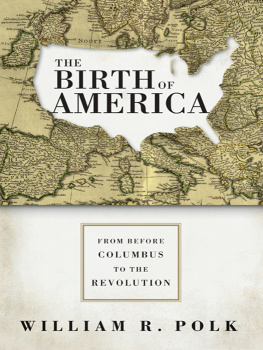

FOR MORE THAN A CENTURY, INSURGENCY HAS BEEN A FOCAL POINT in foreign affairs; its principal tacticsterrorism and guerrilla warfarehave been employed from Indonesia to Ireland and from Colombia to China. People of all races, cultures, climates, economies, religions, and languages have engaged in it. Since it is so widespread, and so costly and painful for all its participants, we must ask why it is so prevalent.

We should begin by noting what is common to all insurgencies. No matter how they differ in form, duration, and intensity, a single thread runs through them all: opposition to foreigners. This propensity to protect the home community arises because all human beings are territorial. Among primitive peoples territoriality is immediate and physical. It is usually expressed by a kin group or clan living together in a defined area small enough that the members are in daily contact. Anthropologists have found that such groups seldom exceed a hundred individuals. They are people who know one another intimately, live side by side, hunt or herd together, and often own their property in common. They are bonded by the absolute imperative to protect the resources that sustain their lives. Today such groups are rare, but the way they live is how all our ancestors lived for millions of years, conditioned over millennia to turn inward to rally support and outward to repel intruders.

As people settled down, first to become farmers, then townsmen, and finally to amalgamate into nations and even larger agglomerations, as most living people have done, territoriality has become more abstract, so that people who are not bound together by kinship may identify with one another without close physical contact as fellow members of an emotional, ideological, religious, or cultural neighborhood.

Thus, at one extreme, the operative society is a single clan; at the other, millions of people may form a nation or ethnic or religious group that takes on some of the sense of cohesion so evident in a small kin group. Regardless of size or definition, however, the society is the touchstone of individual identity. Consequently, while members may accept outsiders as guests or guest workers and even on occasion allow them to join, they rarely and usually only temporarily are willing to accept foreigners as rulers. The very presence of foreigners, indeed, stimulates the sense first of apartness and ultimately of group cohesion. This is a process that is partly automatic but is often fostered both by native leaders and by the actions of their foreign enemies. Natives tend to react violently if they perceive that foreigners are changing or corrupting their way of life, while the imperial or colonial government seeks to suppress their rebelliousness. In the action and reaction, what I have called the climate of insurgency is created. As each loses legitimacy in the eyes of the other, both employ violence. The government uses force to attempt to overawe native opponents, to create stability, and to prevent lawlessness. For the natives, who cannot otherwise convince the foreigners to leave, insurgency becomes the politics of last resort.

Is insurgency really that consistent? No, obviously there is considerable variation. In the following chapters, I will show how different cultures, ideologies, and degrees of political consciousness among insurgentsand also among their foreigner overlordshave shaped the nature of struggles all over the world during the last three centuries. But from this analytical history will emerge, I argue, that they do so without altering the fundamental motivation of violent politics. That motivation and the course of action to which it gives rise aim primarily to protect the integrity of the native group from foreigners. That the heart of insurgency is essentially anti-foreign is the central thesis of this book.

I believe authors owe their readers an account of how they arrived at their analysis. Here is mine.

From the summer of 1961, when I became a member of the Policy Planning Council of the U.S. Department of State, I was given access to the full range of information flowing into the government. My first assignment that would eventually influence this book was to head the interdepartmental task force monitoring and preparing to deal with the Algerian guerrilla war against the French. I will describe what I then learned in Chapter Eight. Algeria was an eye-opener, but even before entering government service, I had already observed, sometimes quite closely, several guerrilla wars. So it was natural that I paid particular attention to the growing conflict in Vietnam.

In Algeria, America played a minor and peripheral role, but in Vietnam, the State Department, Agency for International Development, Central Intelligence Agency, Department of Defense, and the separate armed services, as well as journalists and nongovernmental organizations, began to accumulate enormous collections of facts. No country was ever so reported upon as was Vietnam by Americans. From 1962, shortly before the major escalation of American activities began, I spent part of each day perusing the deluge of cables, intelligence reports, and summaries that poured across my desk on Vietnam. Of these a small fraction subsequently ended up in The Pentagon Papers .

In all the mass of materials, thousands upon thousands of pages, however, one looked in vain for a satisfying definition, much less a coherent and penetrating analysis, of guerrilla warfare. Everything I came across was episodic, without historical depth, short on questions but quick with answers that often seemed unrelated to events. As the months passed, I came to believe that our lack of any evident means to make sense of the daily events was so dangerousalready we were fairly deep into Vietnam and obviously were headed deeperthat I took six weeks off from my regular tasks at the Policy Planning Council and read everything I could find on insurgency.

Learning about my study, the National War College invited me to summarize my findings for its graduating class of the best and brightestarmy, air force, and marine colonels and navy captainswho were headed for senior command. I was delighted, as the occasion would force me to try out what I had learned on a very critical audience, one preparing for combat in Vietnam. Before them, I then argued that guerrilla warfare was composed of three elementspolitics, administration, and combat. I had concluded that combat was the least important element in the struggle. I told the audience that we had already lost the political issueHo Chi Minh had become the embodiment of Vietnamese nationalism. That, I suggested, was about 80 percent of the total struggle. Moreover, the Viet Minh or Viet Cong, as we had come to call them, had also so disrupted the administration of South Vietnam, killing large numbers of its officials, that it had ceased to be able to perform even basic functions. That, I guessed, amounted to an additional 15 percent of the struggle. So, with only 5 percent at stake, we were holding the short end of the lever. And because of the appalling corruption of South Vietnamese government, as I had a chance to observe firsthand, even that lever was in danger of breaking. I warned the officers that the war was already lost.