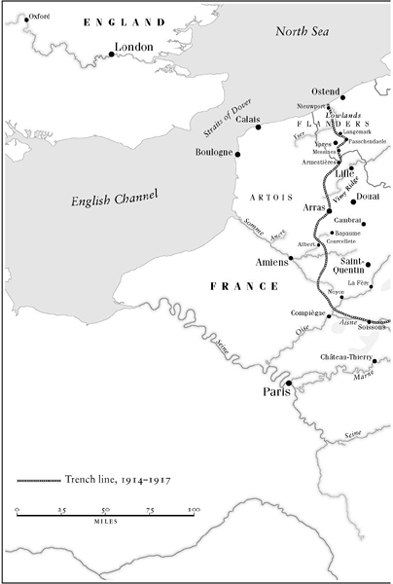

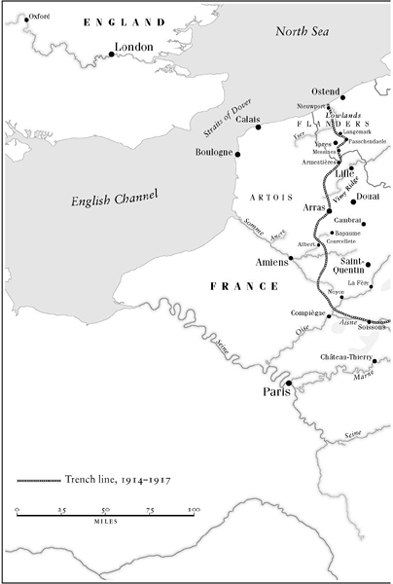

My purpose here is not to offer still another history of the war, though I follow its progression from 1914 to 1918. I am also impatient with presentations of mankinds most violent behavior as if it were a map exercise, with Jones rolling up Smiths flank while the 104th supports a strategic withdrawal by the 105th. And while the role of field marshals and generals is necessarily portrayed, the true protagonists of this story are the men in the trenches for whom what in the map rooms looked like a chess match became transmuted into titanic violations of flesh and blood. The reason I have written an account anchored to the last day of World War I is that the carnage that went on up to the final minute so perfectly captures the essential futility of the entire war. The mayhem of the last day was no different from what had been going on for the previous 1,560 days.

The story is drawn heavily from letters, diaries, and journals of participants, which explains the occasional use of such phrases as He thought, He imagined, She believed. Critics of narrative history understandably question an authors presumption to enter other peoples minds. When these phrases are used in this work it is because the people cited wrote that this is what they thought, imagined, or believed.

The Great War, as it was initially known, was indeed global, involving twenty countries on five continents. Yet today, among most Americans, the war is only vaguely recalled, a misty promontory obscured by a war that preceded it and one that followed it, the Civil War and World War II. In surviving images it has something to do with poppies, ghostly figures in gas masks, a rousing tune, Over There, President Wilsons Fourteen Points, and a fading photograph in an album of an unbelievably young grandfather or great-grandfather wearing a doughboys tin helmet and a collar that appears to be choking him. Yet, while partially hidden, the Great War still exercises a grip on the imagination. It is futile to argue that one conflict is more horrific than another. The imperative of war is to kill, and thus all wars are exercises in sanctioned murder. For the victim, it is small satisfaction whether he died gassed in the trenches, shot out of the sky in a World War II raid over Berlin, or run through by a Spartans sword at Thermopylae. Dead is dead. But the First World Wars bleak distinction is that it took opposing armies to the outermost limits of mans inhumanity to man, as any honest account of Ypres, the Somme, or Verdun will attest. Of 55 million men mobilized worldwide, nearly 9 million were lost during this war, and far greater numbers were maimed, crippled, and disfigured for life.

Next page